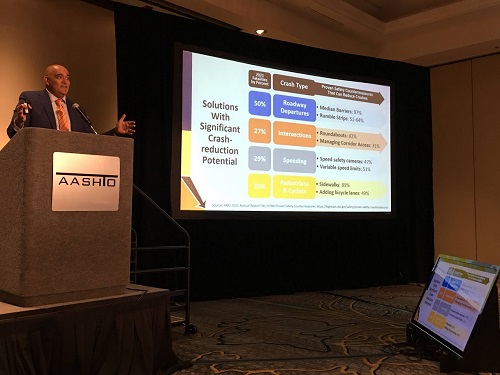

At the 2023 AASHTO Safety Summit — an event which gathers together basically all of the top state highway officials across America — then-Federal Highway Administration Administrator Shailen Bhatt passionately called on his colleagues to make one simple change to save countless lives on our roads: use more "proven safety countermeasures."

“Proactive implementation of proven safety countermeasures can move us towards zero fatalities,” said Bhatt, who left the agency this fall after nearly two years at the helm. “These are things our [division offices] can help you implement. There is so much we can do together — for it will take all of us together to solve this crisis.”

Barely known outside of wonky transportation circles, the term "proven safety countermeasures" refers to a federal list of road design elements which the U.S. DOT has encouraged states to implement widely since that list was first written in 2008. More specifically, though, these measures offer safety benefits that have been meticulously proven and quantified by U.S. DOT itself, in the hyper-specific contexts in which traffic engineers might use them — a far higher and more important bar to clear in the bureaucratic world of state DOTs.

Put another way: it's not enough for a traffic engineer to know that putting a concrete barrier between a bicyclist and a rushing river of cars will save lives, even if that's patently true. They need to know that crashes will go down an average of exactly 49 percent on four-lane, undivided collector and local roads in an urban area — and that they'll have reams of federally compiled data to point to when residents inevitably question an agency installing a bike lane on a similar road in their community.

Until it was last updated just three years ago, though, that all-important list of proven safety countermeasures didn't include some of the most basic roadway elements aimed at saving the lives of vulnerable road user, including bike lanes themselves — as well as rectangular rapid flashing beacons at crosswalks, street lighting in general, and even the very concept of setting "appropriate speed limits for all road users."

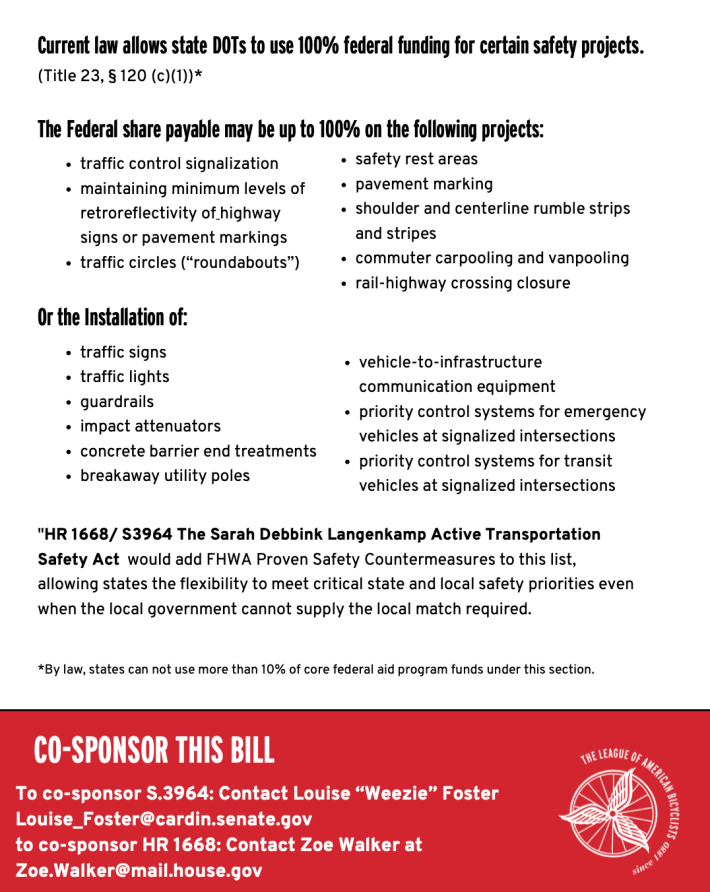

Worse, because federal law didn't explicitly include "proven safety countermeasures" for bicyclists and pedestrians under the category of safety projects which DOTs can fund entirely with federal dollars, states were forced to chip in at least 10 percent of their own money to build them. And in practice, that meant some didn't build many proven safety countermeasures at all, focusing their energies instead on stuff for which the feds would pay the whole tab, like guardrails, traffic lights, and breakaway utility poles.

"It's not like [state DOTs] can't [build proven safety countermeasures] under existing law; it's that historically, they haven't," said Ken McLeod, policy director at the League of American Bicyclists. "And so we're looking for ways to get them to do those commonsense safety countermeasures — and unfortunately, that requires a a bill in this case."

That bill is the Sarah Debbink Langenkamp Act, which will, among other key changes, allow states to build proven safety countermeasures like bike lanes using 100 percent federal money, rather than scrounging up a 10-percent local match that many cash-strapped communities can't afford.

Named for a U.S. diplomat who was killed by a truck driver while cycling in an unprotected bike lane, the bill has been gaining bipartisan momentum in recent months, amassing 75 co-sponsors in the House by the time this article was published, six of which were Republicans. Two of the bill's five co-sponsors in the Senate, meanwhile, are in the GOP, giving proponents hope that the legislation has a future as part of the next surface transportation bill, despite big changes in Washington.

"This is real progress, and I'm more optimistic than ever that we can get this bill passed in the next few years," Dan Langenkamp, Sarah's husband, told to Streetsblog. "It would make a small but important change that would permanently help states have more flexibility in using federal highway fund to build bike/ped infrastructure."

Increasing state control over how communities make their roads safer is a message that advocates hope a GOP-held Congress can get behind — especially since the bill wouldn't touch a separate federal law that prohibits states from spending more than 10 percent of their total safety money on projects for which the federal government is paying 100 percent of the cost.

Bike League Deputy Executive Director Caron Whitaker says that detail may be important to get the bill past the most conservative lawmakers, many of whom who balk at handing out any more federal money, even if it could save lives.

"One of the pushbacks we get from Republicans is they don't want things funded at 100 percent," Whitaker added. "[This bill] says, 'Only these specific projects, and only up to a certain dollar amount.'"

For states that are comfortable with — or even starving for — more federal cash for active transportation, though, the 10-percent funding bump the Langenkamp law would provide could mean the difference between a bike lane getting built or not.

And some of America's most prominent transportation leaders have already spoken out to demand it. After Bhatt's challenge to the AASHTO members to implement more safety measures, Missouri DOT Secretary Patrick McKenna and California DOT Secretary Toks Omishakin both stood up in the crowd with a message for the Administrator: make it worth our while.

"They said, 'We need incentives to do these projects,’" Whitaker said. "That's what this bill does.”

Even as America enters an uncertain new era, supporters of the Langenkamp bill say strategies like protected bike lanes are becoming increasingly normalized in the minds of American transportation officials, thanks in no small part to their status as a proven safety countermeasures. And while a few legislative tweaks might not make them a normal sight on our roads, at least it's a start.

“In the last Trump Administration, safety was one of the things that they talked about a lot when they talked about transportation policy," McLeod added. "So I hope that continues in the next administration — because we have real safety problems to address.”

Editor's note: this article has been updated to reflect additional co-sponsors of the Sarah Debbink Langenkamp Act.