Black North Americans often struggle to find safety, mental health, and sense of true belonging in the public realm, a new report finds — and to tackle those hidden barriers to access, transportation professionals and the traveling public need to look beyond the realm of traditional policy and strive to become "stewards of joy" for their neighbors.

In a binational survey of more the 600 Black respondents in more than 100 cities, researchers dug into the nuances of what it means to be "Black in Public" — which eventually became the title of the report —and what it will take to achieve access to "space, joy and justice for absolutely everyone."

Initially conceived in the wake of the civil rights uprising the followed the death of George Floyd, the report from the Toronto-based Jay Pitter Placemaking quickly evolved beyond conversations about police violence against people of color, and grew to encompass both a deeper history and a deeper set of questions about our present moment.

“This maps all the way back to the auction block," said Jay Pitter, the firm's founder. "Black people have a very distinct history of un-safety and lack of mobility in the public realm, as people who first appeared in the public realm here, and across the diaspora, as individuals who were not legally deemed human beings, and who were not free by law.

"And so I thought it was really important to do work that was outside of the cycle of protest and public space violations," she continued. “I wanted to understand what Black people's broader experiences [are] in public spaces, outside of the trauma and tragedy that tend to make the media headlines. I wanted to learn about what was working — and what brought black people joy in public spaces as well.”

Pitter emphasizes that neither the challenges nor the joys of being Black in public are constrained to the transportation realm — though roads, sidewalks, transit and bike lanes are uniquely fraught.

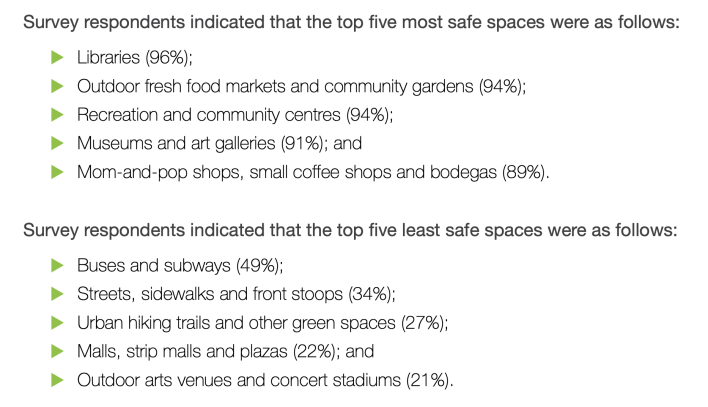

When asked to rank the public spaces where they felt least safe, 49 percent of respondents said "buses and subways," followed by streets and sidewalks (34 percent) and urban hiking trails and other green spaces (27 percent).

Pitter acknowledged that much of those experiences are shaped by law enforcement, noting stats that Black people account for up to 85 percent of police shootings in some states despite comprising just 13 percent of the U.S. population. Non-lethal forms of police harassment can make the transportation experience harrowing, too, with Black people disproportionately being stopped by police for virtually every dubious transportation "crime," including jaywalking, bicycle violations, suspected fare evasion on transit, and so many more.

That well-publicized state violence and surveillance, though, is often compounded by interpersonal surveillance from other travelers, which Pitter says is less talked about but still acutely painful. Countless respondents described the alienation of being on the receiving end of unwelcoming glances on the sidewalk, or simply being the only visibly Black person on a neighborhood road — whether or not those moments escalated to a violent confrontation with an officer.

“There was a lot of what we call ‘citizen profiling’ in this practice, which is everyday people profiling Black folks — people asking where they're going, what they're doing in particular spaces, or if they pause on corners or on streets, having that pause be perceived as loitering versus leisurely," she said. "[Respondents] talked about people not sitting beside them when they were on subways, and how that was humiliating and just overall disheartening for them."

