Editor's note: A version of this article originally appeared on Strong Towns and is republished with permission. Amy Stelly was also interviewed by Streetsblog for a recent article about the Freeway Fighters Network, of which she is a member; find out more here.

As an artist, I love living in Treme — a historic Black neighborhood in New Orleans — especially when it’s quiet. It’s nicest when the humid air covers you like a warm blanket, and the only things that pierce it are sounds of birds, insects, or my new neighbor’s trumpet. He’s a master, but you never know when he’s going to practice, so you have to listen. I first heard him at night, when the music was romantic and sultry. And then, I heard him again during lunch. His études were a treat.

I don’t want to lose those moments, especially in an ever-changing community that has a different sensitivity to noise, sound, and culture. So, it’s imperative to fight for Treme, which means creating environments that improve our quality of life so we can live longer and become even better, more prolific artists. But to many Black people, that fight for improvement more often than not translates into displacement — and the fears are real.

For example, my neighbor bought her house for $70,000 eight years ago. It’s now going on the market for $430,000, and she expects to get offers that are over asking. Most of the folks who have lived in the neighborhood and give Treme its flavor can’t afford to buy that house, nor could they afford to rent it. The neighborhood is flooded with properties like that, so, the indigenous folks have to move. They can’t afford to live here anymore. The burden of housing costs has become too big, and, to many, my efforts to tear down I-10 (the elevated Claiborne Expressway) also don’t help. It scares them.

Unfortunately, the truth is that Treme and the 7th Ward, like many neighborhoods across the country, are saddled with an aging, unsafe, polluting piece of highway infrastructure. We have to do something about it. I learned about the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) more than two years ago, and at that time, I urged Mayor Cantrell to begin having community conversations about equity and displacement — two areas where urbanists have failed in the highways-to-boulevards movement. She didn’t heed my advice. So, as a community, we must initiate the conversation and develop strategies to remain in place on our own.

Moreover, this is the time for New Orleans to seize the opportunity to move forward, since there’s money allocated to remove highways in the IIJA. One of my colleagues, David Waggoner of Waggoner and Ball Architects, identified the removal of the Claiborne Expressway as a hero project. I agree. More and more heroes are saying “yes” to its removal, and I hope the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (LaDOTD) will come to adopt the same mindset.

Quite recently, the LaDOTD’s secretary, Shawn Wilson, invited me to make the case for removal during his technical tour for members of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). I was invited to speak because I am a resident of Treme, and an architectural and urban designer. I have been a long-standing proponent for removal of I-10 over Claiborne.

