Safety advocates are demanding action following an Amtrak derailment at a "passive" crossing that could have been prevented if policymakers had funded the basic infrastructure and policy changes that safety hawks have been recommending for decades.

At a press conference on Wednesday following a crash between a passenger train and a dump truck in rural Mendon, Mo. that killed four people including the driver and injured as many as 150 more, National Transportation Safety Board Chair Jennifer Homendy slammed transportation leaders for failing to upgrade the unprotected intersection in accordance with 24-year-old agency recommendations.

Like roughly half of railroad-to-road intersections in the United States, the site of the collision was a so-called "passive" crossing that featured no more than a sign on a pole to prevent drivers from entering the track, and not even warning lights to advise them a train was approaching — two particularly deadly omissions in light of the steep grade of the road, which larger vehicles often struggle to climb.

"That recommendation is still as important today as it was in 1998," Homendy said. "Lives could be saved.”

There are thousand soft these crossing all over this country. As a CDL driver, we’re trained to slow down and open our windows and listen for a train, but sometimes the crossings are too steep and trucks get hung. This is a design and money problem in so many ways.

— Wayne Surber (@roadwayne) June 29, 2022

The four people who died were just the latest. Just one day before, a similar crash in rural Brentwood, Calif. killed three out of five occupants of a passenger vehicle and severely injured the other two, adding to a railway crossing crash death toll that's claimed an average of 247 lives every year for the last decade.

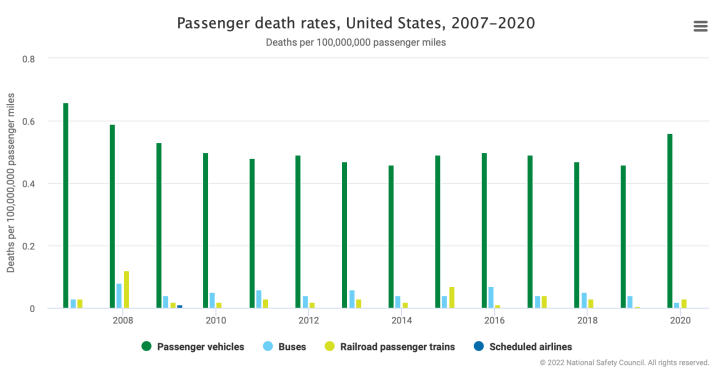

It bears repeating, of course, that even those unacceptable numbers still pale in comparison to the 42,915 people who died in all U.S. motor vehicle crashes last year, and that Amtrak solidly remains one of the safest travel modes. Advocates emphasize, though, that achieving Vision Zero on America's tracks is eminently possible — and legislators' failure to accomplish it is causing needless tragedy.

"I don’t think we should accept any of these crashes as part of the cost of doing business," said Geralyn Ritter, who narrowly survived an Amtrak derailment in 2015 and authored the memoir Bone by Bone about her experience. "There hasn’t been a major commercial airline crash in 13 years, yet every single year, there’s a train derailment. ... I think we’re just unwilling to put necessary funds into saving passenger’s lives."

Ritter acknowledges that the logistics and expense required to install railway safety technology can make changes politically challenging — even if that's no excuse not to do them. Her own crash occurred, in part, because the railway had failed to install a comprehensive "positive train control" system, seeking years of extensions even after a 2008 Congressional mandate to implement the suite of crash-prevention technologies.

If PTC had been in place, she says, it would have prevented the operator of the car from taking a particularly steep S-curve at more than twice the legal speed limit, forcing the train off the tracks. Eight people died, some of whom Ritter suspects would have survived had the rail car also been outfitted with seatbelts and other safety features.

Ritter herself survived, but required 31 surgeries and years of ongoing recovery from pain, depression, and trauma — all of which would have been avoidable if policymakers and railways had taken more safety precautions in the relatively predictable environments through which rails run.

"We know where our trains are, where the tracks are, where the crossings are, where the steep curves are," she said. "The technology already exists to save lives. To me, this is a matter of policitcal will."

It makes almost too much sense that @MoDOT ’s negligence is responsible for this. They were too busy funding highway expansions and lane additions.

— Mitchell Jorstad (@OfficialMitchll) June 30, 2022

Car culture kills.https://t.co/LV9RAv6N5c

When it comes to the sheer scale of America's passive crossing problem, though, mustering that political will won't come cheap or easy.

On the level of simple logistics, fixing a passive crossing often requires a complicated process between the railways, who are usually responsible for the maintenance of tracks themselves, and the state highway authorities who maintain the crossing infrastructure that surrounds rail-to-road intersections. In a February report, the Missouri DOT acknowledged years of urgent resident complaints about the dangerous Mendon intersection and estimated that it would cost $400,000 to fix it, but did not specify a timeline for when those changes might actually be made — nor did it lay out a comprehensive plan to fix the roughly 3,500 other passive crossings within the state's borders, either.

Passive crossings, in particular, are notoriously expensive to fix because they often involve not just adding a gate and a warning light, but running electricity out to a remote rural location, and sometimes even paving, grading out, or otherwise re-engineering the road itself. And that usually doesn't include the costs of more effective and expensive infrastructure, like multiple gates to deter motorists from simply driving around a single retractable arm, sensors that sends signals to approaching trains when a car is coming, or ideally, building a bridge over or under the track itself.

The most recent estimate that Streetsblog could find for how much it would cost to correct every passive railway crossing in the United States was $14 billion. That number, though was from 2005 — and the largest federal safety program specifically earmarked for passive crossings pays out just $245 million a year.

That leaves state and regional DOTs to fill in the gap — the same agencies that are notorious for building new highways rather than making the ones they've already got less deadly.

‘We heard a massive bang and I knew the train hit something’ — These passengers gave a firsthand account of the Missouri Amtrak crash pic.twitter.com/95iyYHihgA

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) June 28, 2022

For Ritter, the Mendon crash is an urgent reminder that stopping preventable railway crashes is so crucial precisely because the mode is already so much safer than driving.

"I don’t think people should be scared to ride the train; the rational side of me knows the statistics, that it's safe," she said. "But I also don’t think we can accept that train crashes will just happen. I don’t think 'pretty good' is good enough when the technology exists to save lives ... I still ride the train, but I still feel in my bones sometimes. When the train goes by a sharp curve, I bow my head and say a little prayer for the eight people that died."