Editor's note: This article originally appeared on The New Urban Order and is republished with permission.

If you’ve booked a ticket on Amtrak.com lately, you may have noticed that prices can swing wildly depending on what day, time, and how far in advance you’re trying to book. If you’re a deal-seeker like I am, you may even book tickets with their “flex” fare, which can be refunded with no fees, and then keep checking back to see if ticket prices have gone down. Doing this, I’ve gotten tickets as low as $19 and other times shaved $20 off my initial ticket price, buying and refunding as needed.

I love Amtrak’s dynamic pricing because those cheaper tickets make it possible for me to visit New York more often. And I’m heartened to think that dynamic pricing enables Amtrak to fill more trains and earn more revenue. Three years ago when Amtrak delivered its five-year plan, it saw the potential of AI to manage unsold inventory and optimize supply against demand — and it made it work, seamlessly.

Despite these benefits, dynamic pricing is not that common in cities outside planes, trains, and Ubers. But that may be changing soon.

Dynamic pricing has been in the news lately because in mid-February, Wendy’s announced a plan to institute dynamic pricing on their digital menus. The idea was quickly slammed by customers. The price of food is a very touchy subject right now given its role in inflation, and dynamic pricing on basic sustenance felt wrong to many — particularly since fast food tends to thrive in food deserts where people already have few options.

But when a New York Assembly member, Angelo Santabarbara, proposed legislation banning the practice, I found the backlash a bit extreme and premature. Speaking to City & State NY, Santabarbara said:

“The use of artificial intelligence technology to calculate when surge pricing is going to occur, it's really opened up consumers to potential exploitation and manipulation by this technology. And so these business practices, when it comes to the food industry, it's something that needs oversight. In this case, it's something that we shouldn't allow altogether.”

But couldn’t dynamic pricing just as equally be a way to enable budget-conscious people to maximize their spending? Couldn’t it help businesses, nonprofits, and local governments cope with new post-pandemic economic patterns?

Dynamic pricing done well, like the Amtrak option, could be helpful for cities. London Mayor Sadiq Khan is currently mulling whether to use dynamic pricing on London’s transit system. And as of March 1, Transport for London is piloting reduced fares on Fridays when ridership rates drop by about 10 percent. London already has peak and off-peak fares, but this is taking the pricing model one step further. The pricing won’t be updated based on real-time demand as true algorithmic dynamic pricing would allow, but it’s a step in that direction.

Meanwhile, as New York City moves ahead with its congestion pricing plan, it is considering surge pricing to dissuade people from driving in on especially busy days and times. Unlike a train or plane ticket, the increased cost of surge pricing can be split across more people sharing the car, encouraging pro-environment and prosocial carpooling.

Dynamic pricing examples like these have a higher goal in mind: behavior change for a better city. For London, the goal isn’t really for the Tube to make more money — it’s actually to get people into downtown London, spending money there, helping businesses thrive, bringing in more tax revenue to the city. And for New York City, the goal is not just to reduce congestion, but to reduce pollution and improve quality of life for residents, while funneling money back into transit improvements.

Many industries are already using AI to create dynamic pricing, even if it isn’t overt. It’s underlying the rental rates of a lot of new, market-rate rental housing, for example. Why shouldn’t nonprofits and the public sector take advantage of dynamic pricing as well?

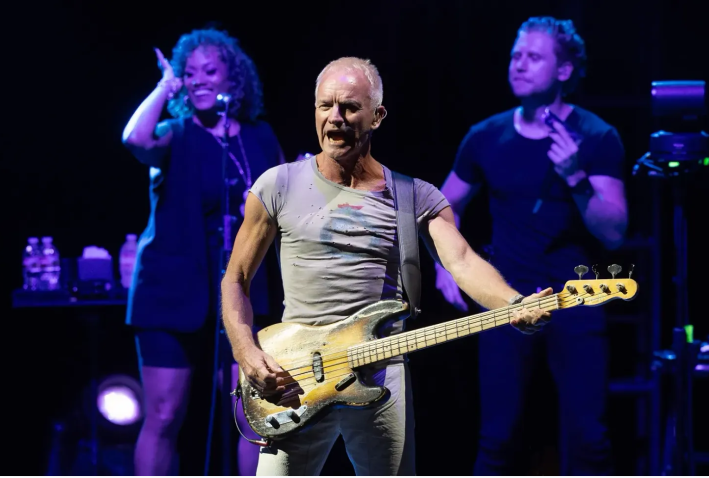

Museums and theaters are struggling in the post-pandemic economy, but could use dynamic pricing to fill seats and encourage ticket sales. Philadelphia’s Ensemble Arts now uses dynamic pricing to take advantage of high-demand events like two Sting concerts to reap the most revenue and sell out both shows. According to the Inquirer:

Out of the 4,800 available tickets in Verizon Hall (two shows at 2,400 seats each), about 100 tickets sold for $800 each; 2,000 tickets sold for $400; 850 sold for $300; 800 for just under $250; and about 1,000 tickets sold for $173. With service fees, the actual amount paid by patrons was higher.

Undoubtedly, they’re employing similar methods for less popular programs, reducing the cost of tickets to ensure seats are filled.

Government could consider how to use dynamic models to deliver subsidies and aid, which is too often bluntly doled out based on simplistic formulas. It’s time for these sectors to catch up, not try to legislate away dynamic pricing.

As cities cope with remote work and people’s changing schedules, they will have to think of ways to reap the rewards of high-demand times and yet also stoke demand on slow days. Dynamic pricing deserves a closer look, particularly as more widespread use of AI can make it easier for institutions, organizations, and even small businesses to make the most of each day.