A handful of cities across America are building out bike lane networks faster than ever — and the secret ingredient isn't concrete and paint, but strong partnerships and even stronger public messaging, a new analysis argues.

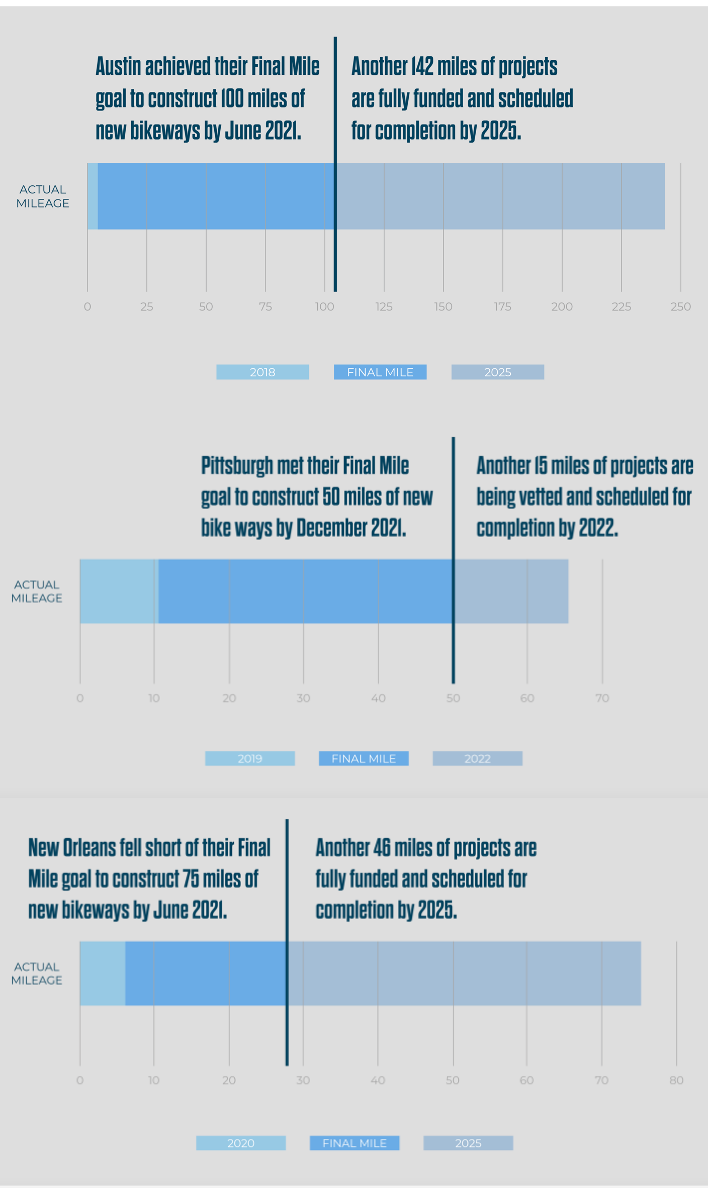

Last week, nonprofit People for Bikes announced the results of its groundbreaking "Final Mile" program, which sought to radically accelerate the construction of cycling infrastructure in five U.S. cities in just two years, with a focus specifically on low-stress, separated lanes. The communities in the pilot — Austin, Denver, New Orleans, Pittsburgh and Providence, R.I. — each received an average of $2.2 million to help them achieve an aggressive, community-specific goal to rapidly multiply their bike lane mileage, in addition to administrative support.

For some communities, like Austin and Denver, those goals required local leaders to build as much as 100 miles of new high-quality lanes in 24 months or less — a Herculean feat for cities that had little infrastructure before.

Unlike most sustainable transportation accelerator programs, though, not a dollar of the Final Mile money went to construction material. Instead, PFB focused most of its money on the coalition-building and marketing needs that cities struggled to prioritize before they broke ground — needs which experts say can ultimately make or break projects like these.

"When you build a bike lane network, everybody is looking for resources, and often, the budget for marketing gets diverted," said Kyle Wagenschutz, who lead the project and today has adapted its lessons as a partner at nonprofit CityThread. "[Cities] end up saying, 'Should we really spend this money on communications if we can’t pay the engineers?' Because at the end of the day, we have to pay the engineers. ... With Final Mile, we said, 'Let’s make sure everyone has their basic needs met, and then let’s go big and build a whole network at once.'"

The strategy worked. Four out of five of the cities met their mileage goals, while the only one that didn't, New Orleans, completed the highest percentage of fully protected lanes in the pilot, despite being hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic during the accelerator period.

Secret ingredient #1: Getting staff, electeds and community leaders to the table

To accomplish those impressive results, People for Bikes brought together three key groups who often struggle to align their efforts around active transportation: the city officials who carry out bike lane projects, the elected officials who support them, and the community organizations who engage the residents the lanes will impact most. Because if all three don't come to the table, Wagenschutz says, even the least ambitious initiatives often founder.

"It’s almost like a stool — it can't really stand without all three," he added. "Two legs of the stool can sometimes work together to get programs across the finish line, but it’s going to be a slog without the third."

Even when communities do manage to get all stakeholders to collaborate, though, that doesn't mean all three will find the resources they need to accomplish aggressive goals.

"If your city’s going to build bike networks quickly, do they have enough people design in a short period of time?" Wagenschutz said. "Do nonprofit partners have enough money to do that meaningful on-the-ground outreach? Are elected officials aware that there are more supporters for this work than there are people opposed, so they can feel confident actively supporting this project, too?"

