Editor's note: a version of this article originally appeared on Next STL and is republished with permission.

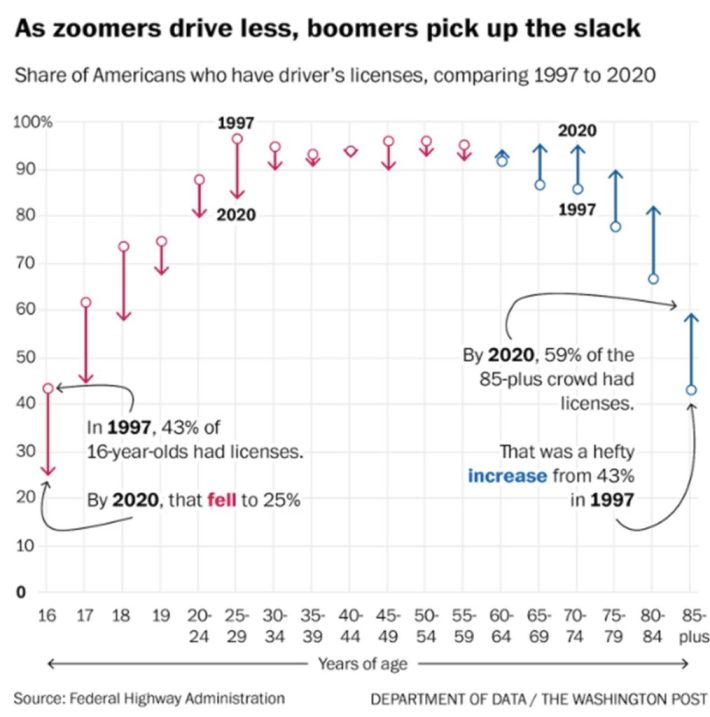

America is getting older, and American drivers are getting way older. This sea change in the demographics of those operating motor vehicles is incredibly important — and, I would argue, under-considered in the urbanist world.

Older adults driving in complex environments — think complicated traffic patterns, lane changes, turns, and congestion — have a much higher crash risk than the average driver. Older adults are also far more likely to die when involved in an automotive crash due to preexisting comorbidities. The risks associated with driving affect not only these older drivers, but everyone around them.

I study Alzheimer’s Disease at Washington University in St. Louis. One of our ongoing projects is a naturalistic driving study called DRIVES, led by Ganesh Babulal. Participants in the DRIVES study are enrolled in research at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC) and consent to having a small data logger very similar to the Progressive Insurance Snapshot Program placed in their car. Through their participation at the Knight ADRC we collect blood, cerebrospinal fluid, MRI/PET images of their brains and perform cognitive testing. Through their participation in the DRIVES study, we also get information sampled every 30 seconds of their lat/lon coordinates and driving speed.

Alzheimer’s Disease is a slowly progressing neurodegenerative disorder. Although (sadly) many of us are familiar with the “clinical manifestations” of this disease – forgetfulness, difficulty with navigation, and progressive decline in cognitive functioning — this disease actually begins 15 to 20 years prior to when those observable symptoms begin to manifest. By then, things called “amyloid plaques” are already developing in the brain. The presence of these plaques can be detected with appropriate PET radiotracers, isolated from cerebrospinal fluid, and – as of relatively recently – with blood.

Prior research has established that cognitively normal drivers with amyloid plaques in the brain exhibit many changes in driving behavior, including less-aggressive driving behavior, smaller driving space, less seatbelt use, late responses to changes in the driving environment, more driving errors on road tests, and reduced driving speeds. Driving behaviors are so characteristically modified by the presence of amyloid plaques that one of my colleagues was even able to predict whether or not someone had amyloid in the brain solely from their driving data.

Driving is an incredibly complex task. You have to deal with constantly changing stimuli, adjust to dynamic conditions, engage in navigation and planning, and just generally try not to kill anyone around you. For people with amyloid plaques gunking up their brain, this is particularly hard. The average older adult actually stops driving roughly seven years prior to death, and while hanging up the keys may seem like a positive for road safety, this results in lower social participation and increased isolation and depression.

So what is our plan for older drivers? If older adults are not getting out of their cars — which, given current land use policies, they kind of can’t — shouldn’t we be curious about what the effect of complete streets will be on the aging driver?

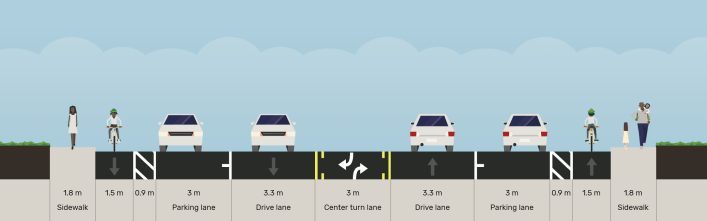

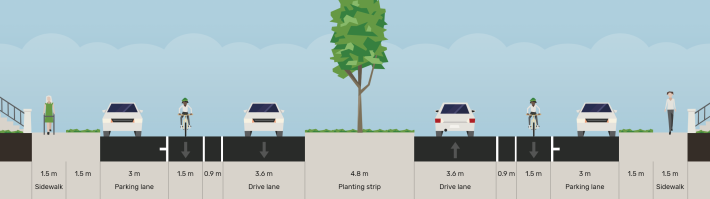

So that’s what we set out to do. As a natural experiment, we looked for instances where road diets had been implemented in the St. Louis region at some point during the DRIVES study (2015 – present), focusing on road segments where a relatively large number of research participants had driven.

What we found was kind of amazing.

Overall, implementing road diets resulted in slower speeds on each of the three streets. We also observed a pattern consistent with the literature: prior to road diet treatment, drivers with amyloid plaques in the brain drove more slowly than drivers without.

What was surprising, though, was that implementing a road diet caused the healthy, amyloid-free drivers to slow down but there was no additional slowing of the drivers with amyloid plaques — because they were already traveling slowly to begin with This differential effect was unexpected, but may help explain why road diets are so frequently associated with major decreases in car crashes: the design of the road forces all drivers to a consistent speed.

Put another way: After a road diet, all motorists seem to drive at a rate that feels comfortable to a mildly-impaired older adult.

This finding set up the conclusion of our paper: [Road diets] could empower older adults to continue driving while maintaining the safety of other road users both inside and outside of vehicles. Given the current state of the United States’ auto-dependency, lane repurposing could translate into much higher quality of life for older adults without sacrificing the safety of the individuals around them. We recommend that policymakers consider lane reduction solutions to facilitate older adults’ ability to age in place.

As a person who predominantly travels by bike, I am a big fan of road diet elements like parking protected bike lanes, and I would love to see more of those throughout my city. I felt that way before I studied them, but after considering the problems associated with an aging populace through an academic lens, I am an even bigger fan.

Read the full study, Differential Impacts of Road Diets on Driving Behavior among Older Adults with and without Preclinical Alzheimer’s Pathology, in Transportation Research Part F.