Earlier this year, the Biden Administration announced the cities that will receive funds from the Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods (RCN) Program, a new series of federal grants that aim to repair at least some of the countless neighborhoods that were destroyed and divided by highways and automobile infrastructure during the 20th-century era of suburbanization. Created as part of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, the program directs $1 billion to study engineering solutions for the infrastructural scars that cut across so many American cities, segregating neighborhoods along lines of race and class.

One recipient is Buffalo, NY, for a cap over the Kensington Expressway, which was cut through the majority-Black East Side in the 1950s and paved over the neighborhood’s Frederick Law Olmsted-designed park. Others are Long Beach, CA, which is planning to convert a segment of I-710 into a more pedestrian-friendly boulevard, and Tulsa, OK, to study the removal of a highway segment through the Greenwood District, the famous “Black Wall Street.”

The solutions these cities are considering include capping over existing highways, rebuilding highways in new tunnels underground, converting highways to surface boulevards, and outright removal. While these strategies are potentially promising, they also risk perpetuating past mistakes and harming the very communities the RCN aims to serve. Previous attempts at implementing these solutions have had a mixed track record of success, reinforcing the dangerous automotive status quo on the one hand while serving as tools of gentrification and further displacement on the other. This is not to say these projects should not be pursued. Indeed, the RCN is a step in the right direction toward fixing the mistakes of the past. But in order to achieve the goal of reconnecting communities, it is important to scrutinize previous attempts at these solutions to learn from past errors.

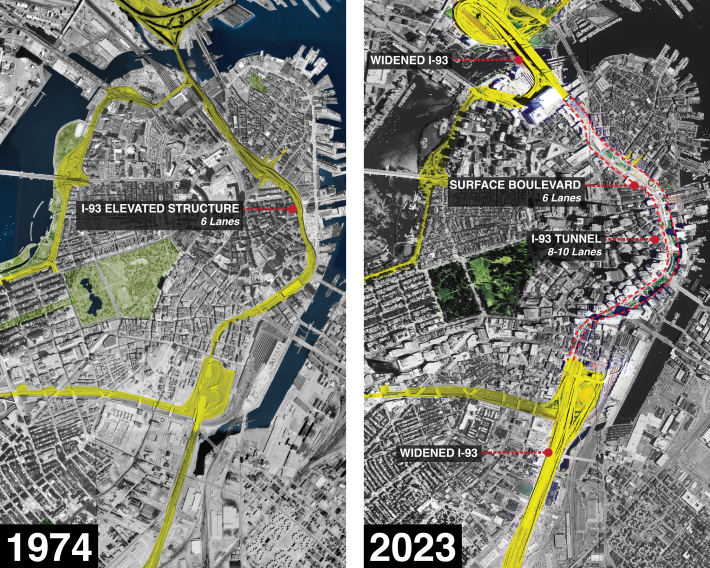

Boston’s Big Dig, of course, serves as a cautionary tale regarding tunneling and capping, demonstrating the fundamental flaw at the core of such a strategy. Seeking to accomplish two competing aims – easing traffic congestion and reconnecting the city’s divided downtown neighborhoods – the project ultimately failed to fully accomplish either.

Predictably, by replacing the previous six-lane elevated structure of I-93 with a ten-lane below-grade structure, the induced demand of additional automobile traffic from the project has led traffic levels and travel times to increase – in some cases doubling, as The Boston Globe reported shortly after the project opened in 2007.

Above the tunnel, the Greenway is certainly an improvement over the previous elevated structure. But by widening the highway beneath, the city doubled down on prioritizing suburban automobile access over the health and safety of local residents. The rate of pedestrian injuries around the project remains high, and Boston as a whole has some of the highest rates of pedestrian fatalities in the country.

Moreover, the shallow depth of the tunnel itself, combined with the myriad of offramps snaking their way to the surface, has left space for only a series of highly programmed parks dotted with pollution-spewing ventilation structures – as well as a surface “boulevard” with six more lanes of traffic on either side. Instead of knitting the city back together, the corridor continues to serve as a barrier, albeit a more aesthetically pleasing one.

Highway tunnels like the Big Dig or the more recent Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Tunnel in Seattle – which buried a section of highway while turning the former right of way into another wide surface road – are the product of the continuation of the same auto-oriented policies that built the Interstate in the first place. Since the mid-20th century, these policies have prioritized fast vehicle travel above all else, treating people walking, biking, or riding transit as afterthoughts.

