I promised in my last post to tell you the triumphant stories of citizens beating back highways, both planned and already built. Here are more stories from the Rail~volution bike tour around Portland's "lost highways."

Exhibit A: The Mount Hood Freeway

“There was a period of ignorance, a period of enlightenment and catharsis, and a period of change.”

Longtime local planning official Dick Feeney says Portlanders shouldn’t be too smug about their much-touted bicycle network and strides on transit. After all, he says, “Portland founded the Good Roads movement,” which had its basis in the gas tax. “And the gas tax became this monumental engine to give a private subsidy to the private automobile. It started right here, folks… part of our own destruction started right here.”

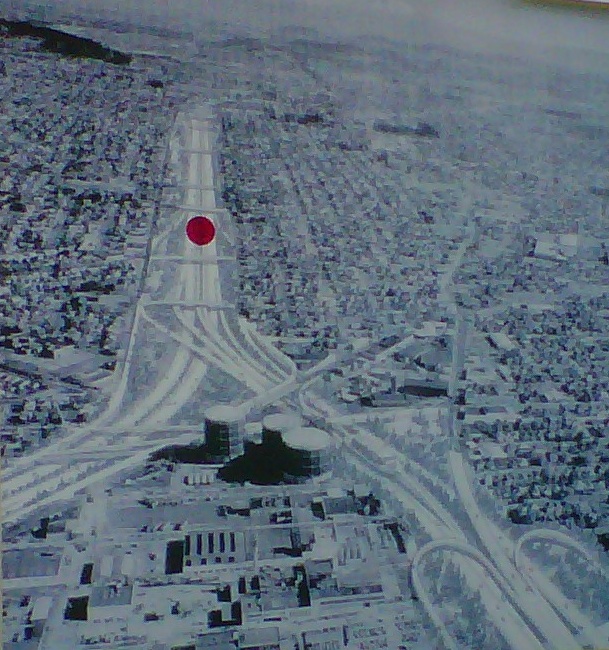

The Mount Hood Freeway was almost part of that destruction. Proposed by the Oregon State Highway Department in 1955, the road would have been eight lanes wide and removed one percent of all the private housing stock in the city. An estimated 3,700 children would have had to cross it to get to school.

In the 1960s, the city of Portland set about buying up houses they’d need to demolish to build the freeway – including the home next door to State Rep. Grace Peck, who wanted her neighbor’s house torn down early “to keep hippies from living there,” according to Richard Ross, former head of planning for the Portland suburb of Gresham.

Before long, the freeways became the polarizing issue in Portland, on which every aspiring politician had to take a position, firmly in one camp or another. Unions wanted highway construction to provide jobs. Environmentalists and farmers sided against it. Finally, popular opposition to the project reached the point where the city and county withdrew support, and the project died.

Exhibit B: Harbor Drive

Okay, Portland, you can get a little smug about Harbor Drive.

Portland was the first major city to rip out an existing highway, and it couldn’t have happened to a nicer stretch of land. Harbor Drive ran along the western shore of the Willamette River in downtown. In 1968, as I-405 was being built, Governor Tom McCall appointed a task force to study the possibility of tearing out Harbor Drive and making it a park.

Urban planner Ernie Munch advocated for the teardown:

The committee went on and on and on and on until 1973 or 1974, when Tom McCall and Glenn Jackson, who was the head of the highway division, were going over that ramp onto the Markham Bridge, and they looked down on this area and they said, “Let’s just do it. Let’s just take it out.” So in 1974, Harbor Drive was removed. It was, at the time, the city’s busiest arterial. One-third of the traffic went to the freeways on either side of the downtown. One-third went in to the downtown. And one-third has never been heard of since.

What happened to those cars? Where did they go? It's hard to say precisely, but the example of Harbor Drive stands as a good reminder that the amount people drive rises and falls with car capacity -- and infinitely expanding roads won't keep them clear of traffic jams.

It's important to note that it wasn’t just one good man in power that made Harbor Drive the waterfront park that it is today. A whole citizens' movement mobilized in support of the teardown plan. In the summer of 1969, Portlanders even organized “consciousness-raising picnics” along Harbor Drive.