A few weeks ago, I accomplished a feat this phys ed dropout never thought possible: I reached 28 miles per hour on a bicycle.

To be clear, that's not a humble brag. I did it on a Class-3 electric bike which I'd borrowed from manufacturer Trek, mostly to find out what it feels like to ride a bike that can even go that fast — and one that's become become as much a symbol of the culture wars around e-cycling as an actual object with two wheels and a set of pedals.

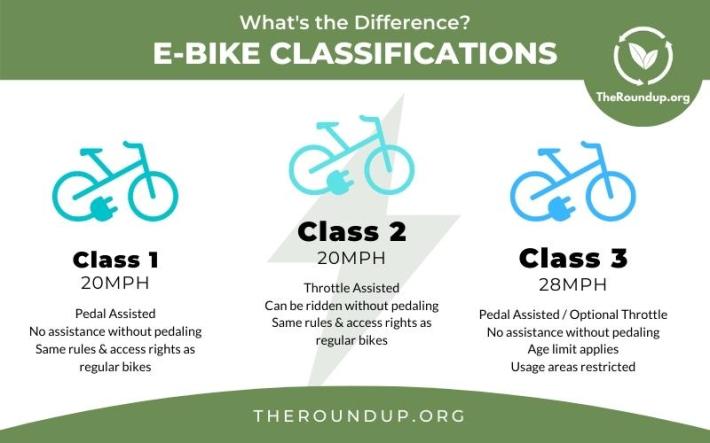

Before we get to that fracas though, let's go over some basics. The three-class e-bike system was developed mostly to help governments distinguish which types of electric cycles could (and couldn’t) safely be ridden on bike lanes, and what general e-bike characteristics were suitable (and unsuitable) for U.S. roads overall.

Within that system, a Class-3 e-bike is the fastest officially-recognized pedal-assist vehicle money can buy, with an electric motor which provides a speed boost only when the rider is moving her feet, up to (but not beyond) my new personal land-speed record. Designed primarily for long-distance commuters who aren’t carrying heavy loads, a Class-3 also doesn't typically have a throttle, which e-bikers tend to use to get a hefty bike moving from a full stop, rather than to keep a vehicle in motion like a moped. And if riders can rev their engines without pedaling, they still can't go above 20 miles per hour on throttle power alone. In some states, class-e bike riders are banned from sidewalks, bike paths, and trails and must stick to the public road, while in others, they're allowed in these off-road spaces if they can behave safely around other road users.

Otherwise, Class-3s look pretty much identical to Class-1 e-bikes, which usually are allowed on separated paths because they top out at 20 miles per hour — a speed that’s considered safe for mixing with non-e-cyclists. Class-2 e-bikes, meanwhile, are the same as Class-1s, but they can and almost always do have a throttle that works when your feet are still.

To the average Joe on the street, though, all these e-bikes tend to look pretty much the same— and if he has even the faintest idea what a Class 3 is, he tends to assume the worst.

Somehow conflated with both deadly-fast mopeds and slower, lower-class bike models, Class 3s, like all e-bikes, are covered by the mainstream media as a mobility monstrosity, balanced precariously on the line between human-friendly transportation and next-gen motorcycles.

And much like the illegal "e-bikes" that irresponsible manufacturers and users modify for dangerously fast speeds, some seem to treat the mere existence of a 28-mph e-bike as evidence that the mode on the whole is ultra-dangerous to manual cyclists and pedestrians alike, regardless of where — and how fast — any of those vehicles are actually ridden.

Of course, the idea of an extra-fast e-bike on a sidewalk should provoke anxiety — if Class 3s were actually permitted to ride there. Pedestrian danger does increase with vehicle speed, even if that speed is capped at 28 miles an hour and that vehicle is a 50-pound e-bike rather than a 5,000-pound truck. When ridden legally in the street, though, a Class-3 e-bike will rarely come anywhere near a pedestrian — and even if it does, the bike itself will rarely reach its top velocity.

"[We tend to ask], 'How fast can this bike go?' Well, how fast can our cars go — and how fast do we generally drive them?" said Ash Lovell, electric bicycle policy and campaign director for PeopleForBikes. "Just because a bike can go 28 miles an hour does not mean that you're going to feel comfortable doing that — and most people don't."

Unlike drivers in auto ads racing from zero to the top of the odometer with the flex of an ankle, Lovell explained, non-throttle e-bikes always require physical exertion from the rider — and typically, more and more of it as the bike speeds up.

I learned this firsthand on my own Trek test ride, which technically allowed me to achieve Tour de France-level speeds … but only for a moment, while pedaling as furiously as I could on a pancake-flat road. For the most part, going fast wasn’t just difficult; it didn’t feel natural in the places I tend to bike, except in a small handful of ultra car-dominated contexts when I was glad to have the extra boost.

When I checked my odometer at the end of the ride, I found I'd spent my time cruising around at 13 to 15 miles an hour, perfectly happy to reach my destination a few minutes faster without breaking a sweat.

To be clear, that's not a knock on the capabilities of the Trek Verve +4s, which is an objectively awesome, top-of-the-line bike that looks like the pedal-powered cousin of a Maserati. It's just that, counter to their speedy reputation, e-bikes of all classes and models actually tend to be ridden slower than manual bikes — and if anything, that lack of instantaneous, automotive-style pick-up is a good thing.

Where car commercials promise a total unity between man and machine, e-bikes actually deliver it: slowing down with you as you roll into a crowded park and react to the pedestrians around you, naturally accelerating to a comfortable clip when you speed up next to an impatient driver on a busy road. Moreover, class-3 e-bikes make their riders work a little bit for those faster velocities — as they should. In a city like mine, with virtually no bike lanes to speak of, it can be a great option, even if you only hit top speeds once in a blue moon.

After owning a class 3 e-bike for a few months, I think the class 3 ban on shared use trails is a nonsensical regulation. It is very easy to moderate the bike speed to that of a class 1. If pedestrian safety is the concern, just put a speed limit on the trail.

— multimodalalex.bsky.social (@MultimodalAlex) July 13, 2022

For regulators, though, the nuances of the Class-3 riding experience aren’t always apparent — and that can cause some big problems.

Last January, the Consumer Product Safety Commission stoked controversy when it refused a request from PeopleForBikes to "clarify that Class-3 e-bikes are considered bikes, not electric motorcycles," citing a since-updated federal regulation that defined a "low-speed electric bicycle" as a vehicle with a top speed of 20 miles per hour.

For now, at least, the CPSC functionally still regulates many Class 3s much like other e-bikes. Some advocates fear that if the agency didn’t, though, dodgy manufacturers of much-faster-than-20-mph, out-of-class "e-bikes" (read: motorcycles with pedals) could claim exemptions from CPSC requirements for safe batteries, brakes, and more, while further muddying the waters about the safety of real e-bikes in the public eye. And some are doing it already.

"The issue is that policy always lags behind technology," added Lovell. "And what we're seeing is that there's some gray areas in the regulatory space that are problematic in terms of safety."

As e-bikes continue to gain in popularity in the new year, Lovell hopes that the industry can send a clearer message to regulators and consumers about what Class-3 e-bikes can do — and how much good they can do if we can collectively move past the confusion.

"When all three classes of electric bicycles replace car trips, we reduce greenhouse gas emissions, increase people's health outcomes, and get more people outside," she added. "[We need to] help everyday Americans understand how to ride responsibly, how to purchase good products, and most importantly, how to keep this momentum going."