Sustainable transportation advocates across the country are taking action to physically remake streets for safety when city leaders fail to act quickly enough — and they're sharing resources with anyone who wants to join their ranks.

In a recent virtual event at the Vision Zero Cities conference, an anonymous panel of activists in three U.S. cities shared the "confrontational, illicit, and often illegal tactics" they use to make their streets safer and less car-dependent — while raising questions about why their governments aren't doing the same.

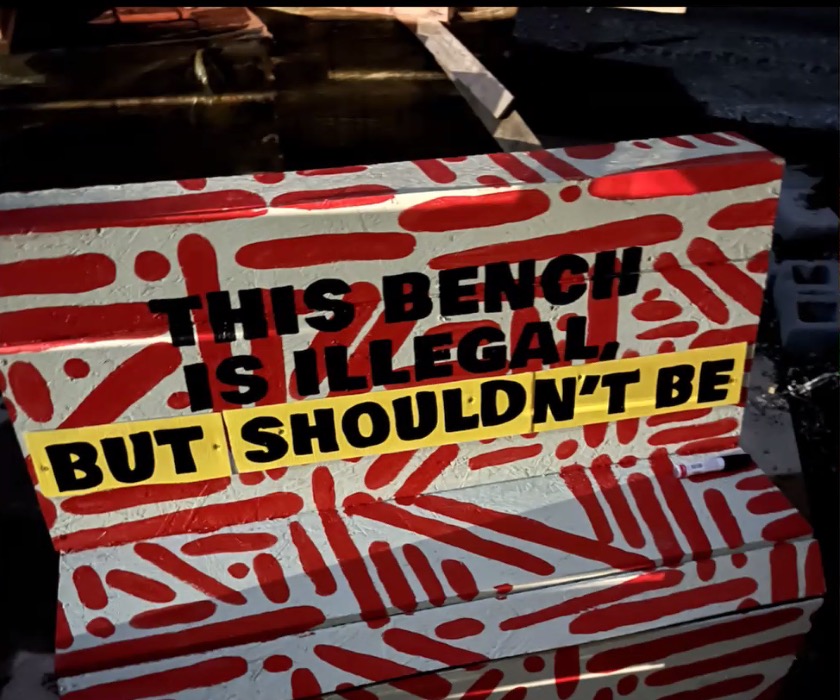

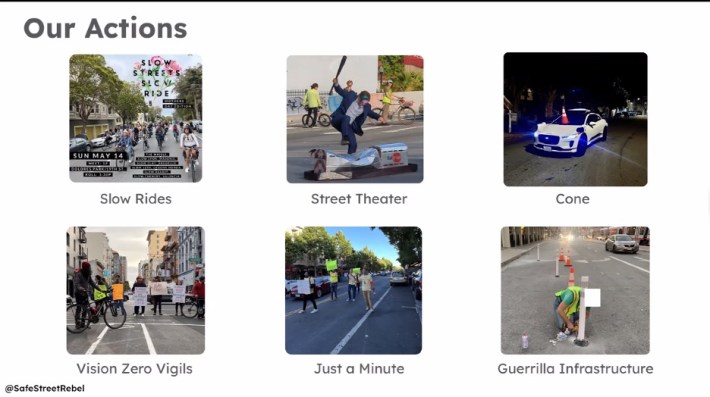

And those tactics are evolving quickly. Represented only by their organizations' respective logos to protect their identities, the panelists described a growing range of tactical urbanism strategies they've tried, including painting crosswalks and installing bus benches where their cities have provided none, stopping traffic to demand redesigns of dangerous roads, and even staging elaborate "street theater" protests of transit funding shortfalls, complete with a simulacrum of the California governor beating a cardboard train with a bat.

"It turns out that if you alert local news that you'll be blocking a major intersection imminently, they’ll dispatch multiple helicopters and make it the story of the day," laughed a rep from Safe Street Rebel, a San Francisco-based group that participated in the panel. "This created such a blunder for Gavin Newsom that the state filled the funding gap and he even signed the budget on a BART train. That was a huge win for us."

