In 2006, 14-year old Kristen Bowen was killed on the train tracks near her house in the Chicago suburb of Villa Park. She was using a well-worn shortcut across the tracks that cut her residential neighborhood off from the school and the park they used. Four years after Kristen's death, her twin sister committed suicide by stepping in front of a train near where Kristen was struck. Those tracks are covered with balloon memorials and crosses, commemorating those who have died.

The Federal Railroad Administration estimates that 500 people die every year walking on railroad tracks [PDF]. But who bears the responsibility of preventing these deaths? Was it Kristen’s responsibility to avoid trespassing where freight trains roar past? Her town's responsibility to erect a fence before being spurred on by her death? Should planners have recognized that it's human nature for people to take a calculated risk to reach the amenities they used? Or was it the railroads' responsibility to identify where these deaths happen and try to mitigate the risk?

A recent series by reporter Todd Frankel at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch makes clear that the responsibility is shared. But he also points a finger at the railroads, which have been obstructionist as others try to address the issue:

A few years ago, when the [Federal Railroad Administration] tried to get a better sense of who was walking on the tracks — by looking at trespassing cases that didn’t end in a casualty — regulators asked the railroads for help. They wanted the railroads’ internal trespassing reports. The railroads refused.

The agency recently was forced to concede defeat, noting that it “failed to garner the necessary support from the rail industry to conduct the study.”

Then there was the issue of where the casualties occurred.

For years, the agency required railroads to report only the county of a trespassing death or injury. Not the city. Not the closest milepost on the railroad system. Having so few details made it hard to identify hot spots for trespassing, said Ron Ries, director of the agency’s Highway-Rail Grade Crossing Safety and Trespass Prevention Division.

We reported in the spring that FRA guidance on pedestrian safety at railroad tracks focused only on approved crossings, ignoring the risks of so-called "trespassing" that occurs outside of those areas.

Only in the last year did federal law require railroads to provide GPS coordinates of the crashes. Before that, their crash reports only listed the county where the crash happened, making it impossible to identify where these crashes are clustered. Now, with better information, some danger “hotspots” became apparent.

Of course, neighborhoods who mourn death after death on nearby tracks already know they're hotspots. In those cases, these tragedies are often predictable, as tracks cut communities off from the services they rely on.

One of those hotspots is in Hyattsville, Maryland, a nearby suburb of Washington, DC, where four people were killed on train tracks in three years.

In an interview with Streetsblog, Frankel of the Post-Dispatch said Hyattsville perfectly fits the profile of a likely hotspot for pedestrian deaths on railroad tracks: “It’s a residential neighborhood, high density, the speed limit on [the train tracks] is 70 miles per hour, you have both freight and commuter rail,” Frankel said. “And you have residential on one side, commercial on the other, so people have reasons to be going back and forth.”

He said that when he visited the site, there were obvious paths of well-worn gravel across the track, but the railroads still claim it’s impossible to know what spots are popular pedestrian crossings. Frankel said that tracks that carry fast trains have to be inspected twice a week by a slow-moving truck. Those trucks clearly see the “deer trails” worn by many feet.

In Villa Park, he said, where Kristen Bowen died, it felt like a train went by every ten minutes. The frequency of train traffic is another risk factor. And he says passenger trains are more dangerous than freight, “because the trains tend to be smaller, lighter, and faster. Quieter.” Many of these cases involved commuter rail and inter-city Amtrak trains.

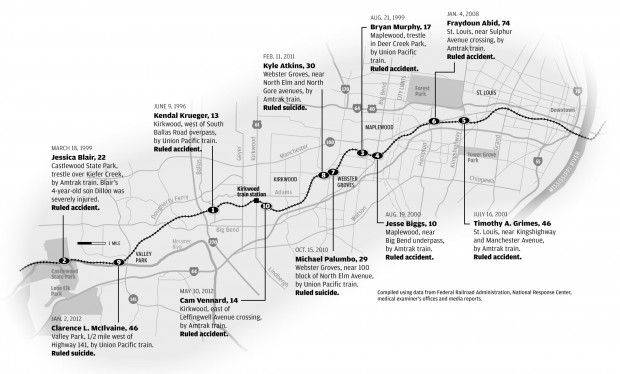

Amtrak has vigorously opposed taking more responsibility to reduce collisions with pedestrians. The agency has flat-out said that its reason for opposing a requirement for GPS reporting of collisions was that “the accumulation of such data could potentially lead to the improper assumption that railroads have a duty toward trespassers.” While the freights complained about the potential inaccuracy of GPS locating, Amtrak just got straight to the point: Pedestrian deaths – even of people like 10-year-old Jesse Biggs or young mother Jessica Blair, both killed by Amtrak trains near St. Louis – were not their problem.

Communities often look to enforcement and barriers as the solution. They can put up fencing, like major highways usually have. They can arrest people who cross. Some demand that the railroads implement education campaigns about the danger of crossing the tracks – but the fact is, most people know that it’s risky. And every day they calculate that the risk is remote enough, and the alternate routes inconvenient enough, that they’ll roll the dice.

Barriers and education campaigns ordering people off the tracks don’t address the major problem these railroad tracks present for the mobility of people walking and bicycling. Jesse Biggs could have ridden his bicycle through a short tunnel that passes underneath the tracks, but “the sidewalk there is narrow, the vehicle traffic close and fast,” wrote Frankel. Maybe Jesse Biggs would still be alive if city planners in his town had prioritized pedestrian and bicycle connectivity. Frankel writes:

The problem is the tracks run past a large apartment complex and houses on one side, with more houses, shops and a MetroLink station on the other,” he wrote. “The nearest [automobile] crossing is almost a quarter mile away. People just walk over the rails instead. “They come and go all the time,” [Sgt. Michael Martin, who helped investigate Jesse’s death] said.

In Hyattsville, where so many people have been killed crossing the tracks, residents say walking the tracks is common: “The tracks were like a highway for walking,” said Andrew Farrington, the friend of one man who died there.

Frankel says improvements at crossings where automobile traffic meets railroad tracks have been “a public safety success story,” with motorist deaths down 80 percent since the 1980s. He says about $220 million in state and federal funding is spent annually on lights and gates at crossings. But they won’t even address pedestrian safety concerns in the places like Villa Park and Hyattsville, where deaths on the tracks have become unnervingly common. Some railroads have even fought efforts to compel them to sound a warning or whistle as they approach train bridges and populated areas -- a simple measure proven to save lives.