For many neighborhoods, a shiny new light rail line can be a blessing and a curse. Yes, it provides access to affordable transportation options that can be the avenue to jobs and economic opportunity. But it can also bring higher housing costs and drive up retail rents, exiling area residents and local businesses.

And so sometimes, vulnerable communities oppose the introduction of new transit opportunities, even if they would benefit from more frequent and reliable transit service.

As Jeremie Greer of DC’s Local Initiatives Support Corporation said at Rail~Volution last week, building broad support for new community services is essential. “If everyone feels like they’ve put forth an effort to develop a plan or vision, hopefully people will feel committed to seeing it out,” he said. “And you wont get Reverend So-and-So in the paper saying, ‘These racist people are trying to drive us out of the community.’ Because Reverend So-and-So, hopefully, was at the table expressing his vision or her vision.”

But low-income communities’ relationship to transit cuts both ways. Just as they sometimes resist new amenities they fear will raise rents out of their reach, they're also often on the front lines of the fight for better transit access.

The “Stops for Us” campaign in the Twin Cities provides a model example of a successful, neighborhood-led effort to ensure equitable transportation access and spark a change in federal policy.

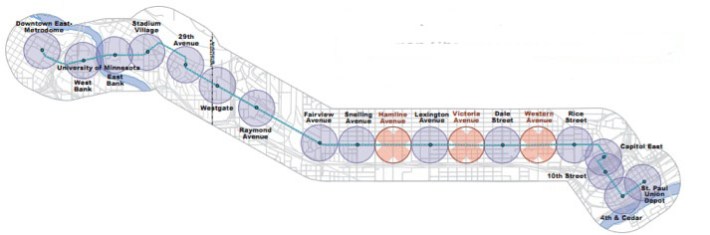

It all started in 2006, when the Central Corridor Light Rail Transit stations were announced. The 11-mile line, connecting the downtown districts of Minneapolis and St. Paul, had gaping holes in the neighborhoods with the greatest poverty, biggest minority populations, and most car-free households. While the stations in St. Paul (17 percent poverty rate, 36 percent minority) were spaced just a half-mile apart, in the Frogtown neighborhood (35 percent poverty, 73 percent minority) the distance stretched to a mile between stops.

“From the community’s perspective, the line had to benefit everyone,” said Carol Swenson, Executive Director of the District Councils Collaborative of Saint Paul and Minneapolis. “Transit is an important piece of daily life of the community on the eastern end of University Avenue… Ridership on the route 16 bus is highest in the region, so this would be a high-use corridor and with a lot of riders using the LRT.”

The station disparity sparked the “Stops for Us” campaign, an effort led by more than a dozen community groups, like the St. Paul Urban League and the local Asian Economic Development Association. “We started to go out into the community with maps, asking people, ‘Where should the stations be?’” Swenson said. “Most of the dots were showing up in places the stations were not.”

Many residents along the corridor -- particularly in the neighborhood around what used to be Rondo -- had already experienced the devastating impact of poorly conceived transportation projects. In the 1960s, construction of Interstate 94 plowed through Rondo, splitting the predominantly African American community in half and displacing more than 70 businesses and 400 families. Adamant that history not repeat itself, members of Preserve and Benefit Historic Rondo played a leading role in the campaign for inclusion in the light rail plans.

The Stops for Us coalition didn’t just ask that policymakers to do what was fair — they showed them the data. “We initiated a research project in the summer of 2007 that looked at station spacing nationally and the implications for our line locally,” said Swenson. The study showed that, around the country, transit stops in urban areas were less than a half-mile apart, on average. They supplied information about key destinations along the Central Corridor and their distance from the proposed stations, and noted that extreme weather in the Twin Cities reduces the distance people should be expected to walk to transit.

The coalition put forward a proposal for three additional stations that filled in the gaps. With their detailed maps and clear demands, they got involved in the planning process, providing input during the federal project review.

The regional planning agency insisted that the original station spacing was necessary to keep the project on time and on budget. Additionally, if the cities wanted to tap into funding from the Federal Transit Administration, they had to make sure the project passed the FTA’s Cost Effectiveness Index (CEI), a measure of the cost of the system divided by user benefit. Adding the three stations along eastern University Avenue would sink the CEI and make the project ineligible for critical funds.

What finally tipped the scales, Swenson said, was the Rail~Volution conference in 2009. She called the event a “game changer.”

“We had the opportunity to approach [FTA] Administrator Peter Rogoff and asked, would he come and talk to us on our own ground and hear us out,” Swenson said. “Much to his credit, that’s what he did.”

When Rogoff visited, the coalition explained how the CEI represented a major roadblock for community equity. Rogoff clearly listened. “Two weeks after he walked out of a meeting with us, with all our maps, and went back to Washington, the CEI was changed and the funding came together,” Swenson said. “We got our stations.”

In January 2010, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood headlined the press conference announcing the addition of the Victoria, Hamlin and Western stops on the LRT. But the impact went far beyond the Central Corridor in the Twin Cities. The change in policy meant the CEI wouldn’t make or break a project in qualifying for funding from the FTA's New Starts and Small Starts programs. Projects that fared well in other categories — like economic development, land use, environmental impact and mobility improvements — could also earn federal funding.

Still, the inclusion of the three new stations was just the first — and possibly easier — step for the coalition members. Now, Swenson says, those same groups are working to ensure that, once the stations are built, the transit line doesn’t have a negative impact on the communities that fought so hard for inclusion.