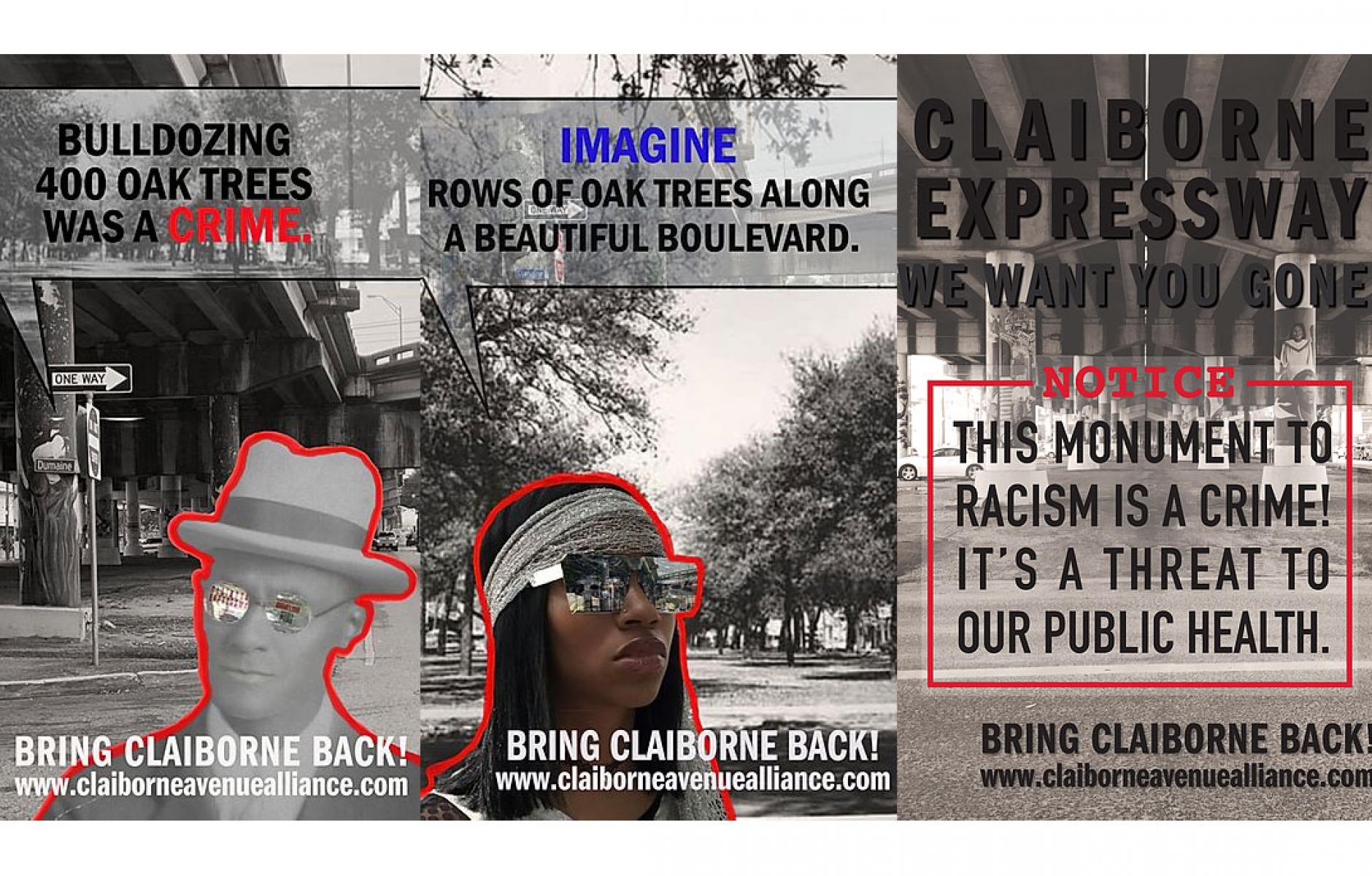

The good news is that I am not alone. Members of the Claiborne Avenue Alliance, a grassroots coalition that came together to protest the City’s plan to develop a container village under the interstate, along with a wide array of other community members, also believe that New Orleans would be better off if the Claiborne Expressway were removed.

You may be wondering: How did I get on the LaDOTD’s radar and earn the chance to address their fellow transportation officials and engineering experts?

The answer: My tactical urbanism campaign to remove the highway captured media attention. Not to mention, I’m pretty sure their eyebrows were raised after President Biden identified the highway as an example of transportation investment that caused historic inequity in need of redress. During interviews about the Claiborne Expressway, I took things a step further by openly challenging our state officials to move near an urban highway and subject themselves to the quality of life we’re forced to endure every day. I’m fairly sure Louisiana’s state officials took note.

I consider Secretary Wilson’s invitation a blessing. He gave me a huge opportunity to influence highway builders, and I am thankful for that. What made the opportunity even more interesting was that Secretary Wilson invited Ujamaa Economic Development Corporation, the nonprofit that hopes to develop under the interstate, to present their case, too. Ujaama, a product of former Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s administration and my self-declared opponent, believes that the highway can be repaired and should remain. Unfortunately, they don’t understand what that entails, or what that would mean for Treme.

The Claiborne Expressway doesn’t meet current safety standards. It doesn’t have a left shoulder, which endangers the lives of stranded motorists and traumatized crash victims. Drivers have to tend to their wrecked cars and each other in the fast-moving, left travel lane. There’s no way to escape conflict with an inattentive driver, and pushing a disabled car to safety means crossing two lanes of traffic moving at more than 40 miles per hour.

At the same time, expanding the highway to meet the standards would sound the death knell for the neighborhood. The right-of-way for the expressway is constrained, and the expansion of even a few feet would require the acquisition of large swaths of land. That would kill Treme. I would lose my house, Ujaama would lose its office, and their followers would lose their businesses and homes, too.

During the Claiborne stop for the AASHTO tour, my opponents distributed flashy handouts and showed huge, glossy posters with aspirational renderings illustrating events and gatherings under the elevated highway. I had an iPad, a PDF, and one bite at the apple to change the hearts and minds of people who expand highways for a living.

