A long, sweaty wait at an unsheltered bus stop for a ride that only comes once an hour. A sweltering walk to a grocery store that's two miles away because the city zoning code doesn't allow developers to build a closer store in your neighborhood. A brutal bike ride to work on an unshaded street that your local traffic designers have stripped of all street trees in the name of keeping drivers safe if they happened to run off the road.

For Americans outside of cars, these aren't just hypotheticals, but a daily reality. And they're also a serious health threat.

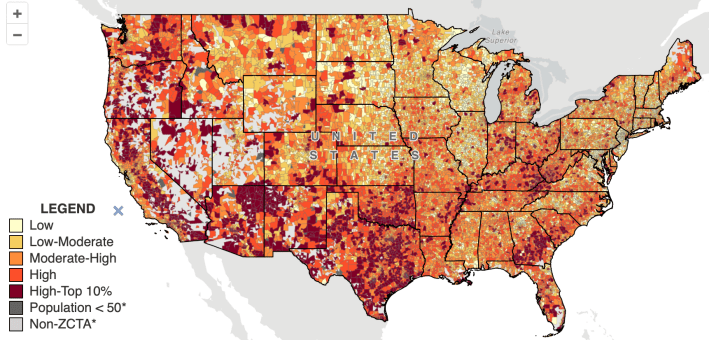

According to the CDC's new "Heat and Health" Index, residents of ZIP codes in which a high percentage of households don't own cars are at greater risk of heat-related illnesses, which claim the lives of about 1,220 people every year. Why? Because "those without a vehicle and without access to public transportation may be more likely to be exposed to extreme heat in the course of daily activities," the agency said simply.

And make no mistake: most of that "exposure" is the result of deliberate policy choices.

First and foremost, we can never forget that the extreme temperatures currently boiling U.S. communities are the direct consequence of climate change, to which the transportation sector — and overwhelmingly, cars and trucks — is the single leading contributor. And needless to say, that crisis is the direct result of decades of policy choices that have made solo travel in private vehicles our national default, while making walking, biking, and public transit punishing or impossible vast majority of trips.

We tend to talk less, though, about how the same structural forces that have made the car king are also making heat waves increasingly dangerous for everyone — especially for those who don't or can't drive.

The most obvious problem, of course, is infrastructure. Coating our communities in asphalt to build parking lots and ever-wider roads clogged with idling cars pushes up the average temperature in city neighborhoods by 15 to 20 degrees, creating an "urban heat island effect" that's almost impossible to mitigate without re-dedicating some of that blacktop and concrete to green space.

Just a few of the gazillion drivers sitting in their steel cages for 2 hours on the UWS, AC full blast, so they can dump their private property in public space, giving a shit about the climate catastrophe and public health. pic.twitter.com/dTepiY4SLz

— Radlerkönigin (@radlerkoenigin) July 16, 2024

The money we spend to build those heat-absorbing surfaces, meanwhile, is siphoned away from transit — which is especially bad news for riders during heat waves. Lack of federal funding for operations has left passengers across America waiting for buses and trains that come on painfully slow and unreliable schedules, often forcing transit riders to sit in stifling heat at outdoor stops which lack even the most basic shade shelters roughly four-fifths of the time.

Even stops that do have coverings are often designed with rain rather than heat in mind, as investigative journalists in Houston once found when they recorded temperatures inside plastic-lined shelters that were actually higher than riders experienced in direct sunlight. Some riders compared the shelters to "hot boxes" or "easy bake ovens."

And those simple design and funding failures can be fatal. For instance, investigative journalists in Maricopa County, Arizona found last year that a staggering 40 people died from the heat at bus stops between 2020 and 2022 alone.

Before they even arrive at those stops, of course, transit riders are often forced to endure a lengthy walk or bike ride just to get there, thanks in part to car-friendly land uses that push virtually every destination we rely on further away from where we are. Since extreme heat makes drivers drowsy, sluggish, and irritable, there's even evidence that fatal car crashes go up in some regions, potentially making those long slogs dangerous to boot.

And if those active commuters have the misfortune to trip or collapse from the heat along the way, they'll often land on unshaded sidewalks that could double as hot plates and easily give them third-degree burns and send them into multi-system organ failure.

Of course, the victims of heat-related illness in the street realm aren't all commuters. Many are unhoused people, like this anonymous San Jose man, who are too often denied legal access to air-conditioned indoor spaces of any kind, never mind the climate-controlled comfort of a personal automobile. Some are passengers in cars, like the 37 children who are left in hot vehicles every year (a number that some advocates say is a likely undercount, and could be drastically reduced if we mandated simple technology to alert the more than half of caregivers who leave their kids in the backseat unknowingly).

And the burdens of virtually all heat-related deaths and health conditions fall disproportionately on communities of color, who are both more likely to rely on transit and to live in neighborhoods exposed to extreme urban heat than their white counterparts.

Even if we did everything we could to stop the acceleration of climate change today, Americans no longer have a choice about whether they will be forced to endure dangerous heat waves every year. What we can do as we cut down emissions, though, is adapt to our stifling new reality and make heat waves less deadly, especially for people outside cars.

We can robustly fund transit operations so no rider has to wait for hours in the unforgiving heat.

We can put heat-reflective shelters, vegetation, and maybe even air-conditioned places to wait at every bus and train stop in America.

We can line our streets with native shade trees and green space, and treat our communities as complex, self-cooling microclimates rather than just places to drive through.

We can overhaul our land use policies so the closest grocery store or doctor's office isn't so far away that any would have to be crazy to bike there when the mercury rises.

We can house the unhoused who are dying of heat on our sidewalks and benches, or at the very least create cooling stations to help them survive.

We can mandate rear-seat detection systems so no parent or caregiver ever forgets that their child is in the back seat on a hot day again.

And we can do all these things with an eye to the profound intersections between the impacts of car dependency and structural racism. Because if we don't start using every policy tool we can to beat the heat and its many inequitable impacts, we'll never confront the more fundamental reasons why the Earth is warming so rapidly in the first place.