The surge of traffic deaths in the first year of the pandemic can't be completely explained by quarantine-emptied roads that made speeding easy — and new data on who, exactly, was involved in those crashes may lead to more questions than answers.

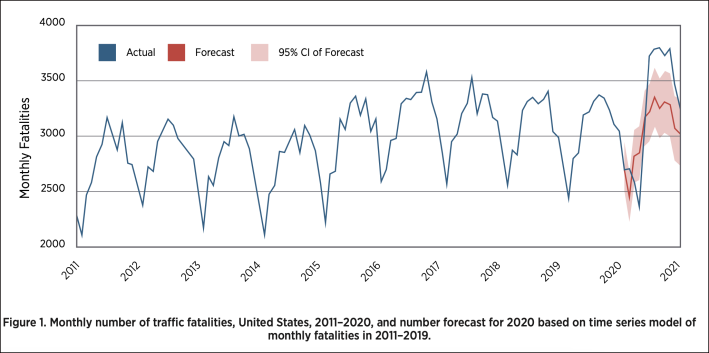

In a bombshell recent analysis from AAA, researchers used advanced statistical models based on pre-pandemic trends to forecast what would have most likely happened on U.S. roads between May and December of 2020 if Covid-19 had never upended American lives. (The ultra-anomalous months of March and April, when road deaths were still low because of strict quarantine orders, were excluded from the analysis.) The analysis, notably, included not just where and when traffic deaths would have occurred, but also who, specifically, would or would not have died.

The "when" was particularly surprising. The study verified that the absence of traffic jams played some role in allowing drivers to reach dangerous speeds on too-wide roads, but the researchers also found that the most significant differences between their forecast and real-world death totals happened in the dead of night, when most roads have always been congestion-free.

Between 10 p.m. and 1:59 a.m., deaths were nearly 22 percent higher than expected; during the typical morning rush hours, by contrast, deaths were actually 6.3 percent lower than the model anticipated they'd be. The late afternoon and evening rush hour, meanwhile, "did not differ significantly from the forecast."

The team behind the study were careful to note that their findings don't dispute the hypothesis that dangerously wide, empty roads played a major role to 2020's crash death toll, which claimed the lives of 38,824 U.S. residents in 2020 and increased 6.8 percent in a single year. As the pandemic drags on, though, they say that we must also closely study the human factors that may be contributing to the crisis — as well as their systemic roots.

“Sometimes, it’s not just a matter of the same problem we had before, but more of it; sometimes, it’s legitimately new problem," said Brian Tefft, senior researcher for AAA Traffic Safety Foundation and the lead author on the study. "Right now, we’re trying to understand why we saw an increase — but to be clear, we don’t ever want to see 36,000 people dying on our roads in the first place.”

Here are four groups of people who were disproportionately involved in fatal car crashes in the early months of the pandemic — though we don't totally understand why yet.

People without valid licenses

It isn't shocking, of course, that people who aren't legally allowed to drive are some of the most dangerous motorists around. What is shocking, though, is how many of them took to the road in 2020 — and how many people died when they did.

The AAA researchers found that a whopping 84.3 percent more drivers with expired licenses were involved in fatal crashes than would have been expected based on pre-pandemic trends, and the number who had never had a license at all were 44.8 percent higher than anticipated. Motorists whose licenses had been suspended or revoked, meanwhile, were over-represented in deadly crashes by 37.5 percent relative to the forecast.

Altogether, the researchers said that "drivers without valid licenses account for almost the entirety of the increase in driver fatal crash involvements" over the study period.

Some of that can be attributed to licensing agencies closing down to stop the spread of Covid-19, but the researchers point out that the vast majority of the unlicensed group (80 percent) were over 20 years old, which suggests they weren't just teens who missed their chance at taking their first road test. (Most states, it should be noted, allow veteran motorists to renew their licenses cheaply online or by mail.) A trip to the DMV, meanwhile, wouldn't have helped make folks with suspended or revoked licenses become road-legal anyway.

“The problem [of drivers without valid licenses] is not new," added Tefft. "What we need to understand beyond that is, why did we see such a large increase in fatal crash involvement among this group in 2020, specifically? We just don’t know, and that, to me, was one of the most concerning findings to me.”

Hit-and-run victims

Previous AAA research has shown that drivers who don't have a valid license are unfortunately likely to leave the scene of a crash to avoid accountability, even if they might not have been found at fault for the collision itself had they stuck around. So it makes a kind of sense that 2020 also saw an increase in hit-and-runs, which clocked in at 31.2 percent higher than originally forecast.

Tefft said, though, that he's not sure that explains why quite so many motorists fled the scene in 2020. He suspects that drunk driving may have also played a role; according to the study, the number of motorists with a confirmed blood alcohol concentration of 0.08 or more were 21.8 percent higher than expected, and that's not counting the ones whose BAC was never accurately measured because they ran away. He also suspects that some were impaired by other substances that are harder to trace, or they simply took advantage of the fact that there were few witnesses because so many of their neighbors were quarantining inside their homes.

“We know from other research that a lot of times when a driver leaves the scene of a crash, it’s later found that they were impaired by substances," he added. "But is that the whole story? We don’t know.”

Dangerous young men

In earlier AAA survey, 4 percent of Americans made the shocking admission that they actually drove more during the earlier months of the pandemic when most people were only leaving their homes for essentials — and that when they did, they participated in a range of deadly roadway behaviors, like speeding, texting, and intentionally running red lights, at rates that far outstripped people who drove less.

That tiny handful of drivers overwhelmingly identified as young men — and the new study suggests that group may have been overwhelmingly responsible for the increase in 2020 road deaths, too.

According to AAA, "about 70 percent of the entire increase in driver fatal crash involvement [between May and December of 2020] was specifically among males under the age of 40." Tefft suspects that increase may have been particularly driven by the minuscule subset of young, male motorists who were emboldened to do risky things on the road when the world shut down, though the data doesn't tell him exactly why.

Vision Zero leaders should probably work on figuring that out — especially because gender discrepancies in dangerous driving long predate the pandemic.

Bicyclists and pedestrians — with an asterisk

Here's the good news: pedestrian deaths actually didn't increase much more than expected between 2019 and 2020.

Here's the bad news: that's in part because experts believe they would have increased a lot whether or not Covid happened — which is exactly what they did.

Walking deaths shot up a horrifying 4.7 percent between 2019 and 2020, which Tefft said was a continuation of "the same horrible trend this has been on since about 2010.” It's additionally horrifying considering that pedestrian activity decreased dramatically in many metropolitan areas during the early months of Covid-19, particularly among people who walk for transportation rather than leisure.

Cycling deaths, meanwhile, increased about 9.3 percent more than expected, which could be explained in part by the famous Covid-era bike boom — but again, Tefft isn't certain.

“We don’t know as much as we need to about what is going in here on a fundamental level," he added. "Is this a person walking or biking for leisure? Is this a person walking 50 feet to their parked car? Is this person going to or from a transit stop? We need to understand what is happening here a lot better we do now.”

As the virus continues to reshape the way we move, Tefft said that it's critical that we take a close look at all the data about death on American roads, and do everything we can to understand the root reasons why so many people are losing their lives — even as those shifts become less dramatic than they were during the global quarantine.

“Is this just a blip, a hopefully a less-than-once-in-a-lifetime event that disrupted the world in a way we’ve ever seen before? Or does this reflect something of a new normal?" he asked. "Although more time has gone by, now, it’s probably still too soon to say whether this is all associated with the pandemic, and whether it will subside when COVID is, hopefully, in the rear-view mirror someday. But based on all indications so far, unfortunately, it isn't looking good. “