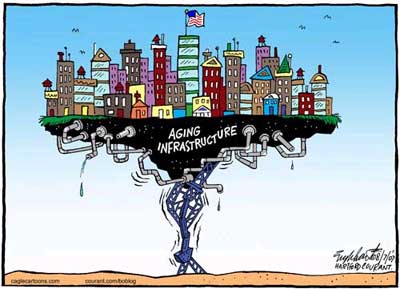

In these days of stagnant gas taxes, state and local governments are scrambling for new ways to finance infrastructure. Rahm Emanuel has his $7 billion Chicago Infrastructure Trust, and Antonio Villaraigosa has his America Fast Forward. Even John Kasich in Ohio is trying to sell advertising at rest stops to shore up ODOT.

In a new report, the Brookings Institution offers another potential answer: state infrastructure banks. These financing agencies offer local governments low-interest loans for important infrastructure projects, and they can attract additional private capital.

“With Washington gridlocked and retrenching, the new state banking models offer a hopeful counterpoint to national dysfunction,” said Brookings' Mark Muro in a press release.

State infrastructure banks aren't a new tool. The first ones were created with an infusion of federal cash in the early 1990s. Today, 33 states have an infrastructure bank or a state revolving fund. These institutions have financed about $9 billion in infrastructure spending for 1,200 projects. About 88 percent of the total spending, however, went to road projects.

Republicans wanted to include federal funding to recapitalize SIBs in the transportation reauthorization, but MAP-21 did not offer any changes to the way these institutions are structured. The bill didn't include a national infrastructure bank either, which Republicans oppose.

Robert Puentes, director of Brookings' Metropolitan Infrastructure Initiative, emphasized that while SIBs can address some funding problems, they are no substitute for a national infrastructure bank. SIBs can be inappropriate funding mechanisms for projects of truly national significance or that cross state lines.

"They are similar in name only, " Puentes said. "They would fulfill very different functions."

Indeed, SIBs vary greatly in their effectiveness. Of the existing 33 SIBs, 10 are inactive. The major factors that determine success, according to Brookings, are pretty simple: The SIBs must have sufficient capital, and they have to apply market discipline when selecting projects, prioritizing those that offer multiple benefits and strong economic returns.

Many times, however, the most competitive projects are toll roads. It's often hard for transit to compete when the overriding interest is in direct return on investment from users, rather than public benefit.