A proposal to tear down a Minnesota highway that's devastated Black and low-income communities for generations is officially back on the table — and fueling a heated debate among advocates about whether it's actually possible.

In mid-July, the Minnesota Department of Transportation rolled out a slate of 10 design alternatives for the future of a 7.5-mile stretch of Interstate 94 that runs between Minneapolis and St. Paul, including two options that would bring the highway to grade and convert it into a boulevard, which won the most community support in early public meetings.

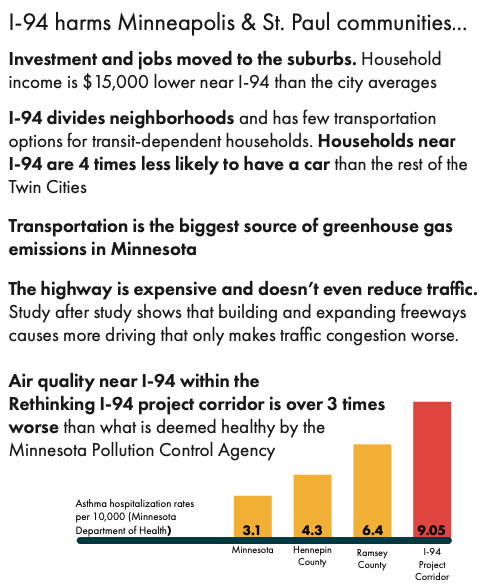

That came as a pleasant surprise to some local advocates, many of whom have been told for years that Minnesota's most-used freeway was an unlikely candidate for a full-scale teardown. For local non-profit Our Streets Minneapolis, though, thoroughly reimagining I-94 isn't just the best option on the table — it's the only option if the Land of 10,000 Lakes truly wants to reckon with the racist legacy of its transportation choices.

"I would argue that it isn't bold at all to think about affording these communities the same quality of life that has been afforded to white Americans for generations," said José Antonio Zayas Cabán, the group's executive director. "It's really more just about catching up to historic racial inequities and intentional racial targeting, as well as the disruption of opportunity for black Americans to generate wealth across generations."

'Removing the highway is not radical'

The team at Our Streets isn't just fighting to get MnDOT to accept an at-grade option over the eight outlined alternatives, all of which would either retain or even expand the highway. They're fighting to overhaul the two "imperfect" conversion proposals in favor of a more ambitious concept they're calling Twin Cities Boulevard, which would incorporate subways, extend a major greenway, and expand the project area to include other adjacent highways that the group says would be ripe for repurposing if I-94 were removed.

And they say those ideas came directly out of the on-the-ground conversations they've had with corridor residents who never accepted the idea that the freeway was there to stay.

"We built an amazing grassroots organizing team with some really talented canvassers that go out and have individual conversations with residents that experience the highway every day," said Alex Burns, Our Streets' advocacy and policy manager. "And to those residents, removing the highway is not radical; [they think it's] actually really interesting and exciting to think about something else being in their neighborhood, other than a loud, noisy polluting [road.]"

'Band-Aid' solutions and 'pretty pictures'

That vision, though, isn't shared by everyone in the Twin Cities – mostly because some don't believe it's possible.

For more than seven years, some residents of the I-94 corridor have been organizing support for the Rondo Community Land Bridge, a 16-acre cap that would leave the highway intact, but establish a cultural enterprise district aimed at restoring intergenerational wealth to African-American Minnesotans atop it. Named for a historically Black neighborhood that was bulldozed to make way for the highway, the project won a $2-million federal Reconnecting Communities grant to study and plan the project, which its supporters say is more realistic than the Twin Cities Boulevard.

"They’ve been trying to compare their idea to ours in order to elevate their own," said Keith Baker, executive director of Reconnect Rondo, which is spearheading the effort. "[Our Streets MLPS has] not really done any studies that say that the boulevard would be good for the community of Rondo — and we have multiple studies that say this will benefit them. When they're able to produce a specific, definitive study that says this will be good for the residents of Rondo, the descendants of Rondo and the city on the whole, I’d be open to hearing more. But right now, they don’t have anything more than pretty pictures."

(Editor's note: shortly after the publication of this article, Our Streets Minneapolis announced that they are "funding independent studies of a boulevard conversion on I-94" in partnership with Toole Design group, Smart Mobility, and other groups.)

Zayas Cabán, though, says MnDOT's new boulevard alternatives send a clear signal "that the work that we've done to organize and inspire community members expand their imagination, work on feasibility and plausibility [is working]" — and that no U.S. community should accept the idea that urban highways have to stay, whether they have studies in hand or not.

Burns stresses that because highways only reach the end of their useful lives every 50 to 60 years, "band-aid" solutions like land bridges can extend inequities for generations — or at the very least, miss a major opportunity for reparations. He cites a new highway cover that was recently built over I-70 in Denver, which made space for a new soccer stadium and a community park, but at the cost of residents' homes, the addition of two more lanes of vehicle traffic, and all the emissions, traffic violence, and other negative externalities that come with it.

"Yeah, it's definitely a nice neighborhood amenity — but is playing soccer on top of a freeway a good idea?" he added. "And did it fundamentally change the economic, public health, climate, transportation access and racial inequities that the surrounding neighborhood was facing? Probably not."

"In our view, rebuilding the highway and capping it is sort of a sending a second message to another generation of children that we still do not think that Black Americans, and immigrants, and people of color, merit the same quality of life that White Americans already enjoy," Zayas Cabán added. "The motive there isn't the community; it's continuing to find a way to rebuild the highway. And if we think of the highway as an emblem of white supremacy and racial injustice, then we shouldn't be thinking about whether or not it's feasible [to tear it down]; it's just the right thing to do."

Baker, who is Black, says feasibility does matter — and that the land bridge is what the Rondo residents really want, based on his group's community engagement. And he also says his obligation is to the Rondo community, unlike Our Streets, which bills itself as "a local nonprofit working for a city where biking, walking, and rolling are easy and comfortable for everyone."

"When it comes to reconnecting communities to movement and opportunity, who leads matters," he added. "The people who have been devastated by the freeway system ought to lead. While [the Twin Cities Boulevard] might be good for one community, it doesn’t necessarily mean it fits another."

Keep pushing

One thing both advocacy groups can agree on, though, is that like urban highways in virtually every city in America, I-94 has had a catastrophic impact on the Twin Cities' most marginalized — and its next chapter must be a catalyst for change. Both say it's imperative that any new land freed up by reimagining the road be dedicated to a community land trust, where it will be used to reparate Black and brown communities by restoring opportunities for them to become business owners, homeowners, and residents of tight-knit neighborhoods that center their needs.

The only question is how they'll get there, if either proposal can win — and what example they'll set for other U.S. communities if they do.

"Sometimes I get asked by people that maybe aren't directly impacted by the highway, 'what is the compromise solution that you're you're willing to accept?'" Burns adds. "But we don't believe that, as a nonprofit organization, we have any ability to negotiate such a compromise. Our intention is to continue pushing for the best possible outcome, and we really think that it's possible that Minneapolis and St. Paul can set the standard for for other cities across the country to follow."