Black pedestrians, bicyclists and micromobility users are subjected to a far wider array of dangerous laws than many sustainable transportation advocates may realize, a new report finds — and repealing them alone is not enough to guarantee them the freedom of mobility they need and deserve.

In what may be the most comprehensive analysis of laws aimed at vulnerable road users to date, researchers at the firm Equitable Cities scoured the roadway rules in all 50 states to identify "policies that evidence shows are being enforced in a racially discriminatory manner, or that have strong potential to be enforced in a racially discriminatory manner," specifically against Black U.S. residents who walk and roll.

That data was accompanied by moving interviews with a diverse group of Black road users about how those laws affect their lives and the ways they move through their cities — something that's deeply personal to lead author Charles T. Brown, who coined the "Arrested Mobility" framework (and eponymous podcast) to analyze the many reasons why access and opportunity remain out of reach for so many Black Americans.

"You have this feeling that you're being watched, even when you're not doing anything wrong," said Brown. "[You feel like] you're being policed differently, or could be policed differently at any time. ... I wanted to make sure that you felt these people's pain, their emotions, and that you saw that, [no matter where they fall on the spectrum of] the beautiful rainbow that is Black, that they are still suffering similarly to their peers."

Those feelings are not just subjective and individual. Throughout the report, Brown and his colleagues cite a massive body of research that shows Black road users throughout the U.S. are significantly more likely than White road users to be policed for mobility-related infractions, to face violence and death at the hands of law enforcement when they're stopped, and to live in communities that rely on fines and fees to support their municipal budgets, even though Black residents disproportionately struggle to pay them.

And when it comes to sustainable modes, many of those stops happen under the pretense of policies that are supposed to keep people safe, but in practice, can actually endanger them — if they can realistically follow them at all.

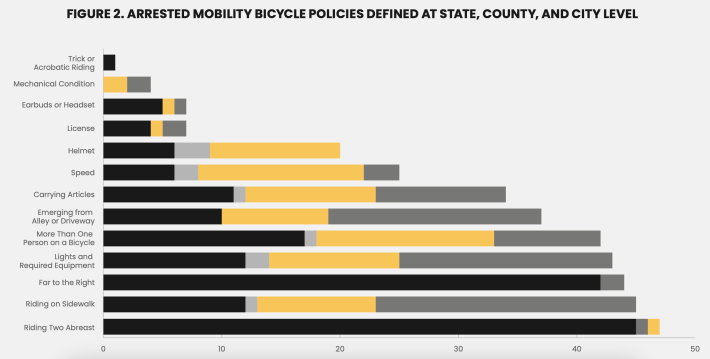

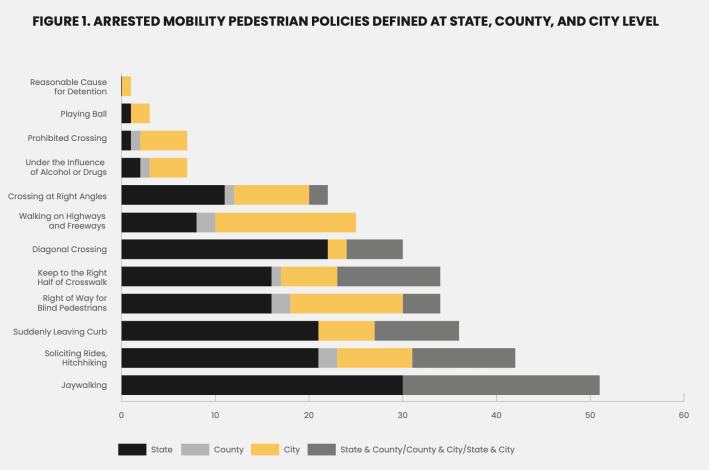

The researchers found, for instance, that 82 percent of U.S. states make some provision against walking on highways or freeways, even when communities are so divided by autocentric roads that pedestrians have little choice — a situation that's all too common in historically Black communities through with the interstate highway system was largely routed. Another 64 percent have laws prohibiting the operation of bikes on sidewalks, even when the roads that run alongside them have no bike lane and a steady stream of dangerous, fast-moving cars — road features which, once again, are disproportionately common in Black neighborhoods.

And when the researchers looked at the two largest cities within each state, they found a trove of even more troubling laws — many of which leave officers wide discretion on when they should be enforced.

Those included not just prohibitions against "jaywalking" outside of a crosswalk that might not exist or be easily available, but prohibitions against walking specifically on the left side of that crosswalk when you do reach it; "suddenly leaving the curb" for any reason a officer deems unacceptable; children playing ball on the sidewalk, even if they have nowhere else to play; biking with headphones on, even as drivers blare by with loud stereo systems; biking with an object that police deem to be too unwieldy to handle safely on two wheels; pedestrian "assemblies," or the simple act of walking with a group of friends an officer decides is too large; and biking or walking under the influence of drugs or alcohol, even as an alternative to drunk or drugged driving.

And because the researchers only had the resources to look at 100 large cities and a handful of counties in the U.S., that long list isn't exhaustive.

"Many of these laws are very archaic, they're outdated, and they simply don't achieve what they're intended to achieve, which is the health, safety and welfare of people on our streets," Brown adds. "Instead, unfortunately, they're leading to more discrimination, more harm, more violence against people of color."

Brown stresses that while repealing problematic laws, decriminalizing common roadway behaviors, or shifting to automated enforcement methods that leave less to individual police discretion can all help, the mobility of Black U.S. residents depends on more than those simple reforms alone. The report authors made additional recommendations, including:

- Embracing dedicated infrastructure for vulnerable road users, not just as a tool to end traffic violence but a tool to prevent criminalized behavior like sidewalk riding and jaywalking and reduce the need for human enforcement

- Reducing or eliminating court fines and fees associated with pedestrian, bicycle and e-scooter policies, and remove a key incentive for municipalities to rely on those fines to make their budgets

- Writing laws that prohibit police from using minor vulnerable road user infractions as a pretext to investigate them for more serious offenses

- Engaging the bicycling industry to sell cycles with headlamps, bells, and other key safety equipment built in, rather than passing policies punishing people for not buying that equipment separately

The researchers' final recommendation, though, may be the most important of all: that transportation leaders to analyze and address all the structural reasons why Black people experience arrested mobility anywhere they move. And that includes not just a deeper, ongoing analysis of problematic roadway laws, but more data on how they are enforced, what safety and individual impacts they create, and how these problems are mirrored on every mode, everywhere.

"This [work] is the thematic, not just episodic," Brown added. "We focus on arrested mobility within the context of the US, but arrested mobility happens around the world. My call is a global response, not just a local one."