Attacks on transit drivers are not a new problem. But it seems to be getting worse.

A bus driver now gets assaulted every three days in the United States, estimates the Amalgated Transit Union. Headlines abound of drivers getting kicked, punched, stabbed and shot, while the lower-profile offenses – spitting and verbal harassment – have almost become part of the job description.

For many transit workers, it’s plain to see how the recession has inflated a trend that already existed. Working alone and dealing with money, drivers have always been vulnerable. Mix in a more frustrated, downtrodden population of passengers with a host of service cuts and fare increases, and you get combustion.

“People who are poorer than they were, … who rely more on transit than they did, who are waiting longer at bus stops for the bus to come because the service has been cut,” said Larry Hanley, president of the ATU. When they board the bus, “the driver’s sitting there in a uniform, representing the government, telling them, you got to pay a higher tax for this service,” he said.

Nationwide statistics are lacking, but many jurisdictions have reported recent increases in driver attacks. The Philadelphia Transport Workers Union local reports that assaults there more than doubled in 2011 compared to 2010. New York City has seen a 30 percent increase in 2012. There’s also not a lot of hard data linking an uptick in assaults to fare increases or service cuts, said Robin Gillespie, program director of safety and health at the Transportation Learning Center. But “people feel that way,” she said.

And attacks occur most commonly during fare collection. “The conflict is over money,” said Hanley. “It’s people who have a pocket full of empty and have to get to a place.”

As the problem gets more prevalent, transit unions are getting more organized in their efforts to deal with it.

This spring the ATU teamed up with the TWU to form a new coalition focused on driver safety issues.

“It’s a nationwide project to look at what’s going on with transit operators,” said Gillespie, “a national campaign that’s organized by the international unions… with support from transit agency groups.”

And last month, TWU Local 100 helped organize what was thought to be the first national conference on transit worker assaults. The May 10 event in Brooklyn was New York City-focused – with various local officials attending – but helped fuel a broader conversation, said John Johnson Jr., president of TWU Local 234 in Philadelphia.

Johnson came to conference sharing personal experience – as a driver, he once had a gun put to his head – as well as wisdom from his union’s recent activism.

Following a marked increase in attacks in Philadelphia, TWU Local 234 organized a task force to work with city officials and community groups, and took a survey of local bus drivers. In the report Johnson sent to Streetsblog [PDF], 40 percent of responding drivers said they had been victims of assaults and 64 percent had witnessed assaults.

The survey was “the first in the country” to gather information directly from drivers, according to Johnson. In the past, he said, “a lot of them mentioned they were assaulted, but they themselves haven’t reported it” to the authorities, sometimes due to fear of taking the blame.

More research on assaults as a national phenomenon is happening right now, according to Gillespie. Her organization, the Transportation Learning Center, is working with labor unions and transit agencies across the country to pull information together.

There’s also a growing national conversation about ways to fix the problem. The new union coalition has been “working to try to figure out some creative solutions so that we can actually prevent the assaults before they happen,” Hanley said.

Some of the ideas out there are fairly experimental -- like arming drivers with pepper spray or tasers. In New York City, there’s been talk of cash rewards for riders who report assaults.

A few options would require potentially expensive changes to bus designs. Many drivers have pushed for creating a door on the left side of the bus, near their seat, so they can exit that way.

And various cities have tried enclosing drivers with a physical barrier, like a Plexiglas shield. That tactic is controversial, said Jeff Rosenberg, ATU’s director of government affairs. “Some of the drivers seem to like it, others said they didn’t like the feeling of isolation,” he said. Issues like air-conditioning can complicate design.

Last December the Transit Cooperative Research Program of the Transportation Research Board put together a thorough report on different strategies for reducing assaults.

Most effective, the report found, is video surveillance, operator training and a visible police presence. The latter has seen success in Pierce County, Washington, where a uniformed fleet of officers helped reduce criminal activity by 60 percent, and in Boston, where police cars “escort” buses on high-risk routes.

The new union coalition will also be looking at legislative solutions. Though the Patriot Act allows for up to 20 years in prison for an assault of a transit worker, Rosenberg said, “the problem is, it looks good on paper but has not actually been enforced … even in some heinous cases.”

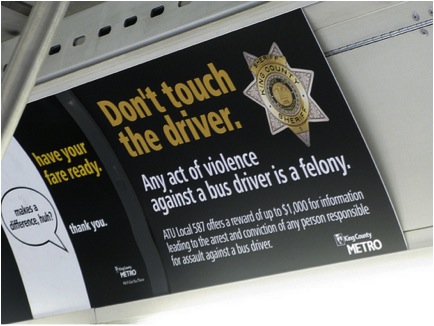

The ATU has already been active in pressing local jurisdictions to set stiffer penalties for assaults, and to advertise those penalties to the public. In states with weaker protections, “a lot of laws are rendered meaningless,” Rosenberg said, with cases never making it to court.