Utah is testing a first-of-its-kind technology that will automatically calculate the amount drivers should pay for their hyper-specific daily driving habits — and spark difficult conversations about how much we’re willing to charge them.

Last month, the state of Utah announced that it will pilot a new GPS-equipped dongle that will not just monitor how much motorists drive, but exactly where they do it, down the specific lane on the highway they choose. Then, communities can consolidate that data into a single road usage charge that can be automatically adjusted based on their unique priorities — think extra tolls for using the express lane, or graduated fees for low-income motorists who truly have to drive — and automatically distributed to the agencies that manage the exact roadways those drivers’ actually traveled. That dongle data, in turn, will be validated against the universe of other surveillance sources currently collecting data on pretty much everything drivers do, like their cell phones, on-board vehicle technology, and traditional roadside cameras.

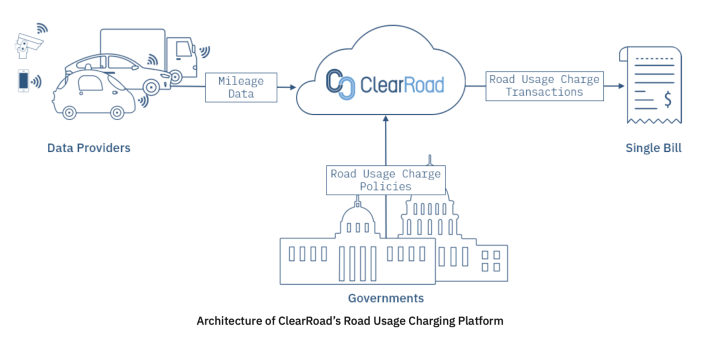

The program, which will be operated by Brooklyn-based transportation startup ClearRoad, is being billed as the next evolution of the long-sought “vehicle miles traveled” (or VMT) fee, which the U.S. Department of Transportation will soon begin studying as an EV-friendly alternative to the gasoline tax nationwide. Unlike the company’s earlier VMT experiments in Oregon and Bogotá, though, ClearRoad execs say the technology has gotten so mature that governments may soon be able to start thinking about bringing all of their driving fees onto a single bill via a device embedded directly in cars, rather than charging motorists separately at the gas pump, the toll booth, the congestion pricing camera, the DMV, and so on.

“There’s no technical limitation to this,” said Frederic Charlier, CEO and co-founder of the company. “It’s more about [a series of] political and social decisions that the community needs to make. What pricing is fair? How should we distribute the costs of transportation? Who is benefiting from the status quo, and who is actually subsidizing others? The beauty of it is that anything is possible; the technology enables any type of vision about what ‘fair’ means.”

Even under our current system, though, those questions remain among the most hotly debated in American politics.

