A new documentary aims to tell the dramatic story of America's escalating pedestrian and cyclist death crisis — and hopefully, inspire non-advocates to get involved in the movement to end the epidemic.

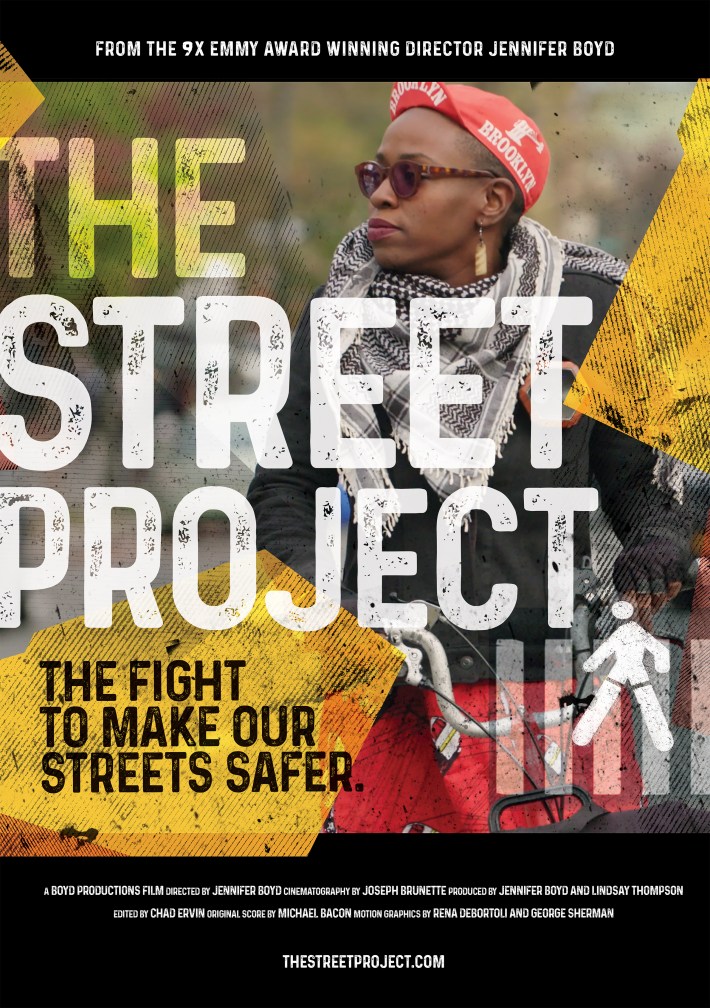

On August 25, Amazon Prime, PBS International, and other streaming services will host the online debut of The Street Project, a new mid-length film that explores the history of how the automobile transformed U.S. streets and the citizen-led fight to give public spaces back to people and save vulnerable road users' lives.

It's the follow-up to filmmaker Jennifer Boyd's 2018 documentary 3 Seconds Behind the Wheel, which offered a deep dive into how the changing nature of motorist distraction is driving national traffic fatality trends. Boyd wondered whether distracted people outside cars were making streets more dangerous, too — though she quickly found that the reality was far more complicated.

"Within a few minutes of starting to do my research, I realized that cycling and pedestrian fatalities have absolutely nothing to do with pedestrian and cyclist distraction," said Boyd, who wrote, directed and edited the film. "I realized we had to look at all sorts of factors behind our fatality rate; we needed to look at street design, at speed, at the shape and design of vehicles, at pedestrian-blaming and the language we use to describe crashes ... It became this really fascinating, rich, in-depth story."

That story will certainly be familiar to street safety advocates, even if it's not to the public at large.

Much of the mainstream media about vulnerable road users deaths that the average American consumes comes in the form of shoddy journalism that transforms preventable car crashes into unavoidable "accidents" and erases their systemic causes. Better-researched articles, meanwhile, too often default to mind-numbing statistics and urban planning jargon that obscure the true human costs of traffic violence, while excellent books that help readers feel the full horror of the crisis and unpack the policy changes that could end it often end up shelved in the minuscule urban planning section at the back of the library.

Boyd says her challenge was not just to explain to a broad audience why 8,327 people lost their lives walking and rolling 2021 alone and how they might have been saved, but to make that story feel emotionally urgent — while still acknowledging that there's good reason to be hopeful.

"The last thing I wanted to do was create another piece of media content that makes people want to bury their heads in the sand and say, 'No more; I don’t want to hear another bad thing about the world in which we live,'" she added.

To do that, Boyd leaned on the power of narrative in a way rarely seen in wonky transportation circles. The film is crafted around the stories of real people like Dulcie Canton, who became a safe streets activist after both her and her mother were struck by hit-and-run drivers in their Brooklyn neighborhood. Advocate Stacey Champion also gives Boyd a memorable tour of her hometown of Phoenix, Ariz., where she’s been pushing for action on walking deaths for years. (Spoiler: Boyd’s cameraman is almost run over in a crosswalk in the process.)

In between, the film is deliberately structured around short, engaging clips that offer an ultra-accessible crash course into concepts like “exclusionary zoning” and the birth of the term “jaywalking” that Boyd hopes advocates can pull out of the larger film and use to educate their communities. She’s also raising money to help advocacy organizations offer screenings of the full documentary that they can use for their own fundraising purposes.

"I really hope the film crossed over and gets people interested in the topic," said Boyd. "Transportation is something that touches every aspect of our lives, even though we may not think about it on a daily basis....so many people walk on our streets but simply don’t think about why they are the way they are."

Boyd, who says she’s become a daily Streetsblog reader during her research for The Street Project, acknowledges that America’s traffic violence crisis is far too vast of a topic to pack into a 52-minute run time.

The film, for instance, only glances on the unique road safety problems of rural communities where car crash deaths disproportionately happen. The complex conversation about what true mobility justice might look like for pedestrians and cyclists of color, meanwhile, is addressed using a few familiar stats about those groups’ drastic overrepresentation in traffic fatality totals and the preponderance of dangerous roads in their neighborhoods. The experts Boyd interviews — authors Mikael Coville-Andersen, Peter Norton, and Jeff Speck — are all well-respected icons in the movement to end car dependence, but they are also all white men, and some advocates may feel the film would have benefited from a wider range of perspectives.

Boyd hopes, though, that The Street Project will spark a far wider conversation than the content covered by her film alone, at a global moment when it’s become more clear than ever that radical change is within reach.

“If there’s anything that COVID taught us, it’s that we can change streets overnight to create safer communities,” she added. “It is possible; we just have to understand that these are our public spaces, and we do have a right to feel safe walking, biking, and using any form of transportation.”