The majority of American drivers would happily accept technology that warns them to slow down when they're exceeding the speed limit — and a surprising number are open to systems that prevent them from hitting deadly velocities at all, a new survey finds.

More than 60 percent of drivers surveyed by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety say they would accept a "passive" version of Intelligent Speed Assist technology that automatically reads the local limit and then provides an unobtrusive visual or auditory alert to remind drivers to slow down. Those systems will come mandatory on all cars sold in the European Union starting next month, and are already available on some U.S. vehicles; the NTSB called for a similar requirement here last year.

And despite loud opponents who insist that "speed limiters" are a restriction on freedom, about half of the survey respondents said they "wouldn't mind" a more aggressive type of speed governor that makes it physically harder to press the accelerator, or even one that automatically throttles the speed of the vehicle to match the local max.

"These findings are exciting because they suggest American drivers are willing to change how they drive to make our roads safer," David Harkey, president of the Institute, said in a release. "The conventional wisdom has always been that speed-restricting technology would never fly in our car-centric culture."

Is a speed governor ordinance on your November ballot? Exactly 100 years ago such an initiative was on the ballot in Cincinnati, after 42,000 residents signed petitions demanding a law that would mechanically limit motor vehicles to a top speed of 25 mph. This is a "vote yes" ad. pic.twitter.com/gkSEG91xTV

— Peter Norton (@PeterNorton12) November 4, 2023

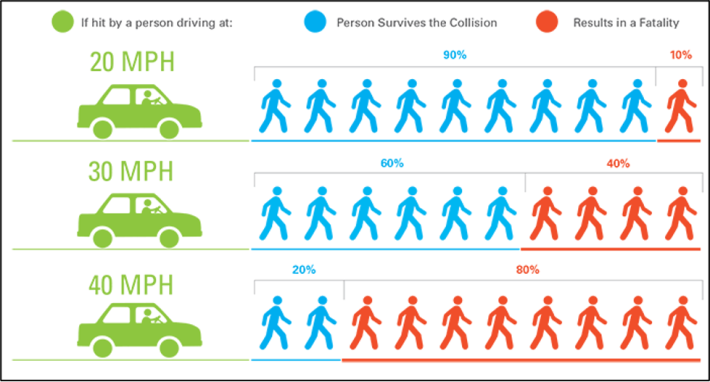

Even in the earliest days of the automobile, early versions of speed limiting technology — which, at the time, simply capped top engine speeds at a pre-set limit — were seen as a critical tool to rein in what was already recognized as the single biggest factor in rising road deaths. Studies show that pedestrians, in particular, are far more likely to die when struck by vehicles traveling 40 miles per hour, a velocity that's all too common on neighborhood arterials designed for 35 miles per hour or more.

As speed limiters have evolved, though, U.S. regulators have been slow to explore even the most ancient versions of that technology, routinely allowing cars that are capable of exceeding a 160 miles per hour or more to roll off the lot — and onto roads where the maximum speed limit anywhere in the country is only 85.

Now that more advanced forms of Intelligent Speed Assist are poised to become ubiquitous around the globe, advocates are scrambling to figure out how to get U.S. regulators to mandate them — and how to get consumers not to shut those systems off once they're actually installed in cars. Nearly 60 percent of the surveyed drivers said they'd be OK with an alert-only ISA system, and 51 percent said they'd accept an "active" system that made it harder to hit the gas pedal. A full 48 percent — a very sizable minority — would accept one that actually limited their speed.

Tellingly, those drivers said they'd be slightly more accepting of ISA if most other drivers had systems of their own, though that acceptance went down as the technology got more aggressive. And 70 percent of drivers in all groups "agreed they would want ISA in their next car if their insurance company lowered their premiums based on evidence that they don't speed," or if the threshold for intervention was raised to 10 miles per hour over the limit rather than just one or two.

The latter idea probably won't seem acceptable to safety streets advocates who recognize just how many U.S. cities already set speed limits dangerously high — and how many routinely design roads to encourage far faster velocities than the numbers printed on roadside signs. Still, as we work towards accomplishing the generational challenge of lowering speed limits and designing roads to match, the Institute is optimistic that speed limiters in vehicles could save a lot of lives — and that since U.S. drivers are less averse to them than we assume, "a federal mandate could help overcome resistance."

"This technology enables nuanced interventions that were Neve possible in the past," added "Harkey. "The next step is to encourage automakers and driver sot embrace it so we can begin saving lives."