What made the work even more challenging was that I was forced to present in a bar. My opponent offered her office space for the tour stop and presentation but reneged the morning of. She told me that the owner of the barroom next door had agreed to help me out. Fortunately, the establishment had a screen, so one of the stakeholders that I invited ran to her business to get a projector. We made it work.

Claiborne has the power to elicit all kinds of emotions. Going in, I knew that my opponent would try to sell her dream with pretty pictures and stories of musicians’ love affairs with the acoustics of “the bridge,'' our colloquial moniker for the highway. Without realizing it, she handily proved the point about noise pollution for me. She presented her posters in the front yard of her office on Claiborne Avenue. The noise from the looming expressway was so loud it was difficult to hear her. One of the engineers questioned the wisdom of moving forward with a plan to build anything under the expressway, given its challenges. Moreover, forcing the members of AASHTO to stand in the heat alongside the dirty, belching monster for nearly a half hour clearly illustrated the perils of having to live and work near an urban highway.

In contrast, I had two indisputable things on my side: science and math — languages that engineers understand. During my presentation, I cited decibel readings which confirmed that we had been exposed to dangerously high levels of noise while listening to my opponent in her front yard. I showed photos of a stranded driver in distress who was in danger of being hit by an oncoming car. I had been lucky enough to capture the incident showing the perilous conditions on the expressway only days before. I paired the images with a chart of AASHTO’s standards that had been published on the Federal Highway Administration’s website. It was clear that the geometry of the highway did not meet the minimum dimensional requirements codified in the standards.

I am a big fan of the super sleuth. I’ve always dreamed of being one. They break the codes that stand between us and mysteries that are seemingly impossible to understand. Cracking both technical and social codes means knowing that they have their own parlance. Therefore, campaigning to remove a highway requires you to understand all of the pertinent processes and codes — you need to acquire a whole new vocabulary.

My strategy of speaking to engineers by using their own parlance and code as a justification for removal apparently paid off, because I received feedback about my presentation from a colleague at our transit authority the next day. He hadn’t been at my presentation, nor was anyone from his agency. My name didn’t appear in their agenda, either, so very few people knew that I had been given the opportunity to state my case. Yet, he knew I had pitched to AASHTO for the removal of Claiborne. I had moved someone in the room to spread the word about my pitch for removal—in other words, my strategy worked. I cracked the code!

It’s imperative to look forward to tailoring the redevelopment long before the highway is removed. The Claiborne Avenue Alliance has started to organize the community to create an equitable, citizen-driven plan for Claiborne. We started by holding a community meeting on the anniversary of the rollout of the infrastructure bill that highlighted the Claiborne Expressway.

We used the meeting as an opportunity to begin educating the community about current conditions and receiving their input. We invited experts to speak about our transportation infrastructure, the state of affordable housing, economic development, and stormwater management. We also invited Congressman Troy Carter and Representative Royce Duplessis to give keynote addresses during the plenary sessions. Most importantly, we encouraged community members to speak openly and honestly about their concerns, hopes, and dreams for Claiborne. We listened and invited them to work with us to create a plan, with the goal of presenting it to decision makers that will provide a strong counterpoint to any proposed expansion of the highway.

The Alliance and our fellow advocates from around the state are positioning Claiborne as a cautionary tale for all who are looking for the $1.2 trillion in infrastructure funding to “rain money” down for highway expansions in Louisiana and the rest of the country.

So, what can advocates learn from the Alliance’s campaign about how to crack the code of a byzantine DOTD process?

- Start valuing people over cars, and start valuing equity and resilience.

- Say no to huge, irreversible projects, and start thinking in terms of small, incremental development.

- Stop fearing change. Embrace a process of continuous adaptation.

- Stop building based on abstract theories, and start building places that work. That’s what our neighborhoods need today.

- Carefully guide future growth and implement plans based on sound finances.

I am confident that the work of the Claiborne Alliance will be fruitful and that we will see the removal of the Claiborne Expressway. It’s painful to see pictures of Claiborne’s thick, beautiful canopy of oaks being bulldozed and replaced with a six-lane, elevated, concrete highway. I fear that if we stop talking and working toward equity and removal, other communities like the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans and neighborhoods in Lafayette and Shreveport, Louisiana, will suffer the same, ugly fate.