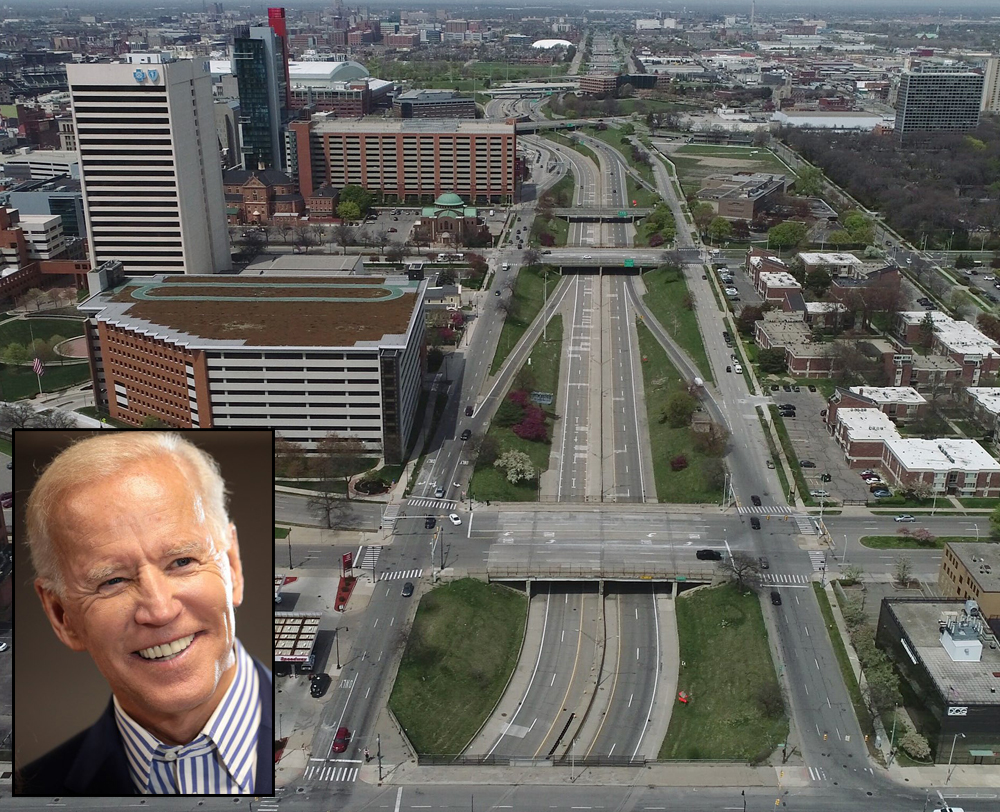

Federal highway grants that typically lavish billions of dollars to build or widen freeways will now be spent to dismantle a Detroit expressway that has separated communities for generations.

In an unconventional move, the U.S. Department of Transportation officials recently leveraged the Infrastructure For Rebuilding America program — a discretionary grant initiative typically aimed at improving freight delivery times — to give Michigan $105 million to kickstart the removal of Interstate 375. The mile-long sunken freeway decimated two Black neighborhoods when it was first built six decades ago, and residents have suffered decades worth of lost generational wealth and damaging health outcomes since.

“This stretch of I-375 cuts like a gash through the neighborhood, one of many examples I have seen in communities across the country where a piece of infrastructure has become a barrier,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg told the Associated Press. “With these funds, we’re now partnering with the state and the community to transform it into a road that will connect rather than divide.”

The award will allow the state to begin dismantling the reviled roadway in 2025, two years earlier than initially planned, and replace it with a street-level boulevard by 2028. Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer originally requested $180 million for the project, which is estimated to cost $300 million, but the federal grant is plenty to get started on construction.

Advocates said they have been waiting a long time for the project to move forward.

“We’ve been talking about this whole idea of the mistakes of urban highways and the impact it had,” said Megan Owens, executive director of Transportation Riders United. “We’re excited that this jumped forward and was recognized as something that really needs to be done.”

Detroit's teardown news, though, comes at a moment when the state of Michigan is poised to potentially build more new highways than ever. As part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, state DOTs won over $110 billion in largely unrestricted road-building funds across five years, which some advocates fear will counteract several modest freeways-to-boulevards programs that have recently been signed into law.

Among them is the Reconnecting Communities Initiative, which was cut from $20 billion to $1 billion during negotiations over the BIL last summer, as well as the Neighborhood Access and Equity Grant program which awards communities nearly $4 billion for restoring transportation connections and community wealth destroyed by highways, which was included in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Still, some say a broader culture change is underway. Once Congress passed the $1.2-trillion infrastructure act in November 2021, federal transportation administration officials began pressuring states to prioritize climate-friendly projects and make repairs before building new asphalt arteries.

Advocates say that USDOT's recent grant-making decisions show that they mean business.

“This is not necessarily highway teardown, but it is designed to reconnect commutes divided by infrastructure,” said Steve Davis, assistant vice president of strategy at Smart Growth America.“This was an infrastructure grant, but it’s clear the administration is taking this idea seriously.”

Now that Detroit's funding has been approved, community leaders want a say in the plan before the state proceeds any further. Transportation advocates want to ensure that stoplights, pedestrian crossings, and protected bike lanes are added to the boulevard that eventually replaces the highway. Some question how wide the new road needs to be, with one iteration showing six and four lanes and another as many as 10.

“Detroit has a moat of highways surrounding it with massive interstates that really blocked off growth, or at least vibrant dense development in downtown,” Owens said.

The most contentious part of the proposal involves what to do with excess property created by the highway’s removal. Renard Monczunski, a transit justice organizer with Detroit People's Platform, wants those tracts dedicated toward affordable housing for residents in a 30-block area displaced by the highway’s construction in the 1960s.

“Deconstructing the highways is the first step but what are the next steps for redressing racial harms?” Monczunski said. “The fear behind this is there is going to be another opportunity for wealthy white billionaires to gentrify those parcels of land, create luxury apartments that do not fit the needs of majority black Detroit.”

Advocates emphasize that while the grant is a good start toward a future with more equitable land use and climate resiliency, but it's still a drop in the bucket compared to the funding spigot the federal government has opened for new highways. A few miles away from the I-375 deconstruction, Whitmer is leading a $3-billion widening and rebuilding project of two interstates, 95 and 74, that wrap the Motor City. Activists had fought to delay the plan, which is proceeding despite Detroit losing 1.2 million people since 1950.

“If you’re going to spend the money to repair these things it makes very little sense to plow money into literally creating the same problem,” Davis said. “That’s a real risk with this funding. The administration needs to use as many programs as possible to steer the ship in this direction, but ultimately it will be up to the state.”

This article has been updated with additional clarity about the nature of the INFRA program and the highway apportionments in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.