Note: This article was published before the results of the 2024 presidential election were known. But it makes relevant points about campaigns, regardless of who won.

Every four years, economists come out of the woodwork to remind us of one metric that could help predict the presidential election: the national average gasoline price.

It's no wonder why: In car-dependent communities, the price that people pay to power their cars is taken as a proxy for the health of the economy itself, eclipsing a universe of other economic indicators that aren't stamped on massive roadside billboards across our communities.

Before he dropped out of the race, President Biden's approval rating plunged as gas prices rose, even though many pundits traced those increases to the Russian invasion of Ukraine rather than any of his energy policies. And since Vice President Harris joined the race, Trump has centered the pump in attack ads against her, noting that fuel costs have increased 50 percent compared to when he left office.

Though he made the prediction way back in January, economist Mark Zandi of Moody's forecasted that the Democrats would retain the White House "if gasoline falls toward $3 a gallon by election day" — which happened: AAA recorded a nationwide average of $3.10 average on Nov. 5.

None of these stories, though, seem to mention how expensive transportation would be in America even if gas were free — and how mass car dependency all but guarantees that status quo.

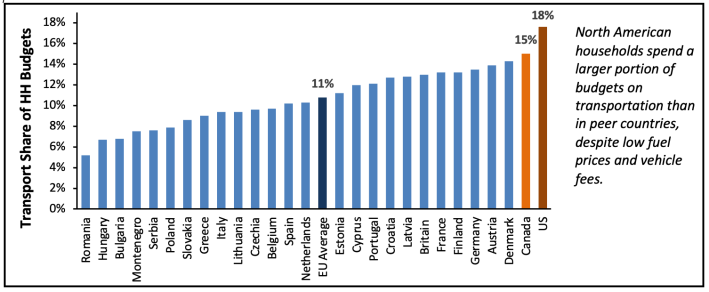

In a recent report, the Victoria Transport Policy Institute noted that U.S. households spend nearly 18 percent of their budgets on transportation alone. That's higher than the 15-percent share most personal finance experts recommend as an absolute maximum, 63.6 percent higher than the transport share of the average European's household budget, and roughly double the share spent in multimodal nations like the Netherlands, Spain and Italy. And those numbers don't even factor in the indirect costs of mass automobile ownership, like mandatory parking minimums that increase rents up to 15 percent in large cities.

The difference, researcher Todd Litman said, can be chalked up entirely to the fact that most American households are functionally forced to own and drive multiple cars, or else sacrifice their ability to work, buy groceries, and participate in society in even basic ways.

"It's not possible for most people to live a car-dependent lifestyle and not be economically stressed," he added. "They might be able to do it some years, but they’re so vulnerable to a fuel cost spike, or a crash, or a breakdown. …The clearest solution is creating a more multimodal transportation system where you don’t have to drive as much."

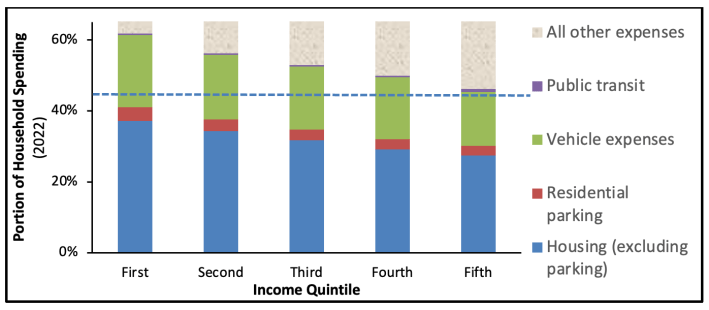

For low-income people, Litman says, compulsory car ownership can be a particularly heavy burden — and one that's not easily assuaged by cutting the gas prices that politicians drone on about.

Because many of the costs of driving are more or less fixed — think vehicle depreciation, financing, insurance, and fees over which drivers have little control — America's poorest motorists don't get much of a break even if they can cut their gas bill by driving a little bit less or finding a lower rate per gallon. Litman goes so far as to argue that "even a free vehicle is unaffordable for many low-income households" because they aren't able to maintain it, especially if anything goes wrong.

