There are more violent terrorist attacks against transit in the U.S. than in any other economically advanced country, a new study finds — but those incidents are more likely to be antisocial and random than criminally or politically motivated, raising thorny questions about what officials should do to save lives.

In a recent analysis from the Mineta Transportation Institute, researchers pored over decades of data about major attacks against buses, trains, and ferries, including incidents that targeted physical infrastructure like stations and vehicles, like bombings, as well as those that targeted transit operators and security personnel, like stabbings, shootings, or hijackings.

Notably, that list excluded most instances of violence deliberately aimed at individual transit passengers, such as muggings on train platforms; it also did not include data on attacks committed by drivers against non-transit targets, like groups of protesters, though the institute is studying that horrifying phenomenon, too.

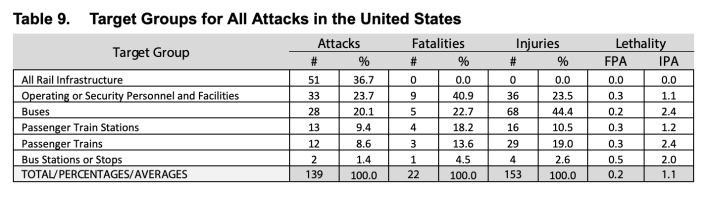

Though it wasn't always the most dangerous country on the list, the researchers discovered that between 2016 and 2021, the United States reported 139 attacks on its shared transportation network, 20 of which involved at least one fatality— more than any of its peer countries, and a stunning result for a nation in which many city’s transit networks are notoriously sparse. The United Kingdom reported 64 attacks over the same period, and Germany had 50 — though none of these results are nowhere near as dramatic as the scale of non-terrorist transportation violence like car-crashes, which claimed 43,000 lives on U.S. roads last year alone.

The details of those violent events, though, may raise more questions than answers about how to stop the bloodshed and win back riders.

In contrast to Hollywood stereotypes, just 5.7 percent of U.S. attacks over the past five years were politically motivated, with right-wing groups responsible for slightly more acts of violence (three) than self-proclaimed jihadists (two). And while 46 percent of the incidents were classed as significant "criminal" attacks, such as headline-making armed robberies, an increasing percentage were seemingly random. A staggering 35 percent of the events recorded by the database were attributed to individuals who had a "history of mental illness" and no clear motive; a further 12.5 percent of assailants were unknown.

"What transportation agencies seem to be worried about, mostly, is terrorist bombing," said Brian Michael Jenkins, who co-authored the report. "But only a handful of [these attacks] had any nexus to ideology or political cause at all. And they weren’t necessarily falling into the violent crime category, either; these seem to be a kind of random anti-social aggression."

Jenkins acknowledges that the study doesn't capture the totality of transportation violence in the United States — nor does it give a clear picture of why, exactly, "anti-social aggression" is on the rise.

The database, for instance, does include vehicle-ramming attacks with what security experts consider to be clear terrorist ties, like an infamous 2017 incident in which a pick-up truck driver killed eight people on a Manhattan bike path before striking a school bus, but would exclude, for instance, a collision involving an individual road-raging motorist who got impatient in traffic and rear-ended the same vehicle. And that's to say nothing of the countless traffic violence deaths that have no obvious, self-declared aggressor, but stem instead from the deliberate inaction of policymakers who perpetuate violent conditions that guarantee tens of thousands of people will die every year — even when drivers don't intend to kill anyone.

Shared transportation vehicles, by contrast, are rarely involved in roadway violence. And that helps explain why, when violent attacks happen on buses and trains, they're often transformed into sensational news stories — even as tens of thousands of car crashes every year are reduced to little more than a few, victim-blaming lines in the paper that were often regurgitated directly from a problematic police report.

"I suspect we’re able to see this [trend of antisocial violence] talked about more in public transit environments simply because these are defined spaces where strangers come together – often very close together," Jenkins added. "But I also suspect [antisocial violence] is about a broader problem in society, even though we don’t have a quantitative analysis of why."

Look at these prison gates that @STLMetro is spending $52,000,000 on. pic.twitter.com/QZM6tKbv2D

— Denis Beganovic (@Beganovic2022) June 17, 2022

Partly in response to negative media coverage, transit agencies in Los Angeles, New York City, and beyond are spending millions in efforts to prevent violent crime on their networks because, they say, riders have been scared off because they fear being physically attacked while riding.

Jenkins and his co-authors say, though, that the specific security tactics those agencies are using to combat violence may not be effective against the kind of antisocial behavior that systems are increasingly experiencing. They point out that traditional "see something, say something" public service campaigns, for instance, are identifying fewer attacks on buses and trains, because transit violence's "increasingly individual and spontaneous nature... makes such attacks less predictable and harder to detect."

Some advocates might add that even the attempt to detect spontaneous violence can carry dangers of its own. As a 2021 Transit Center report showed, people of color and unhoused riders face assault not just from other passengers, but from transit police themselves; transit officials in cities like St. Louis, meanwhile, are facing criticism for spending tens of millions on surveillance equipment and security gates to "harden" stations in an effort to win back riders they say are scared of violent crime, rather than simply using that money to improve the region’s notoriously inadequate service.

Critics of traditional security approaches believe that investing in great service instead of cops and cameras might win back even the most crime-cautious riders — which will, in turn, make transit safer because there will be lots of riders around to discourage violent crimes of opportunity at what would otherwise be near-empty stops. Jenkins says there may be merit to that theory, particularly in the years since COVID-19 slashed transit ridership to historic lows— but agencies will likely still need to do more.

“Some people have blamed [the rise in violent crime] on the pandemic, and I think that’s a contributing factor — but the trends precede the pandemic,” Jenkins said. “People are saying it’s increased stress in modern society, but countries besides the U.S. experience stress, too. … To be honest, we have lots of hypotheses, but we do not yet have the solid data that we are looking for that would be able to analyze each one of these incidents in greater detail in order to reach some broader explanations of cause. … We’ve spent a couple of decades looking for ways to stop one [kind of violence], when in some cases, what’s really discouraging ridership is something else completely.”