If you build it, they won't drive.

Cities can dramatically reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by rezoning single-family housing areas for denser, mixed-use developments, according to a new study that reaches familiar conclusions that take on a new urgency in an era of twin climate and housing crises.

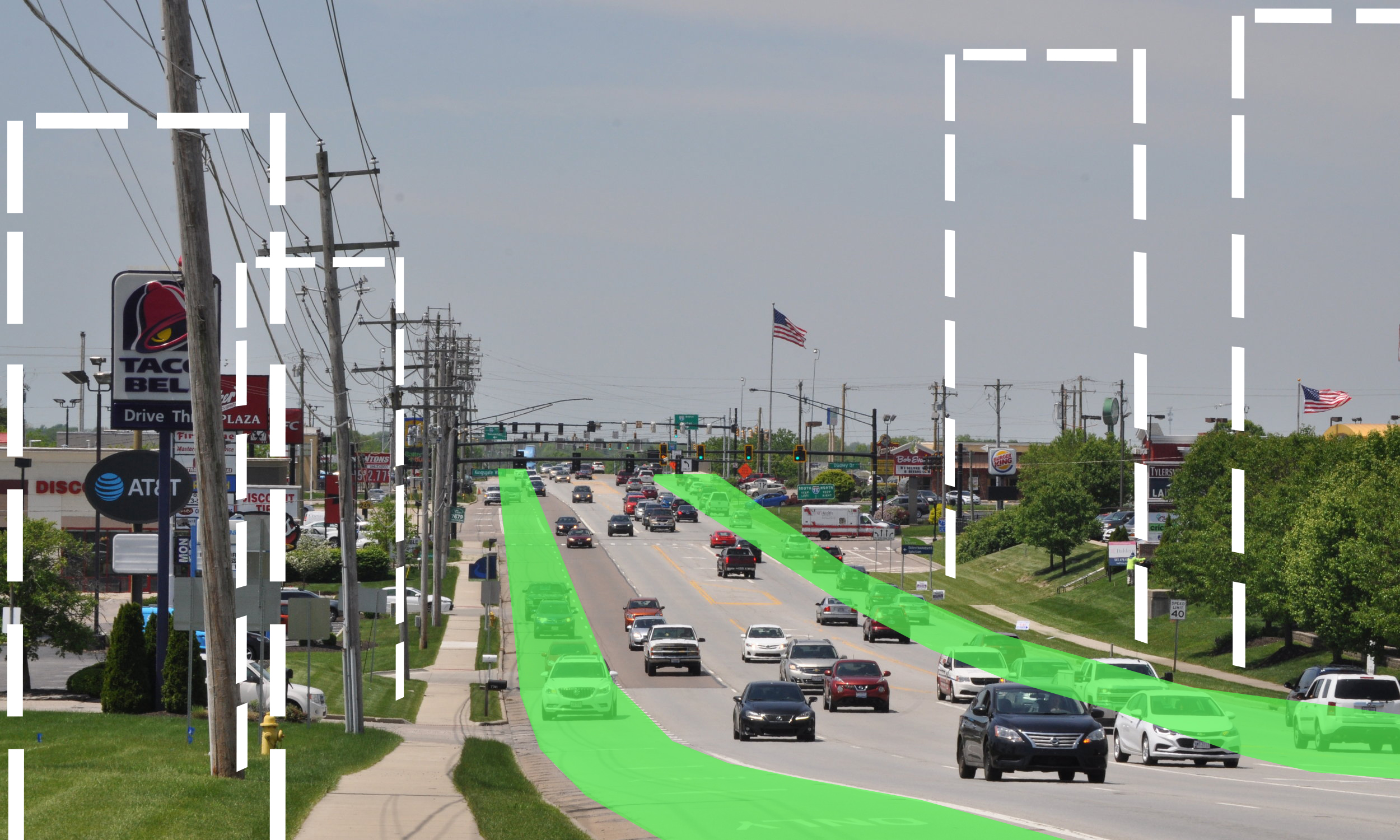

The Rocky Mountain Institute researchers used mobility data from Replica to first estimate the vehicle miles traveled in different neighborhoods, and then model the impacts of building new housing in existing neighborhoods where residents drive less.