While putting a highway underground can seem an intuitive solution to reconnect the communities above, because these same mid-century standards are still embedded in nationwide transportation policy, the reality is that such projects often become, at best, a form of “greenwashing” and, at worst, Trojan horses for further highway expansion. This is especially true when discussing older rights of way built before the adoption of present standards, where it is easy to cloak widening in the language of “modernization.”

Such modernization language has already been used to justify a potential widening of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, which cuts through some of the densest neighborhoods in the country. In the Twin Cities, a plan to cap over the highway that cut through the historic Black neighborhood of Rondo, St. Paul, would involve potentially widening the highway beneath, dividing local advocates.

For future caps like those being considered in Buffalo and The Bronx, leaders need to ensure that the addition of more lanes is not a part of the project. As happened in Boston, additional lanes will only induce further traffic, exacerbating automobile congestion while failing to address the safety and environmental impacts. A cap runs the risk of being an inadequate bandage over an even wider wound, one which induces further automobile traffic and worsens the underlying conditions that keep cities divided in the first place.

In short, the issue with capping and tunneling is that existing transportation policies – which are as deeply entrenched as they are severely outdated – encourage such projects to potentially become instruments of the very division that they seek to bridge. On the other hand, the issue with boulevardization and removal is that to date they have been used primarily as a tool of economic development – leading to gentrification and displacement – rather than as a means to achieve community reconnection.

Boulevardization, by reducing space for cars and slowing traffic to a more pedestrian-friendly pace, inherently holds more promise as an engineering solution than capping or tunneling. Boulevardization entails the complete removal of a highway structure and the replacement of the right of way with an urban boulevard, catered more to the needs of city-dwellers than automobile users. However, without proper implementation, boulevardization runs the risk of physically reconnecting a neighborhood, improvements which then encourage new development and gentrification, displacing the community they were designed to benefit.

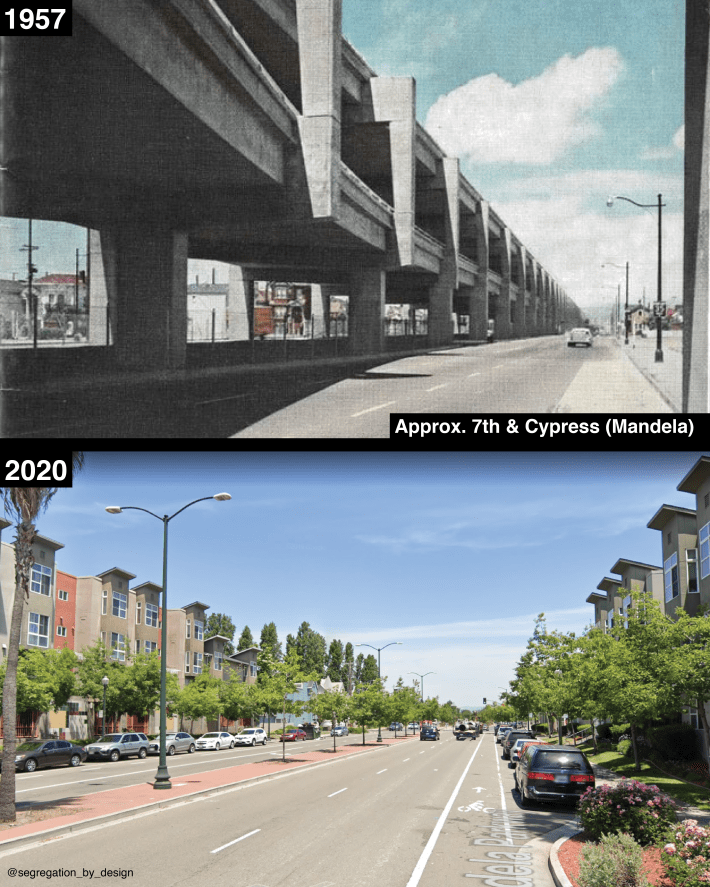

In the historically working-class, Black neighborhood of West Oakland in 1989, for example, the conversion of the Cypress Freeway Viaduct into the surface-level Mandela Parkway brought rising rents and higher resident turnover. A recent UCLA study found that between 1990-2010, median household income increased by 55% in the area within 250 meters of the parkway, compared with 35% of the rest of the neighborhood, and the Black population fell by 28%. Moreover, rather than completely removing the highway, the right of way was rerouted to wrap around the neighborhood and continues to spew pollution into the area.

