Native American communities have long reported America's highest rates of pedestrian deaths — and it will take fundamental shifts to how we build our infrastructure and engage Native communities to correct that horrifying disparity, experts argue.

In a recent webinar from the nonprofit America Walks, a panel of professionals working in three tribal areas explored how they're addressing pedestrian death their communities, as well as the the root reasons why American Indians and Alaska Natives are so much more likely to die while walking on U.S. roads.

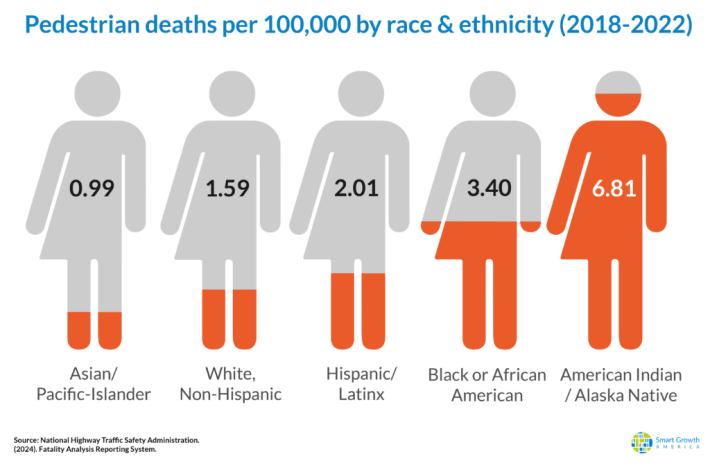

A recent analysis from Smart Growth America found that Native people are 4.2 times more likely to be killed by a driver while walking than their white counterparts — the highest per-capita death rate of any racial or ethnic group.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, much of the problem comes down to the sheer prevalence of high-speed roads with few sidewalks in Native communities, whether those routes run through rural reservations, car-dominated suburbs or even urban areas.

"Clearly, if we want to minimize fatalities, we need to keep speeds below 30 miles an hour — preferably below 20 miles an hour in areas where people are walking," explained moderator Ian Thomas, America Walks' state and local program director.

"Unfortunately, this is not the case in most tribal reservations in rural parts of the country, where vehicles travel at high speeds, and there are usually no sidewalks. Nor is it true in the urban and suburban areas of many cities where Native Americans reside and have to contend with excessively wide roads and no pedestrian projects."

Throughout American history, many Native Americans have been "forcibly relocated [to communities with] high-speed highways close to homes, schools, businesses, and other destinations," according to America Walks — whether to rural reservations that would later be torn apart by highways, or to similarly deadly urban areas, as in the Indian Relocation Act of 1956.

Many of those deadly roads were built without much regard for the safety of surrounding residents, or for those residents' unique cultural practices that might make them more vulnerable to car crashes. The Hemish people of the southwest, for instance, have a long tradition of running for "religious purposes, communication, health, travel, sport, war, hunting and to foster bonds between villages," and they continue many of those traditions today.

"“For thousands of years, the Pueblo has always been very much [engaging] in running and traditional cultural activities that involve walking and active transportation not related to vehicles," explained Sheri Bozic, who works in planning for the Pueblo of Jemez, N.M. where about 3,400 Hemish people currently live. "And so all the changes of the modern world have had a huge impact.”

One of those impacts was the construction of New Mexico State Road 4, which was built directly down the middle of the largest continuous stretch of land within the Pueblo. Bozic and her colleagues were able to successfully build a multi-use trail called the Hemish Path to Wellness along much of its length earlier this year — but they haven't yet been successful in finding funding for a bypass that would route deadly-fast traffic past the tribal lands, rather than straight through them.

That lack of funding or jurisdiction to build or redesign safe infrastructure was a common theme for all three panelists, who turned to quick-build solutions when money was tight.

In the Cherokee Nation of northeast Oklahoma, for instance, public health officials like Hillary Mead have focused heavily on adding things like crosswalks, speed tables, curb extensions and improved lane striping to keep pedestrians safe, especially in rural areas with lots of large, dangerous vehicles like cattle cars and hay trucks, as well as roads near schools. Young people have proven to be particularly outspoken about their walking needs.

“Definitely once we involved our youth, they were very good," Mead added. "They will tell you exactly what's going on in their community and how safe they feel walking down the street.”

Insights like that are particularly critical in the context of under-resourced tribal governments which struggle to collect reliable data on road conditions overall, never mind qualitative data on the nuances of the pedestrian experience.

That's part of why public health researchers at the University of Montana used an innovative app called "Our Voice" to help residents of the Flathead Reservation share their observations of what it's like walk in their communities, by taking geo-tagged photographs and writing testimonials even when strolling in remote areas far from a wi-fi router.

"Our goal is actually to improve 'physical activity security' among older adults, [and that means] physical and economic access to sufficient safe and enjoyable physical activity to meet not only their health needs, but to promote physical and emotional well being and social connectedness for an active and healthy life," explained Maja Pedersen, one of the researchers.

"What we found through some of our early work doing community-based participatory research is that safety is a major issue for older adults in participating in physical activity."

While most Native American communities have significantly shorter average lifespans and fewer elders than the population at large, the Flathead Reservation actually has a higher proportion of senior citizens than the rest of the U.S., and those populations are significantly less likely to drive.

While the panelists didn't emphasize it, other researchers have said that demographic differences in Native communities, like higher rates of poverty that puts vehicle ownership out of reach, higher rates of addiction that leads to impaired driving and walking, and less access to healthcare may all play role.

Regardless of who they are and where they live, though, all three panelists emphasized that building better infrastructure and conducting better community engagement can save Native Americans' lives — and the time to do it now.

“[It's not just rural areas;] we also have fatalities in the urban areas in cities, where Native Americans also live," added Bozic. "We just need to do better with the road designs; we need to mandate and incorporate pedestrian facilities be constructed for every roadway that's constructed.”