A series of road safety projects in Seattle had no negative effect on local businesses' bottom lines and in many cases boosted them, according to a new study — undermining the persistent myth that saving lives will undermine economic growth.

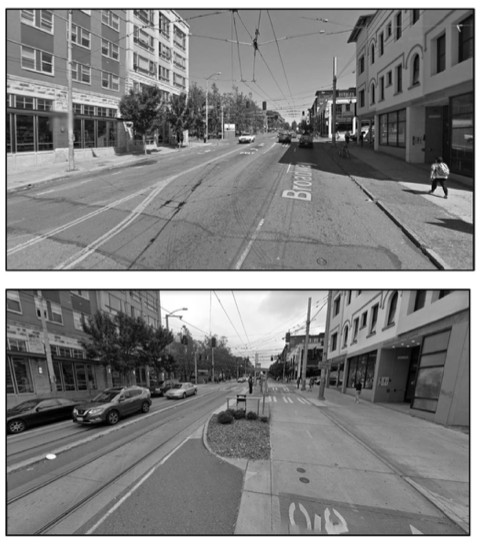

Researchers at the University of Washington found that seven roadway sites that were targeted for safe streets interventions such as road diets, bike lanes and "woonerf"-style street redesigns generated about 5 percent more taxable sales than comparable comparison sites nearby, at least in the seven years after the changes were made.

The researchers acknowledge that it's not a statistically significant difference, but even with the small sample size, the study is of the largest on the economic impacts of Vision Zero projects, providing solid evidence that calmer streets certainly didn't hurt Seattle's local economy — even if they had to remove a few parking spaces to get them built.

“Business people worry — even if they don't really have any evidence — that ‘my favorite customers park in front of my store, and if they won't be able to do that, they won’t come,’" said Andrew Dannenberg, who co-authored the paper. “The bottom line is, the places that had these interventions had about the same sales revenues as the ones that didn't have any interventions — and in some cases, it may be that people being able to walk in your store may actually bring more people in than just those who can park there.”

Still, Dannenburg acknowledged that it's been hard for researchers to quash the assumption that things like bike lanes are unilaterally bad for business — even if skeptics have virtually no hard evidence to prove it.

Part of the problem is data scarcity. The master's student who conceived of and led the study, Daniel Osterhage, had to complete "a whole range of paperwork" just to access the sales data necessary to explore the issue, and even then, identifying comparable sites for comparison was a serious challenge, even in a big city like Seattle. (Streetsblog NYC had similar bureaucratic challenges when it compiled a similar study after a controversial bike lane project was completed.)

And the sheer paucity of Vision Zero projects in America makes the task even harder, since great comparison studies require at least several road interventions that went in around the same time and weren't ripped out in subsequent years.

Those sorts of limitations help explain why only a handful of papers on the economic impacts of safe streets have been published, and they've tended to focus on isolated projects in big urban centers like New York City, San Francisco and Toronto.

"It's a matter of interest, resources, and access to data," Dannenberg explained. "This is an unfunded study [that started with] a student doing a master's thesis, so he's got the time and he's got the motivation, because he wants to be able to get this degree. But for a paid researcher to do it, somebody has to want to put some money and time into looking at it. And it just hadn't been done on a larger scale before."

Dannenberg hopes that his study will at least cast doubt on the knee-jerk belief that safe streets projects are a death knell for local shops and cafes, and motivate communities to find out if the opposite is true. And once they do, they can shift the conversation towards how to make safe streets a default, rather than constantly balancing them against feared economic "harms" that might not even be real.

“When they wanted to cut down on smoking in bars, the bar owners said, ‘Oh, if people can't smoke here, they won't come drink!’" he added. "But after they banned smoking, the bars did just fine. It's about being able to defuse an economic argument. … We can make it safer for pedestrians and not do economic harm to the businesses.”