Secret ingredient #2: Getting the messaging right

Wagenschutz is careful to note that public support for bike infrastructure can be a bit of a moving target as big projects get underway, even though residents of Final Mile cities overwhelmingly expressed enthusiasm for adding more protected cycling facilities at the start.

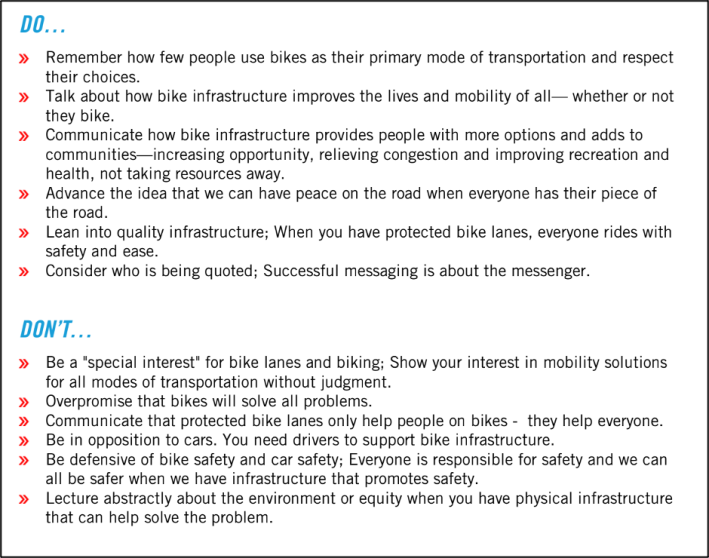

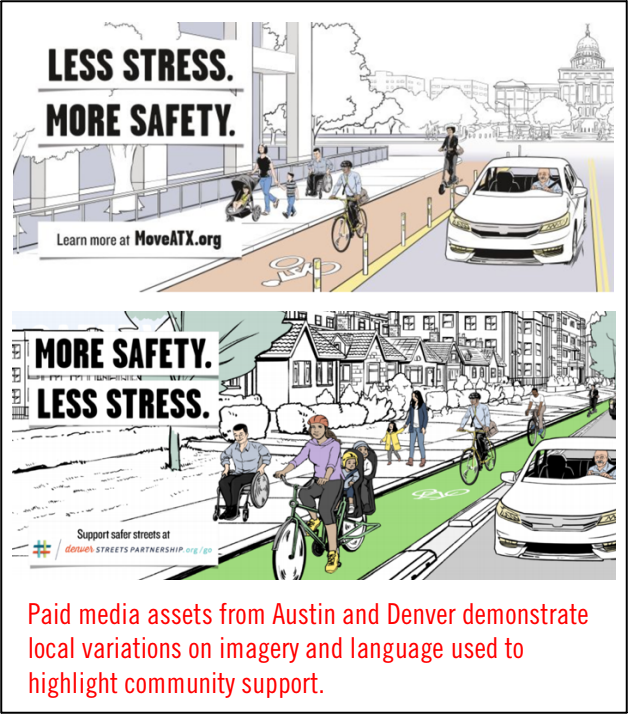

That's why, in addition to supporting and uniting community institutions, People for Bikes added a second secret ingredient to the mix: city-specific research into the kind of messaging that could bring doubters into the fold, and keep ambitious build-outs on track.

"In every single city that we’ve worked with, we've found that there is overwhelming community support for building bicycle networks, even if it doesn’t feel like it," Wagenschutz added. "But when you say to residents, 'You can have [bike lanes], but it requires a trade off —in terms of parking, or traffic speeds, or whatever it is — then that support softens. Communities are doing a really bad job of selling the value of this work to the people for whom those tradeoffs don't seem immediately worth it: people who drive cars every day, and who we expect to never get out of their cars."

Of course, not all messaging will work equally well in all communities. That's why PFB sponsored a series of focus groups in the Final Mile cities, as well as five others, to get a sense of what language might move the needle in each unique place, and particularly among its underserved Black and brown communities.

In all 10, though, a few common themes emerged.

"One big takeaway is, don’t lead with the bike," said Jose Maldonado, vice president of Marketing and Communications for the organization. "We’re not trying to create an anti-car program; this is really about mobility for all."

Secret ingredient #3: Act now — don't wait for policy to catch up

Both Maldonado and Wagenschutz acknowledge that in a perfect world, cities wouldn't have to finesse their messaging about cycling projects so much, or work so hard to build inter-institutional support for this essential infrastructure.

And both emphasize that someday, policy should require communities to complete their streets by default, rather than relying on millions in philanthropic dollars to help them fill the gaps.

"I often say, it only takes one angry person to disrupt a well thought-out, well-designed bike project, but even thousands of people protesting a highway project can’t always stop it," added Wagenschutz. "That’s the imbalance that the Final Mile was designed to help correct. ... The majority of people living in cities want to see this infrastructure happen, but when it does happen, we don’t get the results we want: we get disconnected networks that don’t get people where they need to go. And in the meantime, the highway machine continues unimpeded."

For now, though, Wagenschutz thinks that the Final Mile Project offers a blueprint for philanthropic interests to supercharge local bike lane building efforts that can take cities decades on their own. But even for communities that don't have an angel investor waiting in the wings — or don't get selected for People for Bikes' next round of funding, which Maldonado says they're exploring now — that blueprint still offers indispensable lessons.

"The Final Mile project is saying, basically, that we can do something today that’s radical," he added."We can build 100 miles of bike lanes in 24 months. And we can build momentum for long term policies that make it easier for this to happen everywhere."