Denver's decision to invest in its climate and economic future by helping residents buy e-bikes is already paying off for the region, new data shows — and the specifics of how those newly bought vehicles are being used has important implications for other U.S. cities who might follow the Colorado capital's lead.

According to a new joint report from the city of Denver and a coalition of state and national organizations, a whopping 71 percent of the 4,734 Denverites who received an e-bike subsidy last year reported that their new rides helped them reduce the amount they drove, replacing an average of 3.4 gas-powered vehicle trips every single week.

According to surveys, nearly one-third (29 percent) of those riders were completely new to biking before they joined the program, and 67 percent came from low-income households that qualified for up to $1,700 in vouchers, which was enough to get many of them their bikes for free. (The remainder received between a $400 and $900 discount, depending on whether they bought a cargo bike.)

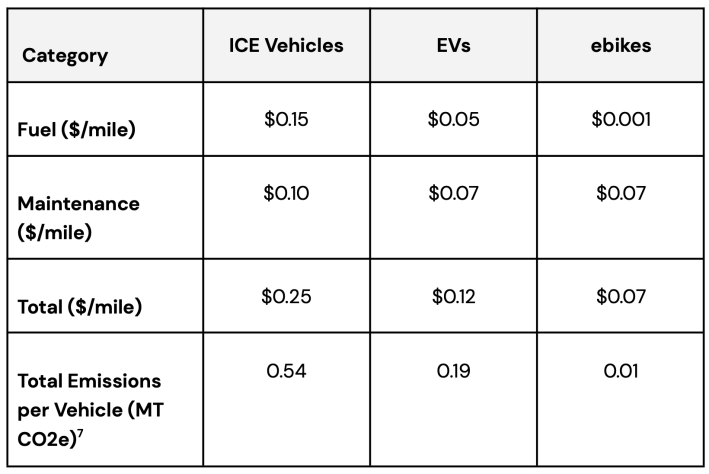

Researchers at the Rocky Mountain Institute estimated that trips taken on all those subsidized bikes last year alone saved participants nearly $1 million in fuel and electricity costs, and saved the region nearly a pound of CO2 emissions per taxpayer dollar spent — a benefit that will continue to grow the longer the bikes are ridden.

That return on investment makes a compelling case that "e-bike subsidies represent one of the best investments a government can make as part of its transportation, climate, and economic strategy," said Ride Report CEO Michael Schwartz.

To help make that case even stronger, Ride Report collected voluntary, anonymized data about how the subsidy recipients actually used their new bikes, using a cell phone app that automatically logged rides anytime it sensed the owner of the phone was in the saddle.

The data set wasn't huge — just 70 people — and probably a little skewed by the modest incentives that the corresponding app sent to users, such as milestone badges for frequent riders and readouts of their weekly and monthly cycling activity to inspire them to keep pedaling. But Schwartz says the findings still provide a rare and important glimpse into how, specifically, free and low-cost e-bikes can change lives — and why they deserve the notice of policymakers who might overlook e-bike vouchers in favor of less cost-effective rebates for electric cars.

"It’s a small sample, but it’s a very deep sample," he added. "There’s this balance you have to strike, between spending a ton of time, resources and money getting the perfect data set, and just accepting that the perfect data set doesn’t exist, but it's still valuable to [collect this information]."

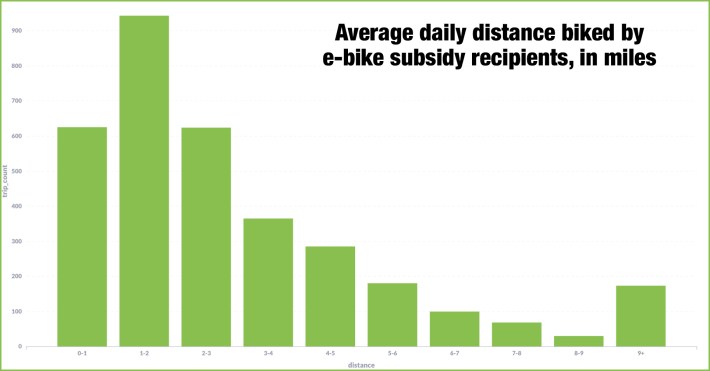

Far from critics' fears that government-subsidized e-bikes would simply "sit dormant in the garage collecting dust," the Ride Report team found that 65 percent of recipients rode their e-bikes at least once a day, and 90 percent rode them at least weekly. Ridership peaked during the morning and evening rush hours, but was spread fairly evenly throughout the week, with slight drop-offs on Saturday and Sundays, and the average trip length was just under 3.3 miles — too long for a comfortable walk, but easily accomplished with pedal assist, and likely tied to neighborhood work commutes and essential household errands.

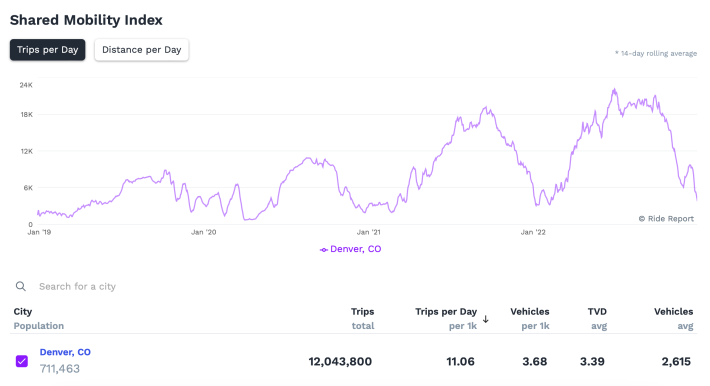

Notably, those trends differ from Denver's shared e-bike fleets, whose data Ride Report also tracks. Bikeshare users in the Mile High City are far more likely to take evening trips averaging just 1.6 miles, which Schwartz says is a clear sign that policymakers shouldn't consider them a replacement for getting residents bikes of their own.

"They're very complementary," he adds. "Owned e-bikes are more about commuting multiple times per week. Shared e-bikes are a way to glue together a car-free or car-light life style, as well as to make those spontaneous trips. We need them both."

Schwartz stresses that Denver's promising new ridership trends aren't an accident, and the city should be commended for designing a program that prioritized mode shift, carbon reduction, and enhanced mobility for underserved groups. City leaders pounded the pavement and partnered with non-profits to make sure low-income residents knew about the program, and nonprofit People For Bikes said they also deserve particular kudos for making vouchers instantly redeemable at the point of sale for a wide range of bikes, including cheaper direct-to-consumer options from online retailers.

If anything, the Colorado capital's approach might have worked too well; Denver official Mike Salisbury said residents "flooded the application site like Taylor Swift fans flooding Ticketmaster," forcing the city to pause the program for months once its its share of a 2.5 percent sales tax had been temporarily exhausted.

Schwartz says the new ridership data makes it clear that Denver's mad e-bike rush wasn't just a flash in the pan, and that daily cycle commutes are quickly becoming critical to thousands of people — despite the fact that the city's bike network is far from perfect. And their success should send a message that other cities shouldn't wait to help their residents buy a ride, as they simultaneously work to make biking safer.

"There’s this chicken-and-egg thing; clearly a good network and infrastructure will drive a lot of people [to ride]," he added. "But e-bike subsidies can be this amazing jump start to a much broader audience of people. ... Even in a city that isn't perfect, you still hear stories about people from whom this program changed their lives in a big way."