What if cities were required not just to build safe places for people to walk and bike, but comfortably cool ones — even if it meant spending as much on pedestrian and cycling infrastructure as we do on infrastructure for drivers?

That's the question at the heart of a recent paper from Victoria Transport Policy Institute, which posits a world where municipal leaders work tirelessly to improve their scores on a "Cool Walkability Index" that measures how comfortable people are outside cars even on the most sweltering days.

The idea was born more than 15 years ago when the researcher behind the paper, Todd Litman, consulted on walkability issues in the white-hot desert city of Dubai. As the planet continues to warm, though, it could prove to be an essential tool all over the world, he said in an interview.

"Put simply, increasingly extreme heat is killing people," Litman said. "In modern, economically-advanced, developed countries, the common solution is that you get an air-conditioned house with an air-conditioned garage, and when you want to go anywhere, you get in your air-conditioned car and drive to another air conditioned building. But that has very severe climate, health and financial [downsides]."

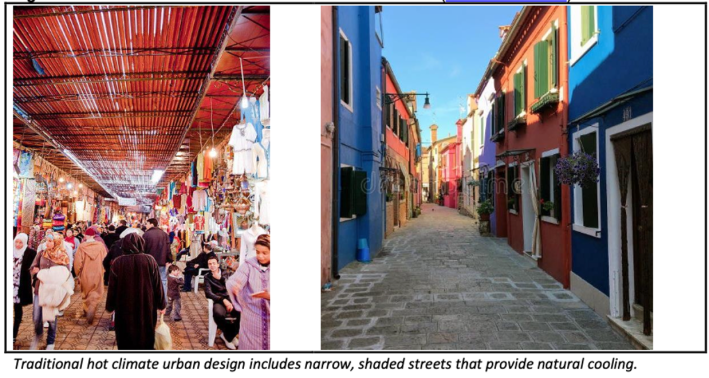

Some of the most effective ways to cool our cities — like using trees, awnings, and narrow, human-centered streets that keep walking spaces safely in the shade for at least 80 percent of the day — long predate the automobile, Litman said.

The same principles can be used to shade bikeways and off-road paths, too, like the solar panel-covered cycling paths that in countries like Korea and India.

In ultra-hot climates, though, Litman said, "shadeways" simply can't cool down cities enough. In those places, transportation leaders may need to invest in fully-enclosed, air-conditioned "pedways" if they expect anyone to walk at all.

"We would be fooling ourselves if we pretended that non-mechanical cooling is sufficient in those places that have extreme heat," Litman told Streetsblog.

"Even if we planted as many trees as we could and used reflective materials on every roof, there are some situations where that's still not enough. If we fail to build pedways in those places, we are basically encouraging people to shift from walking to driving — and that, to me, is the worst solution."

Even so, Litman is well aware that putting pedestrians in climate-controlled tubes is controversial — and could send the dangerous message that streets are only for cars.

A recent report from the Minneapolis Foundation, for instance, blamed the city's famous "skyways" system for "diluting the pedestrian traffic needed for ground-level retail" by diverting office workers onto enclosed bridges between buildings — not to mention doing nothing for unhoused people, who aren't always welcome in the privately-owned spaces which skyways typically connect.

A 2022 LAist article, meanwhile, called the California city's network of mostly-defunct pedestrian tunnels "a symbol of how cars changed Los Angeles." Its construction, the authors argued, "marked the beginning of the end of autonomy for children," since parents feared their children would be attacked by strangers in subterranean walkways even if they were protected from drivers aboveground.

Litman argues, though, that those past experiences should provide fuel for planners to figure out how to do pedways right, not to dismiss them entirely — especially when extreme temperatures don't give them much of a choice.

Efforts by transit agencies to curb antisocial behavior in their vehicles and stations might serve as a model for keeping pedways safe, he said. He also says tunnels and bridges can become vibrant third places — if they're designed with care, and integrated with shopping, recreation, and other services, rather than walling walkers off from the rest of the world.

"What does it mean to build a truly inclusive pedway system?" Litman asked. "If you’re an urban planner in, say, northern India, how can you design a climate-controlled air conditioned walkway that allows diverse populations to enjoy that cooling? I do think it’s possible."

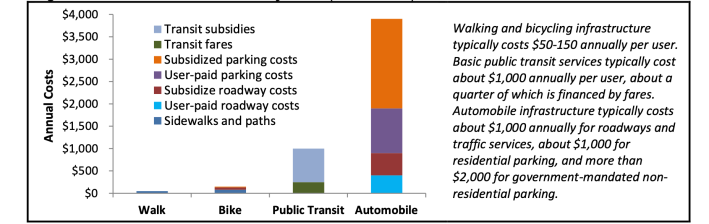

Litman acknowledged that building super-cool cities won't be cheap, and that a standard pedway can run about $10 million per mile. Still, he argues that amount is "comparable to the cost of adding an urban arterial lane in U.S. cities" — and we almost never blink at spending that, despite the fact that adding lanes doesn't even reduce congestion.

More to the point, he argues that pedestrians deserve that scale of investment, at least when you take into account the importance of walking in our lives. A previous study Litman conducted found that 12 to 25 percent of trips are taken on foot, but most jurisdictions spend two percent or less on sidewalks, or around $50 per resident per year. If we simply gave pedestrians their fair share, though, he says even the most expensive pedway system might be well within reach.

"Departments of transportation and local transportation agencies have no problem spending hundreds of millions of dollars on urban highways so a few thousand motorists can drive from one place to another," he added. "We should be willing to spend comparable amounts of money to accommodate pedestrians, if that’s what needed."

Of course, many U.S. cities fail to keep track of where their sidewalks and curb ramps even are and keep them in halfway decent shape, never mind replacing them with a whole ecosystem of fully accessible, air-conditioned walkways — something Litman also recognizes. Still, with deadly heat waves on the rise, it's time to think big, no matter how low the bar is right now — or at the very least, to hurry up and plant some trees, he said.

"I'm an advocate for active transportation," he said. "And [the Cool Streets approach] is really about answering the question; what would it take for people to look people to look forward to walking — even in a hot climate city?"