People with disabilities have forced the San Francisco Bay Area to make key transit stations more accessible — a win that, hopefully, will provide a model for other agencies to act before lawyers get involved.

A coalition of people with mobility challenges and their advocates recently settled a lawsuit with the Bay Area Rapid Transit District, which "systemically failed to ensure full and equal access to its stations and services, in violation of ... the Americans with Disabilities Act,” a release from the group’s legal counsel said.

Those failures, the plaintiffs say, included a whopping 87 damaged or out-of-service elevators as well as several non-functioning escalators, making it virtually impossible to access stations for many people who use assistive devices or struggle to climb stairs.

“Many BART stations do have elevators and escalators, but they're frequently not working or in poor repair [from] very heavy use,” said Melissa Riess, senior staff at Disability Rights Advocates, which served as co-class council on the suit with Legal Aid at Work. “And when those elevators and escalators are out of service, that is a barrier to people with mobility disabilities; it means they have to either go hours out of their way to get where they need to go, or they just can't use BART at all.”

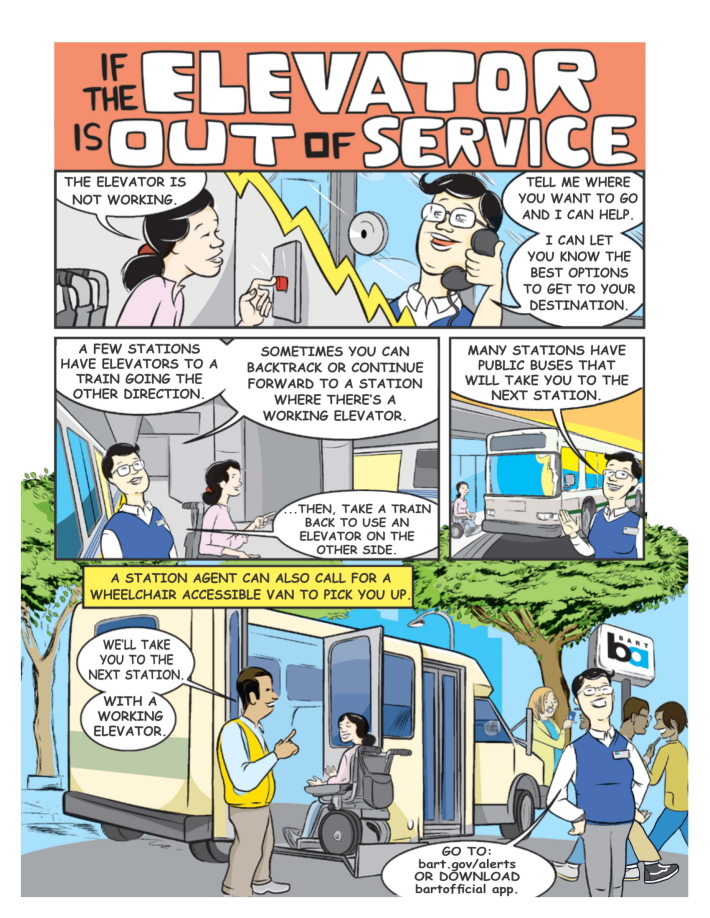

In the settlement, BART has agreed not just to fix that broken infrastructure, but to better communicate about outages to riders before they embark for a stop they won’t be able to use. Officials also agreed to new processes that will require workers to promptly address unsanitary conditions that can make accessibility infrastructure deeply unpleasant or outright unusable, to make a “reasonable best effort” to continue funding the agencies’ much-applauded elevator attendant program, and to implement a new complaint procedure for riders to more easily report outages and messes, rather than waiting for transit workers to find those problems on their own.

Those terms, Riess hopes, can help provide a blueprint for the 25 percent of US transit stations that don’t comply with the ADA, according to the most recently available federal statistics – including those like BART, which became the first agency to offer elevators in every station after earlier lawsuits, but hasn't always managed to keep them in working order since.

And since Americans with travel-limiting disabilities only drive for around half of their trips — non-disabled Americans, by contrast, drive for 67 to 78 percent, depending on their employment status — those station access issues can make the difference between full participation in society and a far more limited life.

“This is not just an issue in the Bay Area. … We're seeing all these transit agencies with aging infrastructures, and they don’t want to spend the money on pieces of infrastructure that are just so vital for people with disabilities — and for everyone, to make the system run more smoothly,” added Riess. “It's not necessarily glamorous work, but it really needs to be done — and luckily, we're able to use the Americans with Disabilities Act to push them to do what they need to do to keep this infrastructure where it needs to be.”

Riess acknowledged that not “wanting” to fix elevators isn’t the only reason so many U.S. agencies are struggling to keep their systems accessible. As Sen. Tammy Duckworth explained in a 2021 interview with Streetsblog, massive funding shortfalls accelerated by the pandemic have increasingly pushed accessibility improvements down transit agencies’ budget sheets, even after her groundbreaking All Stations Accessibility Act won these projects a meaningful but meager $350 million a year. New York City once famously estimated the cost of installing elevator upgrades at just 70 of its 472 stations at a staggering $5.5 billion.

“Even though making these stations ADA compliant may have always been a priority, it’s never been the top priority,” Duckworth said. “It’s always in the top five, but usually, something beats it out, like a safety issue or a necessary system upgrade. So the time just never comes.”

As with a similar 2022 settlement that Riess’s firm helped win in NYC, BART will have more than a decade to address its massive backlog of ADA fails. Specifically, the agency has 15 years to fix the 40 elevators most urgently in need of renovation, and it's committed to fixing the rest — with the unfortunate but necessary caveat that doing so might not be possible if agencies don’t win more funding or fill up their fare boxes.

“In the course of the discussions that resulted in the settlement, we acknowledged that we are in a time where ridership is down; since the pandemic, things are challenging for these public agencies,” Riess added. “And so that is reflected in more flexible timelines to make these repairs and obtain the funding that they need to [do it]. … The structure of the settlement is really [designed] to focus the repairs on the places in the system that are most in need.”

Of course, Riess wishes the disabled people of the Bay Area wouldn’t have to wait 15 years to get even some of their basic infrastructure fixed — and that it hadn’t taken lengthy legal negotiation to win that victory. Until more fundamental changes are made to center the needs if of transit riders with disabilities, though, she suspects similar suits will continue across the country.

“One of the biggest things that we can do is just to not view accessibility as this fringe issue that only affects a certain segment of the population,” she added. “Incorporating those principles of universal design into everything we do really benefits everyone.”