As the presidential election comes to a furious conclusion, both parties are playing the sprawl card.

Both the Trump and Harris campaigns are putting forward plans to alleviate the nation’s affordable housing crisis by developing new homes on thousands of acres of federal lands, even as more Americans want to live in places where schools, parks, health care facilities, and entertainment are in short distances from their homes.

Former President Trump has touted a Utopian (dystopian?) vision of designing 10 “freedom cities” in vacant plots complete with flying vehicles, baby bonuses for families, and tented settlements for homeless individuals for more than a year.

Vice President Harris has decried the cost of housing in the presidential debate and on the campaign trail and released an ad announcing plans to build three million new homes. She hasn’t specified what kind of development she wants or where it would occur, although her campaign has referenced federal lands and she ran ads in Nevada and Arizona touting $25,000 in financial assistance for homebuyers.

The topic — bubbling way under the surface of national debate — was reignited at the recent vice presidential debate, where JD Vance was asked whether the Trump campaign would seize federal lands to accomplish Trump’s goal. Vance suggested, yes, replying that the tracts “aren’t being used for anything” right now.

“They're not being used and they could be places where we build a lot of housing,” he said. “And I do think that we should be opening up building in this country.”

The need for affordable housing is acute. The country is facing a housing shortage of 4.5 million homes, according to a Zillow analysis, while some housing advocates say the number of rentals needed to ease the burden of housing costs on low- and middle-income Americans is as high as seven million.

But there are widespread disagreements about where those units should be located. Trump’s China-inspired ghost cities on the frontier will likely never happen, but confusion reigns because neither campaign has released specifics about which federal properties the candidates want to exploit nor how their plans could contribute to disorganized, unregulated development already choking America’s countryside.

“I don’t think the same guy who wants a small federal government also wants to build a city in a place where it hasn’t happened before,” said Laura Foote, executive director of YIMBY Action, a national network of pro-development advocates that makes endorsements in elections. “I know they have not engaged with anybody who might help them execute such an idea. The Harris Administration wouldn’t do this, and the Trump administration wouldn’t know how to do this.”

The Biden administration has taken multiple steps to repurpose vacant federal land for housing in both urban and suburban areas. Last year, the Bureau of Land Management conveyed a five-acre parcel to Clark County to build 195 apartments for low-income seniors in the Las Vegas metro area and this month, the agency sold 20 acres of public land in a fast-growing Las Vegas exurb that Clark County will convert into 210 single-family homes. The Bureau is currently working with local Nevada governments to develop about 15,000 new homes on 562 acres of public land in the Las Vegas Valley.

At the same time, the federal Department of Transportation is looking to streamline requirements for getting federal loans to build housing and convert commercial properties near transit hubs. And the USPS is moving to repurpose thousands of surplus facilities located in dense urban areas that could be used for affordable housing while other agencies are releasing rules to make it easier to revamp unused federal buildings for housing for people experiencing homelessness.

Still, sprawl is happening unabated, particularly in the Sun Belt. Some of the country’s fastest-growing counties are in regions, such as near Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston, where there are few zoning regulations and land is relatively inexpensive. But these areas lack frequent public transit and are susceptible to climate hazards such as drought, fire, and flooding. In parts of Arizona and Nevada, where there is a lot of federal land, temperatures are soaring while droughts have led to water shortages in both states spurring drastic conservation efforts.

“Unfortunately we’re seeing damaging and scary climate events with increased climate intensity and communities historically marginalized by land use and transportation policy which face more exposure to climate events,” said Katharine Burgess, vice president of Land Use and Development at Smart Growth America. “Future development should not compound risk further, especially for communities facing economic vulnerabilities.”

So what's the big idea?

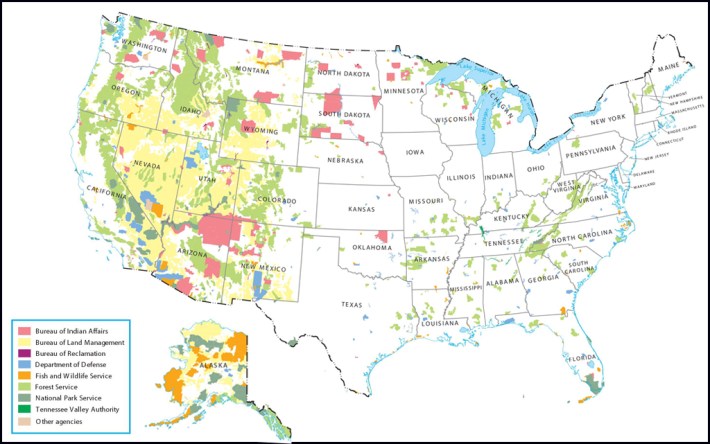

Both presidential campaigns could be looking at vastly different types of properties. The federal government owns about 640 million acres of land, about a quarter of all land in the United States. A significant amount of that, 155 million acres, is used for livestock grazing and lacks livable infrastructure of any kind, let alone water and sewer lines. But the federal government owns a variety of underdeveloped parcels such as parking lots adjacent to federal buildings in dense urban areas, especially around Washington, D.C. and northern Virginia, as well as tracts on military-owned lands. (The federal government owns 2.4 million acres, or 9 percent of land, in Virginia, mostly in the mountain west, and 25 percent of the land in Washington D.C.)

Housing and transportation advocates are trying to push both campaigns to prioritize housing in areas with access to transportation, jobs, and infrastructure such as schools, parks, and hospitals, that can lead to a high quality of life.

“We have major mismatches where jobs are and where there’s affordable housing available and we have to fix that,” said Flora Arabo, national senior director of State and Local Policy of Enterprise Community Partners. “Developers of both market-rate and affordable housing are interested in those areas, but it’s not cost-efficient or feasible to build in places that don’t have basic infrastructure like roads, water and sewers.”

The Harris campaign is seen as more likely to push to build multifamily units on federally owned infill sites in cities, advocates believe, although the campaign hasn’t cited these areas specifically.

Trump officials have been less clear about their plans. The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 promotes homeownership, single-family zoning, and fewer regulations towards development while Trump officials, including Vance, have blamed undocumented immigrants for causing the housing crisis — a charge that has been debunked.

Arabo believes there isn’t a binary choice between transit-oriented development or sprawl, but that the federal government should build in areas where they can achieve real density.

“Our job is to make sure that all people have the choice of living in the community that they choose and that they’re able to afford to live there,” she said.