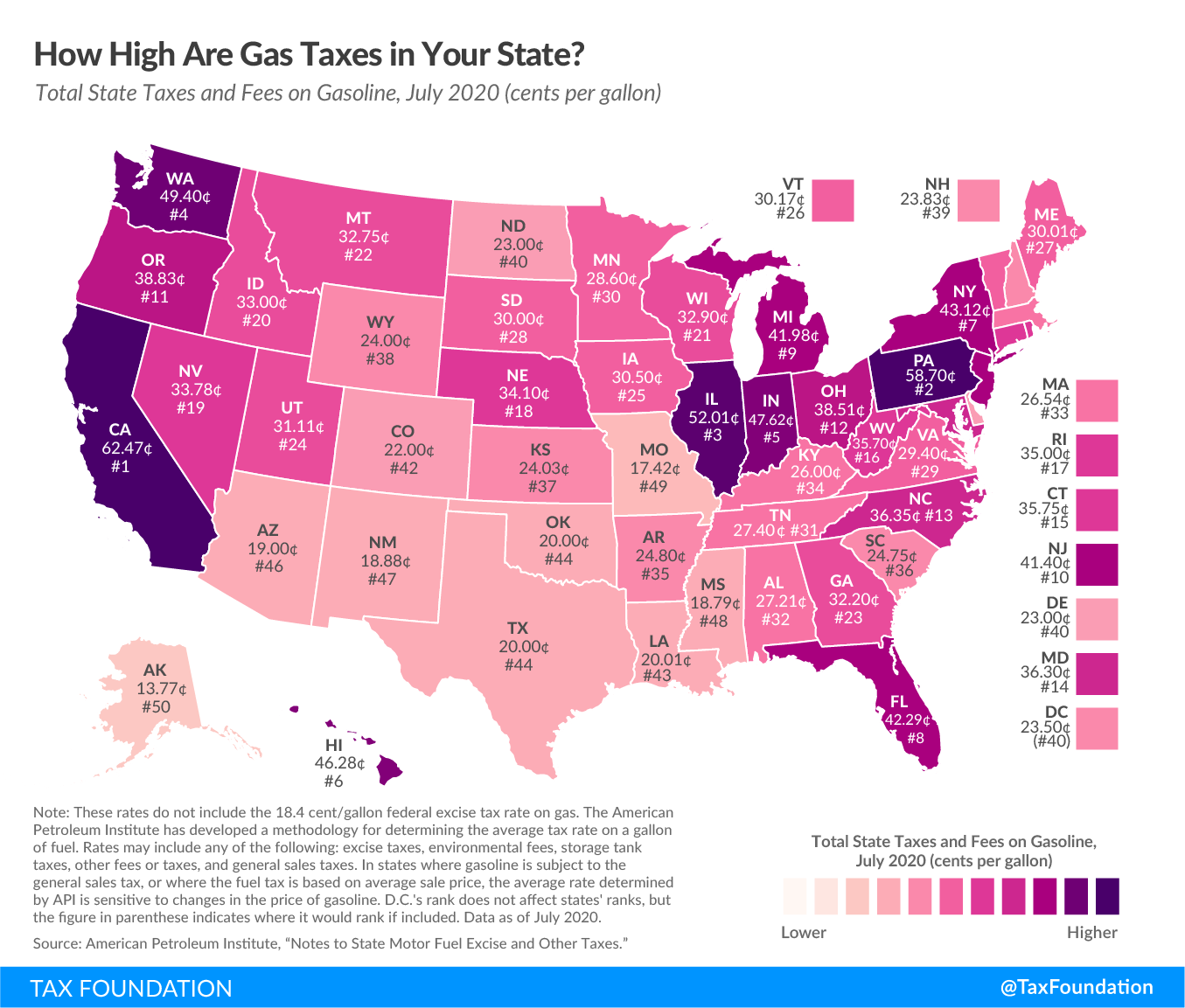

Thanks to perennial pressure from drivers, the federal gas tax has remained stuck at just 18 cents a gallon for 30 years, losing about 70 percent of its buying power in the years since while European fuel taxes soared to an average of about $2.40 per gallon. Meanwhile, even the highest state gas taxes in the country haven’t risen either, and other driving taxes and fees have failed to fill the gaps, prompting virtually every level of government to siphon money off of taxpayers’ general funds to keep roads and bridges from crumbling — or, too often, to keep building more highways even as roads and bridges crumble.

Today, the Institute on Taxation and Economic policy says that “taxes and fees paid by drivers … now make up a smaller share of total highway funding than at any point since the Interstate Highway System was created in 1957” — a percentage that’s only set to fall with the increased adoption of electric cars and accompanying decrease in gas tax revenues, which make up the single largest road user charge America has. And worse, because driving taxes and fees are atomized across the entire transportation system, motorists tend to think they’re being nickeled and dimed at every turn, even though they’re actually being subsidized by people who don’t or can’t drive at all.

“When you ask most people, they will overestimate how much they actually pay for roads directly,” added Charlier. “If I’m not mistaken, [road user charges make up] under five percent of the cost of owning a car; you pay much more for the insurance on your vehicle, or for replacing your suspension, than you actually pay for the roads you drive on. Trying to make sure that every level of government will have sufficient funds to continue to maintain road infrastructure will be challenging with this transition [to electric cars]; we already have all these questions about the existing system and how the money is being split among the different government entities. This pilot can give a better understanding of how the money could be managed, and how this technology could enable us to have funding for everyone.”

Charlier is careful to note, though, that could is different than will. Even if most U.S. drivers get past privacy concerns about equipping their vehicles with hyper-accurate GPS dongles and the dizzying network of high-tech eyes that are already watching them, they might fight back against being charged more for entering a busy downtown at rush hour, as New York City’s long, messy congestion pricing fight has illustrated all too plainly. In other states, governments might look at data collected from ClearRoad technology and decide that certain drivers should get even more subsidies than they do now, particularly in rural areas that are heavily dependent on cars — even if those drivers are wealthy exurbanites who simply choose to live fuel-intensive lifestyles, rather than, say, farmers.

Other governments, though, could theoretically someday use ClearRoad technology to create road usage charges that disincentivize unnecessary or dangerous driving. Some cities might charge the owners of over-sized SUVs more for every mile they drive within their borders to compensate for the extra damage they cause to roads (and the bodies of pedestrians they strike); others might use VMT data to give discounts to low-income drivers who truly have no choice but to schlep across town to multiple, far flung jobs, and direct their taxes and fees towards building better transit. And considering that states as diverse as blood-red Utah and bright-blue Oregon are experimenting with advanced road usage charging, even more applications of the tech are almost certainly still waiting to be discovered.

“At the end of the day, my experience tells me we should go step by step,” Charlier added. “And I think that that’s what the states are doing. Right now usually, we pretty much only have one rate. What if, maybe, we had two or three of four rates — and then from there, maybe move to even more complex systems?”

The post Utah’s ‘Road Usage Charging’ Pilot Could Finally Price the Roads Properly appeared first on Streetsblog USA.

The post Utah’s ‘Road Usage Charging’ Pilot Could Finally Price the Roads Properly appeared first on Streetsblog New York City.