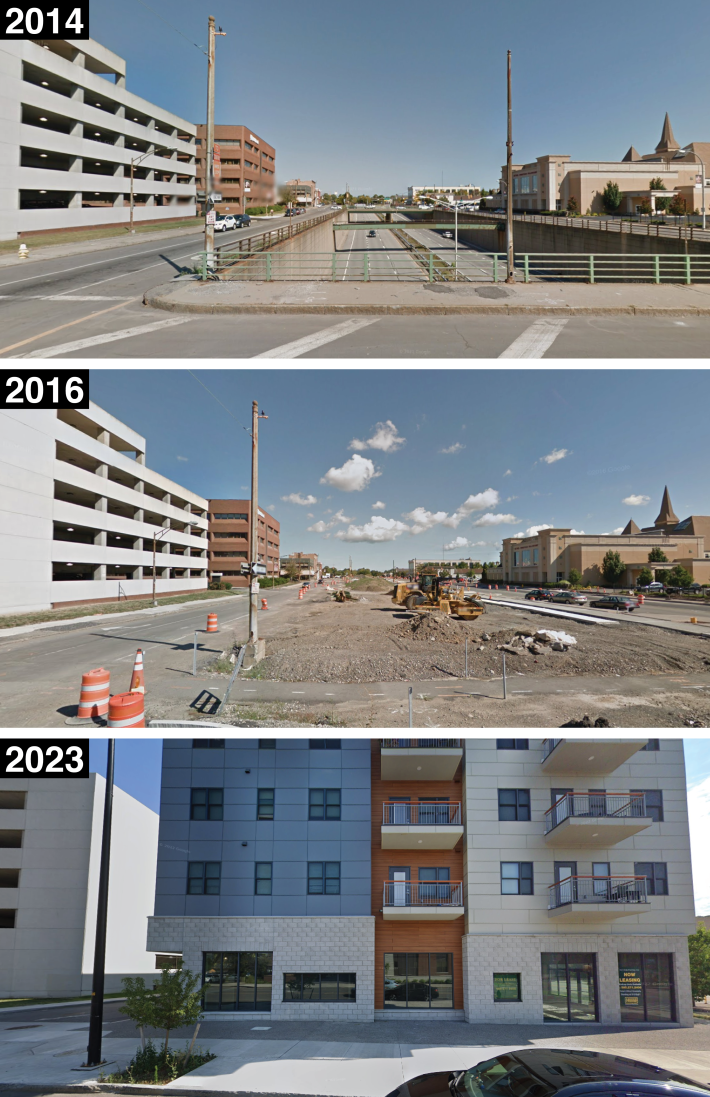

Unlike the previous cautionary tales, one project that holds initial promise is Rochester, NY’s Inner Loop removal project. In 2017, the city finished demolishing a portion of an elevated orbital highway separating downtown from the surrounding neighborhoods and replaced the right of way with infill affordable housing development. City officials have adopted a reparative approach, attempting to limit displacement while promoting regrowth.

"Equity is huge on this," said Erik Frisch, special projects manager for the city, speaking to the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. "This is not just transportation. This is not just community development. It is focused on racial equity and healing old wounds and making sure that current residents and residents that were displaced will benefit."

In addition to Rochester’s example, recent scholarship from the National Institute of Health and advocacy organizations has focused on developing anti-displacement strategies that could counter gentrification's negative effects. Such strategies fall into the categories of preservation, neighborhood stabilization, inclusive development, and more. For the cities receiving funds from the RCN to be successful, they should incorporate these tactics and look to Rochester’s example.

However, to truly reconnect communities, highways need to be addressed as larger parts of a flawed transportation system that disproportionately funnels traffic through non-white and poor neighborhoods, bringing pollution and noise, making local trips more difficult, and killing and injuring Black and brown residents. This means finding new solutions and moving away from policies that prioritize automobile movement at the expense of other, more equitable modes of passenger travel (such as public transit, walking, and biking) and more efficient modes of freight travel (such as rebuilding local freight rail, maritime distribution, and local distribution hubs).

Unfortunately, the RCN does little to address these underlying issues. While the RCN pledged $1 billion towards addressing the harms of highways, the rest of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act made over $273 billion available for highway expansion projects.

Given this overwhelming reinvestment in the status quo, despite the warnings previously discussed, it is important not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Feasibility matters. While the solutions being discussed may not be ideal, if properly implemented, they can at least begin to move things in a better direction and improve local conditions. As planning in these cities begins, incorporating the lessons learned from past projects will ensure that future ones aren’t one step forward, two steps back.