Automakers are finally testing an automatic anti-speeding technology on its vehicles that could save countless lives on roads around the world — but only if drivers don't turn it off first.

On May 24, Ford Europe announced the it had begun trials on a new technology that will automatically force drivers to obey local speed limits thanks to an invisible virtual boundary (aka a "geofence") that signals to the car that the rules of the road have changed. City officials could also, theoretically, dynamically adjust those rules when roadway conditions are too hazardous to travel at the posted limit, like during winter storms, when road workers are present on the side of a highway, or at times of day when students are likely to travel through a school zone on foot.

Invented way back in the mid-1990s, geofencing technology is already in use by some micromobility companies to automatically throttle scooter and e-bike speedometers — or even disable vehicles altogether — when they enter places that typically have a lot of walkers, like pedestrian plazas and college campuses. Automakers, though, have yet to embrace the technology, and U.S. regulators have been slow to require it, even after Europe announced that it would mandate "Intelligent Speed Assistance" on all new vehicles by July 2022.

“Connected vehicle technology has the proven potential to help make everyday driving easier and safer to benefit everyone, not just the person behind the wheel,” said Michael Huynh, manager of city engagement for the German division of Ford Europe. “Geofencing can ensure speeds are reduced where — and even when — necessary to help improve safety and create a more pleasant environment.”

Daily I am really frustrated cars don’t have speed governors. People drive way too fucking fast. There’s no need to go above 20 mph unless you’re on the interstate or a freeway.

— Courtney craves chill cycling (@FullLaneFemme) May 31, 2022

The trouble with Ford's "smart" tech, though, is that drivers can easily outsmart it — and that's by the company's and regulators' own design.

Much like micromobility vehicles, cars equipped with Geofencing Speed Limit Control will automatically slow down the moment their drivers turn onto a calm neighborhood street. Unlike scooter-riders, though, those same drivers "can override the system and deactivate the speed limit control at any time," as Ford noted in the release.

Ford reps also bragged that the tech "could help drivers avoid inadvertently incurring speeding fines and improve roadside appearances," but did not discuss the potential downsides for other road users when motorists decide they'd rather risk a ticket than do their part for public safety. The company also did not mention whether it would study which factors might compel a driver to turn the critical new safety feature on or off, so policymakers could at least prepare themselves in other ways. (Ford reps did not respond to a request for comment)

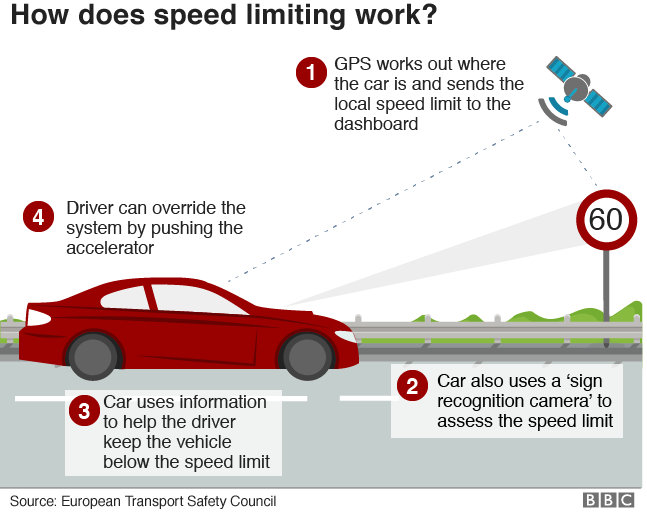

It's important to note, though, that even Ford's imperfect approach to speed-limiting technology is still better than the watered-down version that the European Transport Safety Council will require on all new cars in just a month.

That's because the so-called "mandatory speed governors," at least in the limited form negotiated by the European Union leaders, will not automatically govern a vehicle's speed. Instead, they'll issue a simple audible alarm that drivers are going too fast for local conditions, which will cease after no more than five seconds unless drivers shut it down. The EU argued that motorists need to be able to disable their Intelligent Speed Assist "for safety reasons," such as when they're passing another motorist, attempting to transport a passenger to a hospital, or being chased — three scenarios that represent a tiny fraction of the time drivers actually spend on the road.

And again, with the Ford tech, drivers will be able to disable Intelligent Speed Assist whenever they find it annoying, which Council research shows they probably will.

That temptation would likely be even stronger on U.S. roads, where many legal speed limits are set high enough to all but guarantee death or serious injury to people outside vehicles, and roads themselves are designed to tacitly encourage motorists to travel even faster.

Or, as Treehugger's Lloyd Alter once memorably put it: "imagine being forced to go 25 miles per hour on an empty road engineered for people going twice as fast, in vehicles engineered to go four times as fast."

Of course, it's perfectly possible to imagine a world where U.S. automakers are one day required to install dynamic, state-of-the-art speed limiting technology that will prevent motorists from achieving deadly velocities anywhere they might take another road users' life.

But until that technology is 1) impossible to override except in the case of a true emergency, 2) backed by local speed limits low enough to actually save lives, and 3) reinforced by road designs that slow down every driver on the road, whether or not they have the latest automated vehicle tech on board, we probably shouldn't count on it too hard to end America's traffic violence crisis.