As those experiences accumulated, many respondents felt uncomfortable expressing their "cultural swagger and perspectives" in public, especially when they feared that they would be harmed, judged, or barred from opportunities because of it. A staggering 73 percent of respondents reported "being hyper-vigilant in presenting as respectable and/or countering anti-Black stereotypes in an effort to redeem the entire Black race"; another 66 percent even confessed to "changing their speech when communicating with individuals outside of their racial or local community, in order to fit in or be listened to."

And those experiences can translate to real loss of opportunity over time. A full 37 percent of respondents said they "had missed out on an economic or educational opportunity due to [the] discomfort" of constant code-switching, self-repression, or outright avoiding situations where they didn't feel welcome to be their full selves.

Pitter was particularly shaken by one survey respondent, who found the burden of being othered so heavy that they didn't even apply to university until they were 30.

“Langston Hughes talked about dreams deferred; that's a really long time to defer a dream," she added. "And there are economic impacts from not being educated in a field that you feel passionate about, as well a psychological and a spiritual impact."

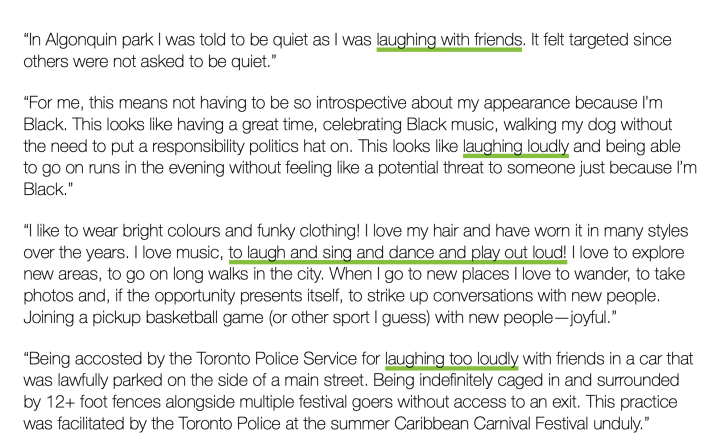

Perhaps what moved Pitter most, though, was respondents' consistent desire simply to laugh in public – and how many of them did it anyway, despite a long and very literal history of campaigns to suppress their joy. She recalls the American South's disturbing policy of forbidding enslaved people from laughing, and the invention of the "laughing barrel" — a literal barrel in which Black people could muffle their laughter out of the earshot of others – to give them a safe space to fully express themselves.

Today, an astonishing number of her respondents still report being cited, harassed, regarded with disdain, and otherwise reprimanded simply for audibly experiencing joy. And yet, Pitter marvels at how frequently they still do it — and what that says about the spirit of her community.

"Black public joy is a type of joy that even the auction block could not extinguish," she said. "Even though Black people have faced such severe and prolonged place-based oppression, we still have held on to our laughter ... Logically speaking, we shouldn't be a people who laugh in such a bold and glorious and bold and audacious way. We really shouldn't, if you think about the history. But we do."

To make public space – and in particular, the transportation space — truly accessible for Black North Americans, Pitter says policymakers need to go deeper than just pursuing police reform or ditching jaywalking laws and other policies that disproportionately harm Black and brown walkers with no tangible benefits to broader public safety.

That could look like revisiting noise and nuisance policies to stop criminalizing Black self expression. It could also mean creating "social policy agreements" for new transportation spaces that bring community members together to talk about "how that space can facilitate public joy for absolutely everyone" — and what a humane response should be if someone, for instance, is experiencing a mental health crisis on a subway. Her report also delves into a wealth of case studies about how parks and other public spaces can be redesigned to reimagine a future where Black communities can thrive.

At the end of the day, though, Pitter emphasizes that ending racism in the public realm is everyone's responsibility, not just policymakers and park designers — and transportation advocates need to step up to do their part as neighbors.

"There are some things policy really can't respond to," Pitter says. "What I love about this survey is that some of the findings point to the big, gnarly things that policy needs to address, but some of it really just points to how we're going to show up tomorrow when we go outside. For each of us to think about ourselves as being public space stewards — [because] we are actually stewarding each other's joy."