This time, progress went backwards. But now, maybe, it’s going back to the future.

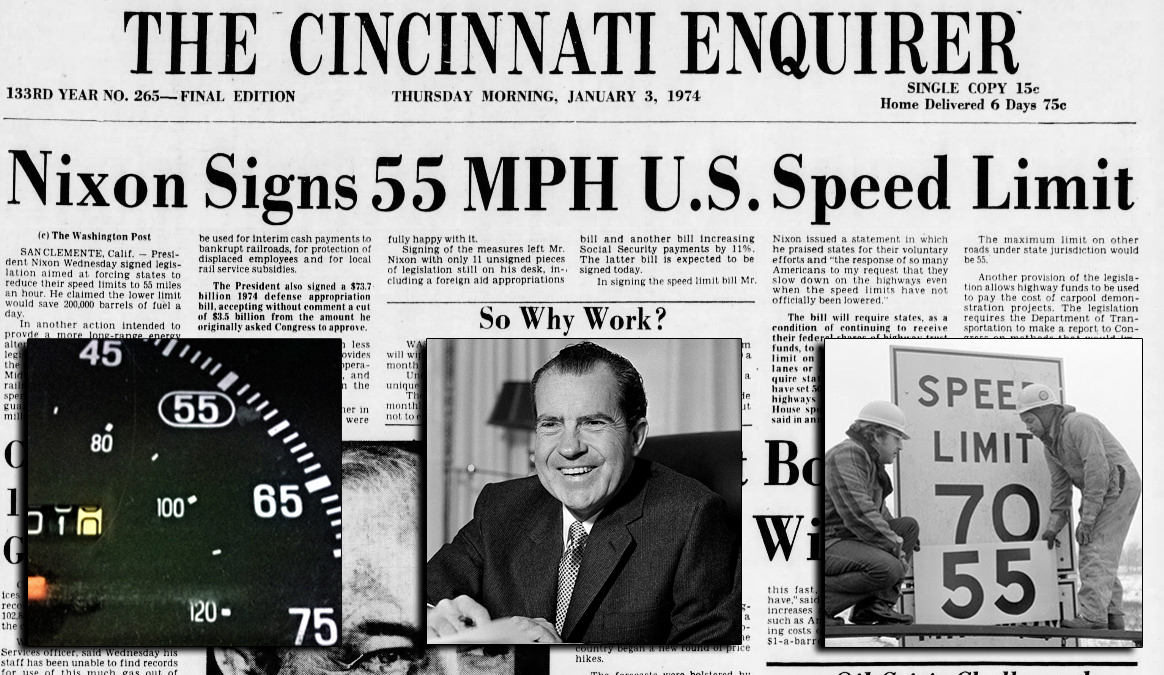

On Jan. 2, 1974, President Richard Nixon signed a National Maximum Speed Limit law that restricted highway driving at 55 miles per hour across the country in an effort to save fuel during the oil crisis. Yet for almost all of the next 50 years, states slowly undermined the law’s safety benefits and energy conservation.

Today, though, advocates are making progress to claw back those gains — aided, unfortunately, by reckless drivers who killed 7,500 pedestrians in 2022, a 40-year high.

“As more people connect the dots that higher speeds are a big contributor to our pedestrian safety crisis, we’ve been able to push states to do the work to lower speeds on streets that they do manage and allow more flexibility on that local and county level,” said Leah Shahum, founder of the Vision Zero Network. “Cities are pushing to set speeds based on actual safety needs and not a hand-me-down policy that’s existed for years.”

A promising start

It could have turned out better from the beginning.

Nixon’s Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act required states to cap speeds on divided freeways with four or more lanes in order for states to receive federal highway funds. Nixon resigned nine months later, but his successor, Gerald Ford, and Congress made the change permanent in January 1975. As a result, 29 states lowered their posted speed limits to just 55 miles per hour.

The measure was primarily conceived to conserve fuel during the country’s energy crisis. Middle Eastern countries launched an oil embargo the previous year that led to gas shortages and skyrocketing prices. But safety was not evoked in Nixon’s remarks about the bill.

Whether it was Nixon's intention or not, increased safety appears to have been a side effect of the lower speed cap. For a brief period in the mid-1970s, fewer people died on the roads. In the first year of the policy’s enactment alone, the number of fatalities fell by 16 percent, from 55,511 in 1973 to 46,402 in 1974, according to a National Research Council report conducted in 1984.

