For nearly seven years, a small Georgia community has been haunted by the unsolved killing of 4-year-old Lun Thang, who was struck by a hit-and-run driver while she walked to school with a relative. Now, it's one of a growing number of small cities and towns that are winning major federal dollars to save lives like hers — and sharing the recipe for how they beat out bigger and better-resourced cities for the funds.

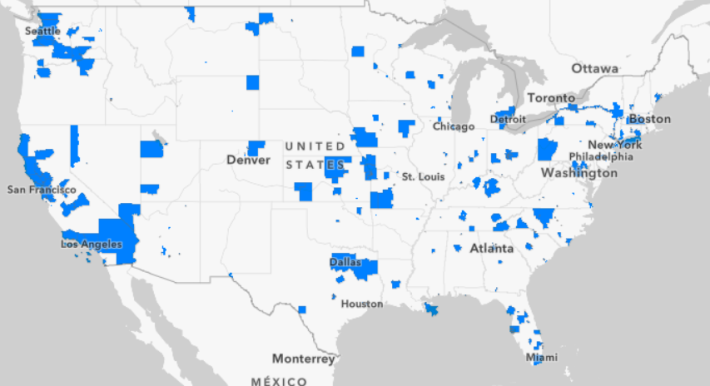

In early December, Clarkston, Georgia became one of 385 U.S. communities to win a Safe Streets and Roads for All grant, earning $1 million to develop a comprehensive street safety plan. That's an unusually large victory for a city of just 14,500 people with median incomes one-third lower than the national average.

And it could prove an unusually impactful one, considering that Clarkston has an annual traffic-fatality rate roughly double the national average — not to mention an unusually large refugee population, many of whom arrive to the United States without cars, jobs that pay well enough to buy them, or even the language skills necessary to read American street signs.

Known as both the "Ellis Island of the South" and "the most diverse square mile in America," Clarkston was identified as a good fit for international asylum programs in the 1990s, and by the 2000s, about half of residents were born outside the U.S. Students at local schools originally hail from more than 50 different countries — including Lun Thang, whose family emigrated from Burma, and whose story became the centerpiece of the city's grant application.

Translating that moving narrative into a funding victory, though, isn't an easy task for an under-resourced community. That's part of why Clarkston turned to the Local Infrastructure Hub, which offers cities under 150,000 residents the mentorship and resources they need to successfully compete for federal transportation money. In the most recent application round, participants in the Hub's "bootcamps" won 80 percent more funding than the average grantee, despite having less than one-third of the average grantee population.

"It turns out, this thing works," said James Anderson, head of the Government Innovation Program at Bloomberg Philanthropies, which co-leads the Hub. "The Cities signing up are smaller and often less well-resourced, and they’re drawing down bigger-than-average grants as a result of the technical assistance they’re getting. We’re really proud to be converting ambitions and dreams into winning applications and real safety on the ground."

Clarkston Mayor Beverley Burks credits the hub not just with helping her community win, but with empowering it to step up to the plate and make the case for why Clarkston's success is crucial to larger regional goals. One of the city's primary corridors, Indian Creek Drive, is a key route to county school and university campuses — including the elementary school to which Lun Thang was walking when she was killed. The 19-mile long Stone Mountain Trail also runs through its footprint, attracting countless Atlanta-area walkers and bikers every day.

"You have to be willing to invest in yourself as a city," Burks added. "You have to make sure you allocate the time to pull all the pieces together to make a viable case for why your city needs this type of safety plan. Having someone who had the skillset to be able to help write the narrative — that’s very crucial for the reviewers to understand the needs in your community."

The architects of the Infrastructure Hub are learning from cities like Clarkston, too — and using those insights to help more small cities win in Washington. Anderson says successful applications tend to display a handful of core characteristics, wielding qualitative and quantitative data to demonstrate why safer streets would translate to outsized community benefits, like economic development and poverty alleviation; they also tend to explicitly connect local safety efforts to federal priorities like the making America more equitable and combatting climate change. Truly standout applications also demonstrate cities' ability to pull together low-cost, creative financing options to secure local matches for federal dollars.

The best applications, of course, do all three — and a lot of Hub alums are hitting the jackpot. The tiny copper-mining hub of Globe, Ariz., for instance, successfully made the case for why a city of just 7,249 people deserved federal dollars to pilot a road-narrowing project which officials hope will lead to permanent improvements that have ripple effects for the region at large, which includes a major neighboring tribal nation; 6,137-person Gladewater, Texas, meanwhile, is improving infrastructure along a stretch of road where students have no choice but to walk to school in the street.

And as these stories continue to accumulate, Anderson hopes that advocates will hold them up as an examples for why street safety deserves even more federal money — especially in the small communities that need it most.

"We’re building the confidence of America’s small towns to put their hands up and apply for these dollars," he said. "When we started [the Hub], we sent researchers into these communities, and so many of them told us, ‘there’s no way we can ever win; this money wasn’t meant for small towns like ours.’ We’re creating proof points and showing what it looks like when small cities come home with these funds."