Hundreds of U.S. cities and nearly 1,300 communities worldwide have “achieved” Vision Zero, a new report claims — but a lot of them got to zero fatalities because their streets are so dangerous and car-centric that few people dare walk or bike on them.

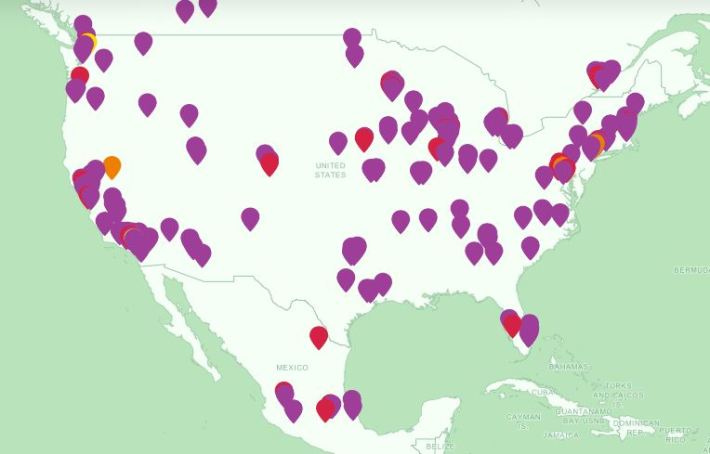

In the 10th edition of its annual road safety report, the German safety inspection company DEKRA found that 1,274 cities across 26 countries had recorded at least one year with zero traffic deaths since the analysis was first conducted. A whopping 235 of those communities were in North America alone.

That list — which excluded places with fewer than 50,000 residents and scores of South American, Asian and African countries for which data was not available — did include some the most ubiquitous poster children for the movement to end traffic deaths and serious injuries, including safety-focused cities in Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands, and more.

It also includes Hoboken, N.J., which made international headlines for an aggressive intersection “daylighting” program that helped eliminate crash deaths in the Mile Square City for seven years in a row.

Many of the other U.S. communities on the list, though, don’t have Vision Zero programs at all — and some are so explicitly designed around automobiles that few people even attempt to walk or bike.

Take Fort Myers, Florida. Apparently, at some point in the last 10 years, the Sunshine State town reported 12 consecutive months with no road deaths to the International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group, from which DEKRA sourced the stats for its map. But earlier this year, this road in the City of Palms was the site of two pedestrian deaths in 48 hours. Smart Growth America recently ranked the larger Fort Myers-Cape Coral metro area as one of the 20 most-dangerous places for walkers in the whole country.

Or consider Surprise, Arizona. This city of 154,000 also appears on the DEKRA map, though its glorious year of Vision Zero certainly didn’t happen in 2018, when an unidentified male pedestrian was killed here. Note the abrupt end to the sidewalk.

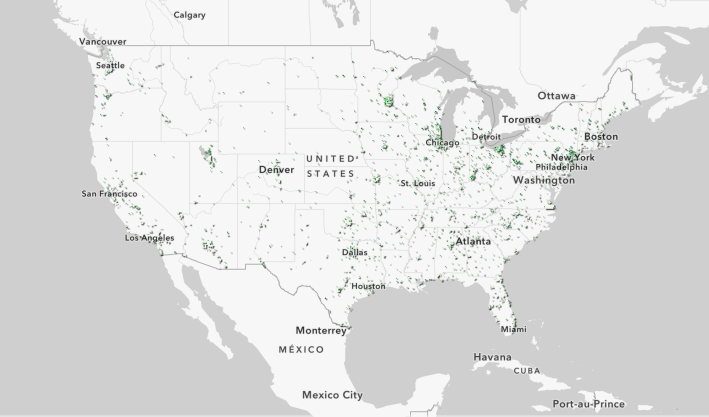

If DEKRA’s data seems a little sketchy, remember that US DOT produced its own U.S.-specific version of this map a few years ago, documenting hundreds of communities with more than 5,000 residents that had reported at least one year of Vision Zero success between 2017 and 2021.

It includes places like Brentwood, Missouri, a two-mile-square city that’s bordered by two interstates and replete with big box retail and six-lane arterials where it’s exceedingly rare to see anyone on foot.

Somehow, Brentwood avoided killing anyone for all five years that the DOT studied — but certainly not by making ambitious infrastructure improvements.

(Personal note: The intersection below is where a local St. Louis biking safety class in which I once participated takes its students to put their riding skills to the test on the most dangerous road they can find.)

Of course, the US DOT's map relies on imperfect data of its own. As Seth LaJeunesse recently pointed out in Smart Growth America, at least half of pedestrian and cyclist crashes go unreported to the police, including some fatal crashes when vulnerable road users didn't immediately die of their injuries.

But the uncomfortable truth is, thousands of car-dominated cities can and have “achieved” — or at least lucked into — a dubious version of Vision Zero success. And countless transportation leaders are patting themselves on the back right now for building safer places, even when they've done the opposite.

In some ways, that isn't much of a surprise. Bumper-to-bumper traffic jams are an effective way to prevent drivers from picking up enough speed to kill people, even if the slashed transit budgets that helped create that congestion have voided the streets of walkers. People who live in gated suburban cul-de-sacs do encounter fewer reckless motorists … provided they never leave their safe labyrinth of local roads and enter the deadly arterial that’s almost guaranteed to lie just past its borders.

And as Wes Marshall points out in his excellent new book, “Killed by a Traffic Engineer,” designing for auto-domination is a sure-fire way to send a message to other road users that this space is not for them — and most rational pedestrian and cyclists will hear message loud and clear. The ones who can't just climb inside the protective metal armor of a car, though, may eventually find themselves out on the road anyway — and eventually, their deaths may break their cities' fragile Vision Zero streak.

“As it stands, it’s easy for very dangerous streets and intersections [and communities] to be deemed safe: it’s because we’ve scared away all people who want to walk or bike,” wrote Marshall. “In the end, where we don’t find crashes could be just as dangerous, if not more, than where we do.”

DEKRA rep Wolfgang Sigloch acknowledged that the cities on his company's map aren’t all safety leaders worth imitating, and that while some “will have a set of concrete measures in place and might therefore be able to give some additional insight,” others “just have been lucky.”

As we strive for the true spirit of Vision Zero, though, maps like these serve as a critical reminder that eliminating road deaths by any means necessary isn’t enough.

City planners don't need to put everyone safety behind a windshield and an airbag; they need to build roads that force motorists to drive so slowly and carefully that people outside cars are unlikely to die even when a crash occurs. Safety is not merely about attacking the nodes in a local "high injury" network, as important as that work is, but about scrutinizing the places where no one is getting hurt because no one dares to travel there outside a private vehicle.

To build truly livable places, communities need to measure not only the absence of carnage and roadway "conflicts," but also the presence of people moving and interacting in public space — even if that movement has nothing to do with getting from point A to B.

Otherwise, we won't just fail to zero out road deaths. We'll zero out the vitality that makes our communities places worth living in.