In most states represented in the survey data, the researchers defined an ideal neighborhood with at least one-third of housing in denser forms like townhomes, apartments or duplexes. Here, residents’ share of vehicle miles traveled were in the lowest 10th percentile. If 90 percent of new housing built in the next decade matches the density of the ideal neighborhood, 31 million fewer tons of greenhouse gas emissions from driving would be released annually in 2033 – equivalent to removing more than 6.5 million cars from the road.

“[The conclusion] is supported by a body of research going back to the 1970s,” says Jonathan Levine, a professor of urban planning at the University of Michigan. “Our cities and close-in suburbs tend to be lower carbon zones — not low enough, but lower compared to more remote suburbs and exurbs.”

Single-family zoning ordinances tend to be exclusionary: nothing else can be built in these neighborhoods. That means a trip to the grocery store, the post office, pharmacy or a litany of other mundane errands tend to require a car. Single-family zoning covers 75 percent of residential land in the United States. It’s a big reason that American cities are sprawling, car-dependent, and racially and economically segregated.

Pedestrian pathways breaking up the cul-de-sac road layout are a simple improvement that can make such a big difference to an otherwise suburban environment.

— Oh The Urbanity! (@OhUrbanity) March 17, 2024

(Saskatoon, Saskatchewan) pic.twitter.com/26Lj5aODXo

By contrast, many European cities have a more porous understanding of what such residential neighborhoods should look like, Levine said.

“In Germany, there is such a thing as single-family zones, but there are [other] allowed uses,” he said. “It might include a grocery store — because in the German philosophy, of course, you need a grocery store nearby to buy food.” That proximity allows people to walk or bike for some of their most basic daily trips, even if they may still be commuting longer distances to work, school or other stops along the way.

The Rocky Mountain Institute also found that land-use reform would do best in states like Texas, Virginia and Washington because these states are experiencing rapid population growth. If the growing population continues to live in ever-sprawling suburbs, it will be impossible to reduce their vehicle miles traveled.

Creating support for land-use reform is easier said than done. In Dallas, for example, Adam Lamont founded Dallas Neighbors for Housing in 2019 after his neighbors in a single-family zone rejected the construction of townhome and apartment developments nearby.

Since then, the City of Dallas has released a proposed comprehensive land use plan called Forward Dallas, which espouses pro-housing policies that could allow for the “missing middle” of housing to get built. Residents like Lamont see the plan as an opportunity to make their neighborhoods better, but it’s also prompted a lot of hand-wringing from others who don’t want the character of their neighborhoods to change. (A similar not-in-my-backyard complaint is being made against Mayor Eric Adams’s “City of Yes” housing initiative, which would eliminate parking minimums and allow developers to build, as he put it, “a little more housing in every neighborhood.”)

“It’s not like, ‘Oh we should allow anything in a neighborhood,’ but we have to get past this idea that this area is only for residential and this area is only for commercial,” Lamont said. “Really, the goal in Dallas should be to reduce the number of cars by one per household — you can get around with just one.”

Lamont said that neighborhoods like Old East Dallas, with its modestly sized Craftsman-style homes built before car culture put a chokehold on urban planning, could and should look like that; people tend to want to move to those neighborhoods, with their beloved local coffee shops right across the street from a park to which neighbors can walk or bike easily, even in the Texas heat.

In the U.S., Levine said, planning policies tend to cater to residents who are suspicious of change or want to maintain the status quo. “There are people who look at these issues [at a policy level], people who already live in a neighborhood, and people who could live in a neighborhood,” he said. “The last two are equally important groups — but neighbors who are afraid of change have a relatively outsize voice in articulating their desire.”

But increasingly, younger constituents are advocating for mixed-use and higher density developments — not only for more sustainable communities, but more affordable ones, too. A few years ago, Minneapolis became the first U.S. city to scrap exclusionary zoning; it also got rid of parking requirements and lower lot size minimums. The result: while rents soared in other parts of the state, Minneapolis''s housing supply grew by 12 percent, but rents only rose by one percent, according to a report from Pew.

And in Ann Arbor, where Levine teaches, young voters elected a city council with a distinctly pro-housing view.

“What we’re seeing is that renters who would be home-buyers are starting to understand their own self-interests,” he said. “It’s in policy reform towards housing abundance, in highly accessible areas. And they’re mobilizing for it with some great success.”