Civil engineers play an “outsized role” in designing transportation systems and undermine public safety — and to prevent theepidemiologic problem of traffic injuries and deaths, public health officials need to get more involved, a new report argues.

There is, of course, a growing understanding of the scope of the problem in a nation where roughly 42,795 were killed in crashes last year — a figure so alarming that federal Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg called it a “national crisis.”

But not enough systemic change is being made, according to the authors of the new report, “The Safe Systems Pyramid: A New Framework for Traffic Safety,” published recently in Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives.

“Engineers and planners are the people that are doing public health work,” said the study’s lead author David Ederer, who added that the current hierarchy doesn’t make roadways safer because officials don’t really understand what causes injuries in a crash.

“People don’t cause injury,’ Ederer said. “It's the amount of kinetic energy transferred from one body whether it be a vehicle or a sidewalk, or the roadway, to the human body, which can only sustain a certain amount of force transfer.”

So traffic safety isn’t about individual drivers but about the larger public health system.

“We need to act at the population level to expose as many people to safety as we can,” Ederer said. “The best way to really create a safer, healthier world is to change the context in which we live. So the associated economic factors that influence our risk every day are really important.”

A new paradigm

The report advances a “safe systems pyramid” and argues that public health officials’ role in Vision Zero needs to change from mere data collection and evaluation to actually applying public health concepts — such as the notion of prevention — to traffic safety.

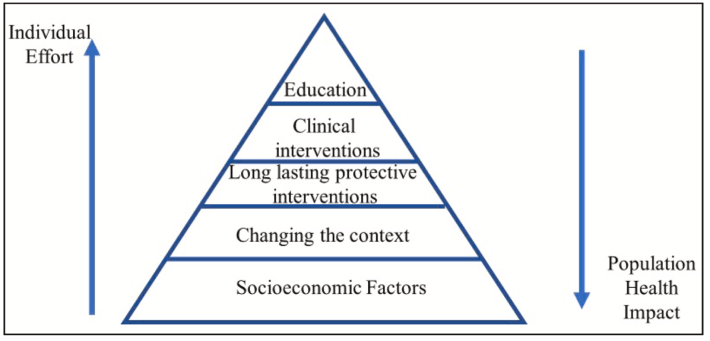

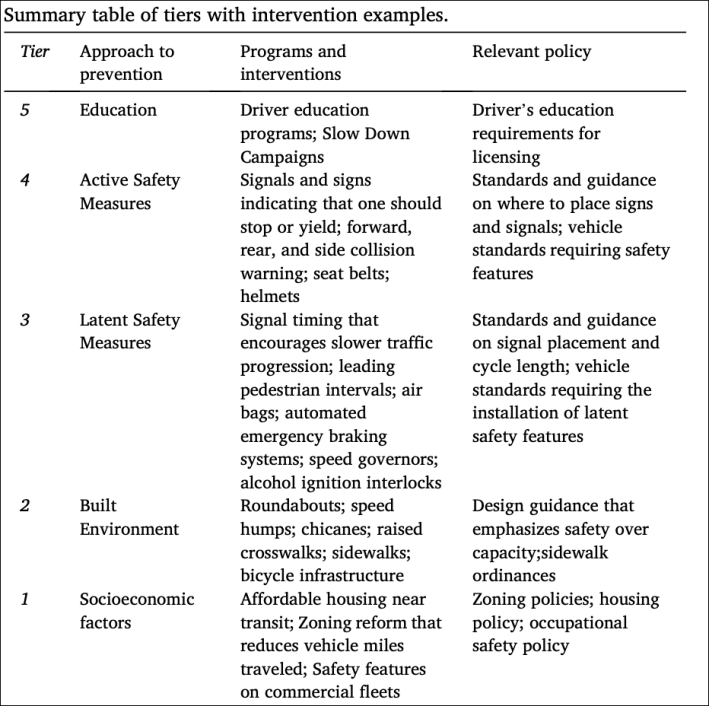

The new pyramid looks at issues from a public health perspective, zeroing in on larger population issues that could make a significant difference.

For instance, the bottom of the pyramid are the socio-economic factors that play a larger factor in how people get around, and how much time they are exposed to larger kinetic energy.

“If housing gets more expensive in the middle of a city, it means people have to move further and further outside that city center, and they have to travel further, “ Ederer said, “And that means they're exposed to the risk inherent in the transportation system for a longer period of time.”

The built environment is next on the safe systems pyramid once population and socio-economic factors come into play. “We want to create spaces where the potential amount of kinetic energy transferred in the event of a crash, because they're going to happen, is low,” Ederer said. This means separating cars from pedestrians and cyclists as much as possible, and also creating systems that can slow down the potential for high energy collisions.

A traffic circle is an example of how the built environment can be used to increase safety, Ederer said.

“Roundabouts fundamentally alter the direction of a crash and the speed at which it happens. So that's a very good built environment intervention, because that works on the level of altering the amount of kinetic energy transferred,” Ederer said.

The safe system pyramid provides a new way to look at old problems, but the solutions can be limited if both planners and public health practitioners don’t take on traffic safety. There is growing recognition of the need for public health practitioners to work with planners and engineers, but the success stories are harder to find.

A slow road to intersectionality

Individual groups use public health methods to get their message across, but it’s rare to see public health agencies leading the charge. And there may be some real world reasons for that.

“We're seeing more public health officials understand how important it is to prevent chronic diseases, [like traffic violence],” Ederer said. “But man, it's hard. They're they're not funded. One highway project probably exceeds many, many departments of health, yearly budget.”

On a national level, the CDC issued recommendations way back in 2010 for improving health through transportation policy, such as by promoting active transportation, expanding transit and creating better-designed streets.

Ederer cited the CDC’s Active People, Healthy Nation program as a way to intersect public health and reduce traffic deaths, but merely recommending active health isn’t enough.

“Our primary strategy is using community design to create activity friendly routes to everyday destinations,” Ederer said. “[But] no one is going to be able to walk or cycle if they don't feel safe while they're doing it.”

Back to the future

The report also reveals that there was so much more collaboration between engineers and health officials in the past.

“There's a long history of engineers in public health,” Ederer said. “ Public health engineering was a field back in the 1920s. We kind of got away from our roots and I want us to get back to it. That's why I do what I do.”