Advocates have a powerful new tool in the fight to reduce driving: a new calculator that shows exactly how much their states would benefit if residents drove less.

Analysts at climate think-tank RMI have developed a new widget that shows, in just a few clicks, how communities might be transformed if they commit to a goal to reduce vehicle miles traveled by 20 percent per capita by 2050, as Minnesota did in 2023. Overachievers can even calibrate their goals to see how much a bigger reduction would impact their residents.

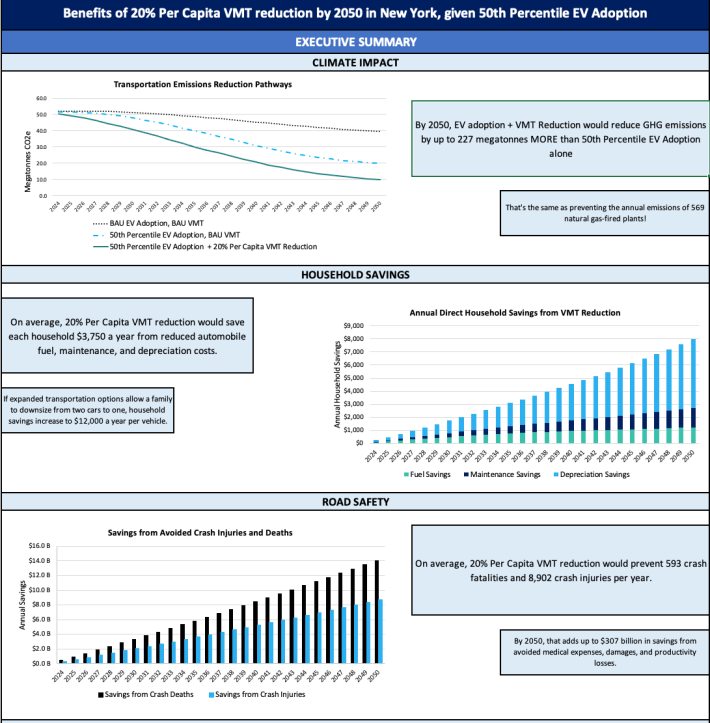

And that impact isn’t just about smog-free skies. In addition to tallying up the greenhouse gas emissions associated with less car travel— yes, even if motorists switch to electric vehicles — the calculator also quantifies how much state taxpayers would collectively save as car crashes plummet, public health outcomes improve, and traffic congestion eases along with VMT.

They even tote up how much the average individual household would keep in their wallets every year if they have fewer fuel, maintenance and vehicle depreciation costs —even if they don’t sell their cars outright, which the calculator assumes they won’t. And all those values are automatically adjusted for local factors, like each state’s projected population growth, likely future gas prices, and how much their local energy grid is projected to rely on clean sources over time, which determines how green any EVs on its roads will be.

“I really hope, in my heart of hearts, that people see that a different path is possible,” said Miguel Moravec, senior associate at RMI. “A more efficient transportation system not only leads to less pollution; it also leads to more cost savings, more equitable access, and even more economic development opportunities. We should all be asking ourselves: given our local context, what are the policies that can give people in our states real alternatives to how they get around?”

Moravec emphasized that hitting the calculator’s default 20-percent reduction goal is possible — and some states may be capable of going even further. Between 1996 and 2021, Washington state slashed household VMT by 16.67 percent, thanks to a series of policies that aimed to get commuters carpooling, encourage transit-orient development, and install more than 30 miles of light rail in urban areas. And that process began before the state formally adopted a VMT reduction target in 2008, or began exploring local car-cutting goals in 2021.

“Even though a lot of those [strategies] were focused on the urban core, Washington has plenty of rural areas, too,” added Moravec. “If they can do it, anyone can do it.”

Moravec acknowledged that a spreadsheet-based calculator can’t capture all of the benefits of reducing car dependence, and that RMI hopes to build on this version over time. A future version might explore, for instance, how much residents would benefit if sustainable transportation improvements allowed them to go car-free, or how much the public would save in avoided car-crash related serious injuries, which are often significantly more expensive than deaths; they’d also love to be able to plug in each state’s unique modal mix, and rapidly identify which strategies, specifically, can get communities to their VMT goals.

With states like Colorado, Maryland, and New York either committed to cutting car travel or considering measures to do so, Moravec hopes that this data will at least start painting the picture of why VMT reduction is important — and that advocates will color in the lines over time.

“[These estimates are] actually very conservative,” Moravec added. “And they’re not radical, either; [VMT reduction] has already been done in a lot of places, and it can be done in so many more.”