ICYMI @GavinNewsom is killing transit and we have only a few days to stop him. You can reach his staff here: (916) 445-2841. pic.twitter.com/n8B4ykfeZE

— Safe Street Rebel (@SafeStreetRebel) June 9, 2023

Most panelists said they chose direct action only after years of unsuccessfully lobbying for change through more traditional means — and watching their communities grew more deadly and car-dominated while they waited. And while taking matters into their own hands has sometimes exposed them to legal, personal and professional risks, they say doing nothing carries risks of its own.

"I thought, 'Well, what about liability on me?'" said an organizer from the Chattanooga Urbanist Society, who took it upon themselves to repair a destroyed a bridge railing next to a sidewalk that left pedestrians vulnerable to a 25-foot drop. "And then in that moment I thought, 'Wait — liability is already on me.'"

The response to these organizers' tactics, to put it mildly, has been varied.

Some cities have embraced their residents' can-do spirit; the Chattanooga group says they were recently nominated for an award by the mayor. Members of Crosswalk Collective Los Angeles, meanwhile say they've had to fundraise to pay police fines, even though they take pains to mimic official painting guidelines as closely as possible and act in response to community requests. Many of their DIY crosswalks have even erased by authorities, who often go on to install nearly identical crosswalks at those same sites — highlighting, in the process, just how farcical a bureaucratic approach to safety can be.

"With this kind of DIY urbanism, there is no such thing as a loss," added a representative from the Collective. "If we paint a crosswalk and it remains, then there is a little bit more safety for pedestrians. If it gets removed, well, then we have demonstrated the absurdity of the city's policies around safety and how they approach community involvement."

All three panelists stressed that participating in direct action doesn't have to involve risking arrest — or devoting countless hours and dollars to unpaid DIY road-work. While one advocate alluded to "a big, spicy group chat of 250" rabble-rousers scheming up their next moves, others say they operate with just a small core of carefully vetted volunteers who deliberately scale their involvement to whatever level their unique risk tolerance, resources and relative privilege will allow.

For some, that might mean donning a Gavin Newsom mask and stepping into traffic; for others, it means donating to mutual aid funds to help buy paint and traffic cones, without ever setting foot in the street.

"We keep us safe, whether the danger is from drivers, cops, or anything else," said reps for Safe Street Rebel in a follow-up interview with Streetsblog. "Our safety comes from our numbers and from looking out for each other. ... Even within an action, we often accommodate different levels of risk among participants. Handing out fliers, talking with interested neighbors, taking photos and video, making posters, and simply standing on the sidewalk holding a sign are all great ways people can contribute according to their preferences and risk tolerance."

All three groups also emphasized that their confrontational style of advocacy isn't a replacement for more traditional (and legal) types of organizing — and that guerrilla road crews certainly aren't a substitute for a good DOT. Ideally, though, direct action can speed along broader institutional reforms that mischief-makers can't easily accomplish alone, whether by expanding the public imagination about what streets can be, or simply passing around a petition at a protest.

"We may not be able to run our own bus line, but we did draw attention to transit funding shortfalls by blocking traffic," added the Safe Street Rebels. "We may not be able to get rid of every slip lane in the city, but we can show that it’s no big deal to get rid of one. Direct action can show what’s possible and bring hope. It can get other political processes unstuck by demonstrating alternatives to the status quo."

And if that feels a little disruptive, well, that's part of the point.

"As far as I know, radical change has happened never in history without some form of conflict or friction," said the Crosswalk Collective rep. "If, at the end of the day, we are able to raise awareness, and to bring up topics that people are not talking about, and to force city governments and people in general to talk about [street safety] — that's what moves policy. That's what moves society."

Even if minds aren't changed, at least they'll leave streets a little safer than when they found them.

"If the city wants to catch up and take a page from our playbook, we want to offer that to them," said the Chattanooga organizer. "We're never going to stand in the way of making permanent change. But we're just not going to accept the status quo."