"Low-income motorists do everything they can to save money," Litman added. "They buy old, depreciated vehicles; they buy minimum insurance coverage or they drive uninsured; they try to do their own repairs if possible. But it's simply not feasible for most low-income motorists to own and operate a car and spend less than $4,000 a year."

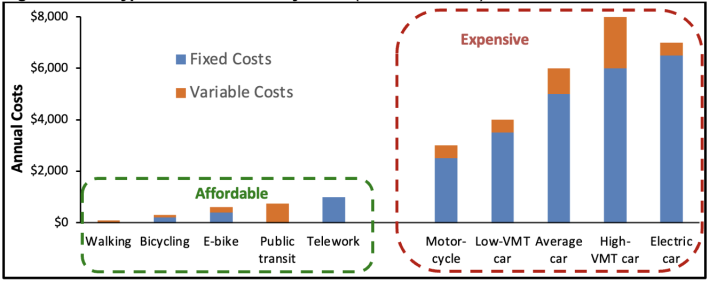

Using sustainable modes, by contrast, costs a tiny fraction of what car ownership does, both because walking, biking, and transit tend to have more variable costs over which commuters have at least some control — think skipping a short bus ride and taking a long walk instead — and because their fixed costs are so low that they're more or less a blip in the household budget, even when the occasional bike gets stolen or a metro card gets lost. Litman himself says he and his wife functionally financed his children's university education by forgoing car ownership for 15 years, and living car-light before that.

They were only able to do that, though, because they were able to find a home in a walkable, transit-rich neighborhood — and in America, those neighborhoods are in famously short supply. One 2023 report found that human-scaled communities represent just 1.2 percent of the land mass of the top 35 U.S. metros.

"Most lower-income people would say, 'Yeah, I just want cheaper driving' — but on the other hand, [surveys] clearly show that more than half of all households in the U.S. would also prefer to live in a neighborhood where you don’t have to drive as much," Litman added. "And I think a big part of the reason that people say that is because people who live in those neighborhoods are saving a lot of money. "

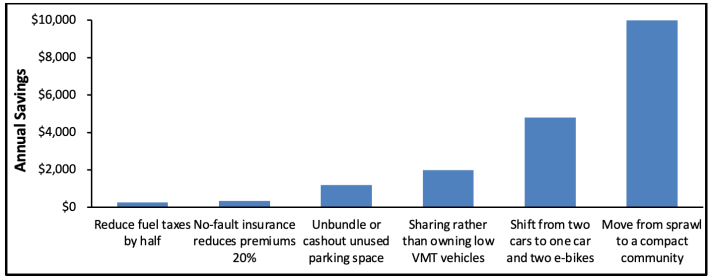

Litman says that by far the most effective strategies to bring down a household's transportation costs involve reducing how many cars it owns and how much its members drive the ones they have — at least if they live in places where those choices are feasible. In many U.S. communities, they're plainly not, so it's the responsibility of policymakers to prioritize making car-light living a real option for more people. This can be accomplished through policies that encourage building more housing and services in multimodal communities, and retrofitting unimodal neighborhoods around the needs of people outside cars.

"Quite a few jurisdictions have VMT reduction targets," Litman adds. "But these are usually presented as climate action – like we’re going to force people drive less in order to achieve this noble goal of protecting our globe ... But if we reframe it around the fact that strategies that reduce milage also increase affordability, I think we'd have a lot more success.

"We’re not just shifting money from highways to sidewalks and transit," he continued. "We are responding to what people want by creating more affordable, inclusive, healthy transportation system."

Litman acknowledges that comprehensive transportation affordability isn't likely to become a major presidential campaign issue anytime soon — at least until the U.S. starts broadcasting the percentage of walkable neighborhoods on gas-station-sized billboards along the highway. Still, he argues that Americans do care about the high price they're paying for basic mobility, and not just because of our quadrennial freakout over fuel costs.

And if that's true, Litman says it high time that we start analyzing transportation affordability impacts whenever we're considering new transportation projects and policies, including their indirect costs for people who may not drive at all. Advocates, meanwhile, might shift their messaging to focus on how ending car dependency would radically decrease how much our households spend — and increase our liberty to enjoy our hard-earned money, our neighborhoods, and our time with those we love.

"Affordability means freedom," he adds. "We need to emphasize how [transportation costs] affect people’s lives — especially in times when we're financially stressed."