-- This article originally appeared on Todd Litman's blog at Planetizen, and was reprinted with permission of the author.

What do transportation system users consider to be the most important problem? Here’s a hint: it’s not traffic congestion.

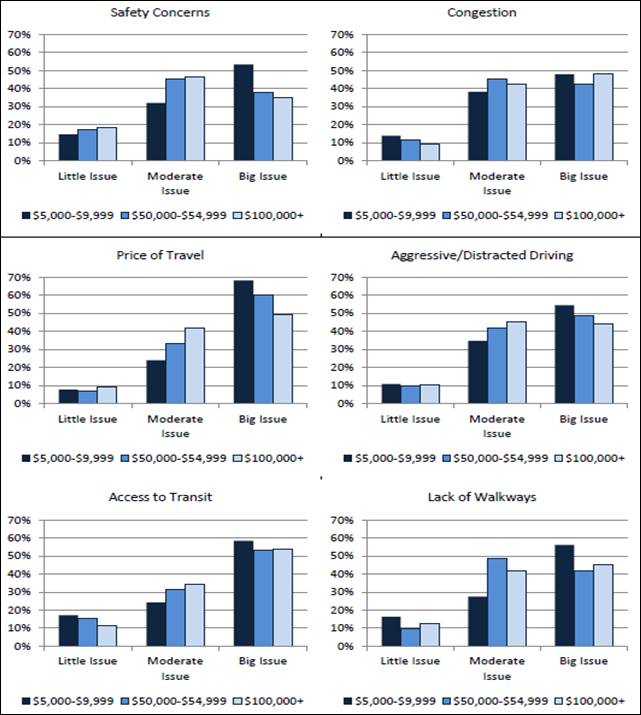

The 2009 National Household Travel Survey asked respondents to rate the importance of six transport problems: traffic safety, congestion, price of travel, availability of public transit, and lack of walkways or sidewalks. Virtually every demographic group rated affordability (“price of travel”) most important, as indicated in the graphs below.

2009 National Household Travel Survey

Affordable transport is important, particularly for lower-income people. Increased affordability is equivalent to an increase in income.

Yet, conventional planning ignores this concern. Affordability is seldom recognizes as a transportation planning objective, and if it is, it is usually evaluated based simply on fuel costs. Conventional planning ignores vehicle ownership and parking facility costs, which are much larger than fuel costs, and so ignores the inaffordability caused by automobile dependency and the user savings that can result from increased transport system diversity and land use accessibility.

Conventional planning assumes that faster modes are more important than slower modes, and that congestion reduction is the most impotant planning objective, and so favors wider roads with higher design speeds and longer block lengths over narrower, lower-speed, more connected roads. Similarly, conventional planning assumes that it is desirable to require generous parking supply at new developments which stimulates sprawl and reduces housing affordability. These planning decisions create automobile-dependent communities hostile to affordable modes: walking, cycling and public transport.

Affordability should be evaluated relative to household incomes or budgets. Many experts recommend that households spend less than 20% of their budgets on transport and less than 45% on combined transport and housing expenses, in recognition that households often make trade-offs between housing and transport costs, so a cheaper home is not truly affordable if it greatly increases transport costs. When measured this way, affordability tends to increase in more accessible, multi-modal neighborhoods.

On average, U.S. households spend 18% of their budgets directly to transportation (not including indirect costs, such as the portion of housing costs devoted to residential parking or general taxes devoted to roads), 20-40% more than other wealthy countries, and residents of transit-oriented communities typically spend 40-60% less on transportation than residents of sprawled communities.

Household Expenditures Devoted To Transport

Residents of more transit-oriented U.S. cities spend a smaller portion of their household budgets on transportation

It is not only planners who must change our approach. Many people, including well-intended anti-poverty advocates, mistakenly support policies that contribute to automobile dependency with the hope of making driving more affordable. They oppose fuel tax increases and road tolls, and support parking subsidies, although these ultimately harm poor people by increasing other taxes and housing costs, stimulating sprawl, and reducing affordable transport options. For example, a study by Lisa Schweitzer and Brian Taylor found that financing urban highways with general taxes is regressive compared with road tolls because virtually all low-income households pay general taxes and only a few drive on major highways during peak periods. Road tolls and fuel taxes can be progressive overall if revenues help finance affordable transport options (walking, cycling and public transit improvements), which helps lower-income households save money and transfers wealth from higher-income to lower-income households.

I can report from personal experience that affordable transportation is possible and beneficial, but requires an appropriate planning. Our demographically average household (two parents, two children, dog and cat) owned just one car, and five years ago when its engine failed we became car-free. We now rely on a combination of walking, cycling, public transport, taxi, delivery services and occasional vehicle rentals. We spend less than $2,000 annually on local transport, saving at least $5,000 compared with peer households. These savings finance our children’s university educations, and using affordable modes provide other benefits including increased personal fitness and more positive interactions with neighbors. These savings and benefits are possible because we live in a compact community that has good walking and cycling conditions, good public transit and taxi services, and local stores that offer delivery services.

How can planning increase affordability? Here are specific recommendations:

- Recognize transportation affordability as a planning goal of equal or greater importance than congestion reduction.

- Evaluate ways that common planning decisions (roadway expansion, parking requirements in zoning codes, the location of public facilities such as schools) affect transport and housing affordability.

- Support affordable modes (walking, cycling and public transit), for example, by applying complete streets policies which insure that roadways accommodate diverse modes, users and uses.

- Support carsharing, which reduces the need to own a vehicle for occasional use, and distance-based vehicle insurance and registration fees, which give motorists a new opportunity to save money if they minimize their annual vehicle travel.

- Support smart growth (compact, mixed, multi-modal development) and transit-oriented development which reduce the distances that people must travel to reach services and activities, and improves their travel options.

- Reduce or eliminate parking requirements, and encourage parking unbundling (parking is rented separately from building space), particularly for lower-priced housing, so residents are not forced to pay for parking they do not need.

- Encourage stores to offer delivery services.