But some states sought to undermine the law by refusing to penalize speeding violations despite safety and energy conservation benefits. The law also counterintuitively forced several states, including New York, Maryland, and New Jersey to raise expressway speeds that had previously been set at 50 mph.

States officials eventually won out. By 1987, Congress permitted states to bump up speed limits to 65 miles per hour on rural interstate freeways despite protests from Mothers Against Drunk Driving and the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

And eight years after that, Congress lifted its regulations and allowed states to make their own rules. Several states set top freeway speeds at 70 to 75 mph. Texas, naturally, jumped to 85.

The changes may have had a catastrophic effect on the country’s health and safety, with a 3.2-percent increase in road fatalities between 1995 and 2005 that public health experts say accounted for 12,545 deaths that might not have occurred otherwise during that period.

Researchers also determined that fatalities rose nine percent on rural interstates and four percent on urban ones, according to a 2009 report in the American Journal of Public Health. And that study may have underestimated traffic deaths because the Fatality Analysis Reporting System database only reports deaths within 30 days of a crash, doesn’t collect data on crashes on private property, and relies on police reports, which are often incomplete.

“We’re seeing Autobahn-level speeds in the US, which means when you do get into a crash the risk of death is exponentially higher,” said Lee Friedman, a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health who co-authored the 2009 report. “Motor vehicle safety has improved [for car occupants] incredibly, but there’s a point where you reach a speed threshold where the probability of death is incredibly high. As our road systems allow us to go faster and car design has a better ability of stability and soundproofing, we habituate to higher speeds.”

So what should be done?

Transportation advocates have pursued different strategies to slow down drivers.

Groups like the National Association of City Transportation Officials have long sought to convince state departments of transportation to stop setting speeds by using the “85th percentile” strategy, or the speed at or below which 85 percent of motorists will drive on an open road. Instead they advise setting limits on major corridors like state-owned arterials and add slow zones in sensitive areas like schools. States like Wisconsin, Massachusetts, and Colorado are beginning to develop a more holistic strategy to review roadways, NACTO officials said — and in December, federal speed-limit-setting guidelines were updated to help more of them do so.

“Speed-setting practices across various levels of government share many of the same problematic flaws, especially a singular focus on motor vehicle speeds at the expense of safety of non-motor vehicle users,” said former NACTO spokesman Billy Richling. “We have seen some states move in the right direction.”

Adopting speed cameras along high-speed corridors and in sensitive areas has been another strategy. Chicago has added about 162 speed cameras near parks and schools. And New York City installed about 2,000 cameras, which write nearly six million tickets per year (even though a million or so incidents per year aren’t being recorded because drivers have used fake or obscured plates). In Australia, meanwhile, speed cameras are installed on highways at regular intervals, contributing to lower fatality rates on the country’s roadway system.

“They’re not the golden goose that solves the problems of all fatalities, but it’s the one difference between the US and other countries committed to Vision Zero, which is that they are committed to broad, systemwide speed cameras,” UIC’s Lee Friedman said. “If we have to concede we’re never going to get speed limits down then lobbying for speed cameras and the sell is that they pay for themselves.”

Other advocates are more optimistic that they can reduce speeds along deadly avenues. They have sought to get power from statehouses to add traffic-calming measures and lower posted limits along state roads in their communities. Shahum and her Vision Zero advocates worked with city officials to reduce San Francisco’s Cesar Chavez Street from six lanes to four and add a center median, rain gardens and bike paths to calm traffic. More recently, she convinced San Francisco officials to lower speeds from 25 to 20 mph in the Tenderloin, a low-income neighborhood with several wide-avenue arterials and one of the highest number of traffic deaths and injuries.

But some states and localities have gone backwards despite evidence that slower road speeds save lives. Several states are looking to boost speeds on their highways by another five miles per hour. And in New York City, the Adams administration has scuttled measures to redesign dangerous streets in the Bronx and Brooklyn after constituents who drive argued it would slow down their commutes.

Shahum said there are always tradeoffs.

“It’s about choosing whether public safety is actually the priority,” she said. “If you are not prioritizing that over other important needs like economic prosperity and the idea of speed then you’re not serious about safety.”