This week on the podcast, we’re joined by Benjamin Schneider to talk about his book, The Unfinished Metropolis: Igniting the City-Building Revolution. Schneider, a rising star in the urbanism movement, chats about the "unfinishedness" of cities, the larger origins of NIMBYism, and how much our economy and built environment cater to cars.

Also worth noting: We ran an excerpt from Schneider's book on Streetsblog NYC last month. Check it out here.

As you know, Talking Headways gives you three — count 'em, three — ways to enjoy the content. First, you could read our full unedited transcript, generated by AI and likely filled with minor typos.

Or you could click on the "play" button below and just revel in the aural experience of the podcast.

Or you could read the partial edited section that starts here:

Jeff Wood: There’s a lot of interesting stuff in the book about zoning codes and the history of that, too. And I was really interested to learn from the lower court ruling in Euclid v. Ambler Realty how zoning kind of got encased in stone.

At the time, people really expected things to change over time. The lower court ruling said people expect change, and so change is inevitable. But then Euclid v. Ambler cut that off at the pass and now we’re in this era where zoning is kind of restricting things.

So I’m wondering how you came across that and what your thoughts are on that specific item.

Benjamin Schneider: The lower court ruling in Euclid v. Ambler is what ultimately enshrined single-family zoning and zoning more broadly as the law of the land in the U.S.

But what people may not know is that before that Supreme Court decision, there was a lower court decision that actually sided with Ambler Realty and said it’s actually not acceptable for the city to zone your property just for single-family homes. And it used language to the effect that "the continued growth of the city is reasonably to be expected."

And to me that that’s such an important way of describing how urbanism was kind of understood in the popular imagination, in the legal world, throughout human history, really: that cities evolve, that they are living, growing things. And that’s what makes the Supreme Court reversal of that decision so influential. It basically said, "No, that’s not the case. Cities can and should be frozen in the state that they currently are in 1924."

And the further you get from that moment of freezing a city, the less and less that city reflects the present-day needs and wants of the people that live there.

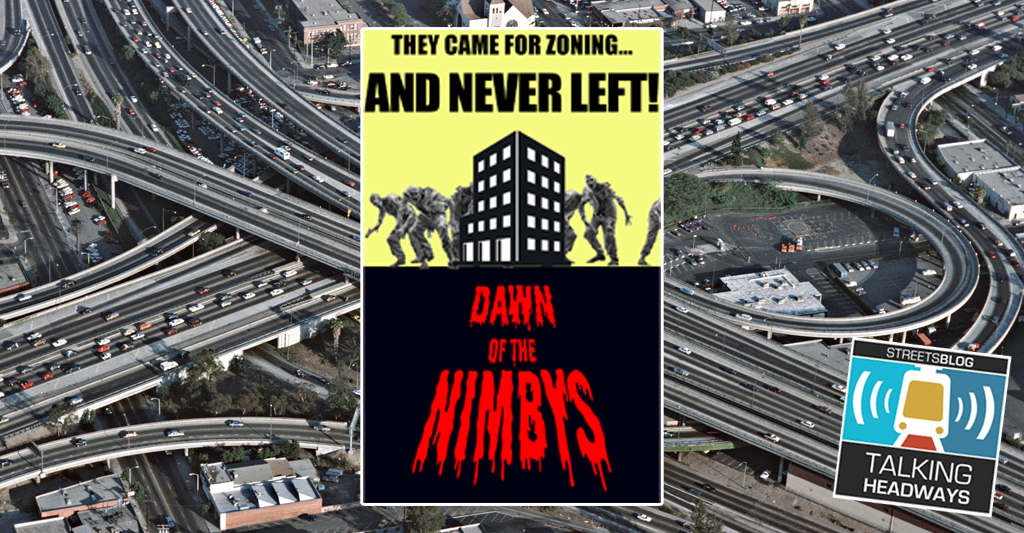

Wood: I feel like in this book you’re chronicling "the Dawn of the NIMBY." There are a lot of books out now about YIMBYs. But you have all these ideas about the light and air, the fire codes, rabble-rousing apartment-dwellers.

We’ve had NIMBYs for a long time in the United States, but this feels like the understanding of where they’re coming from.

Schneider: I’m glad you tapped into that because what I’m hoping to do with this book is not to vilify NIMBYs, but to show how NIMBYism is sort of baked into the American system — in our laws, our culture, our just sort of baseline sense of reality.

We’ve been trained to understand that the urban environments that we grew up in are basically going to remain that way for our entire life. That’s what single-family zoning did, but it’s also what car-centrism did.

You know people who were living, say, in the 1950s had witnessed these really huge transformations of transportation systems. They’d seen everyone getting around by streetcar, then they’d seen streets get completely reorganized to prioritize cars. They’d seen the emergence of freeways. And then even some more exciting developments like BART — kind of unimaginable Space Age transit technologies.

But in our time, really have only known kind of the car-centric transportation system that we have. There’s not really living memory of another way of doing things or really a frontier of new kinds of ways of getting around cities that we can be excited about and kind of project into the future.

But for the most part, we kind of live in this eternal present of cities being a certain way and always seeming to remain that way.