The same tool that communities have used for decades to make commutes easier on drivers can be refashioned to reduce reliance on automobiles, a leading planning consultancy argues — and there's a better blueprint that cities can follow right now.

In a new report from NelsonNygaard, transportation planners proposed an overhaul of the conventional "transportation demand management" plan to "manage" their communities' dependence on single-occupancy vehicles, rather than simply manage peak traffic flow.

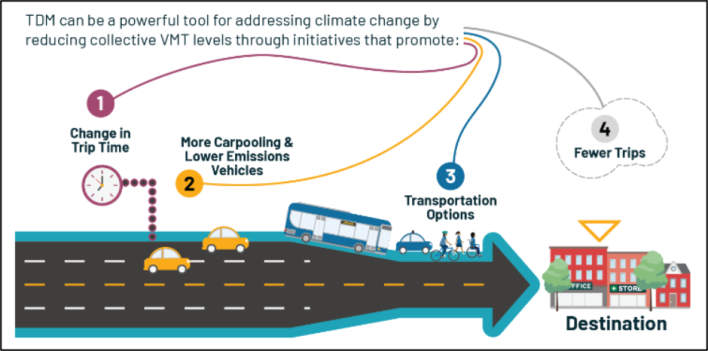

Transportation demand management is sometimes used by cities to accomplish driver-focused goals, like cutting congestion at rush hour, but it's rapidly evolving into an umbrella term that encompasses everything from limited, local strategies, such as workplace bike-to-work challenges, to sweeping and impactful ones, like building great transit systems.

The authors argue, though, that even the most well-intentioned TDM plans don't usually do enough to change how people get around — and that many are tantamount to "tweaking the operations of streets and highways to accommodate ever more cars."

That's particularly true for city residents who aren't looking for an alternative to a busy five o'clock commute, because they're already riding the bus to a night shift job across town, long after white-collar motorists have already made their way home on the highway.

"Especially when focused on providing 'commute options,' such TDM programs primarily benefit those with steady, conventional forms of employment and traditional, workweek schedules," the authors wrote. "While such programs can provide significant benefits that advance equity among participants...their focus on people with the option of a drive-alone, rush-hour commute invariably excludes from its benefits the most consistently disenfranchised, under-served populations within our communities."

To illustrate what a better TDM plan could look like, planners at NelsonNygaard built on work they'd done as part of the Bloomberg Philanthropies American Cities Climate Challenge to compile one, super-charged guidance document that other cities could follow.

That clearinghouse of strategies includes:

- Eliminating mandatory parking minimums and implementing car parking maximums.

- Requiring developers to offer parking only as an optional, fee-based amenity.

- Dynamically pricing curb access to encourage the use of other modes, and monitoring it closely.

- Charging drivers appropriate tolls to use the roads, particularly at the most-congested times.

- Updating zoning codes to incentivize the construction of housing near transit.

- Requiring developers to use strategies proven to reduce car use, like requiring tenants of new office buildings to offer employees transit benefits.

- Requiring employers over a certain size to use strategies proven to reduce car use, like giving workers subsidized transit passes.

- Reforming the process of conducting "transportation impact analyses" of proposed new developments to shift focus away from vehicle speeds and delay and consider all “person-trips,” not just car trips.

Most of those strategies, of course, are already well-known elements of the sustainable transportation playbook. By codifying them into ambitious TDM plans, though, cities can transform the tedium of drivers' sitting in traffic and the myriad challenges faced by people who use active and shared transportation. And as COVID-19 continues to upend U.S. travel patterns, there may be no better time than now.

"Americans’ dependence on cars and trucks as the dominant means of personal transportation is built on a foundation of dispersed and isolated land use patterns and automobile-centric urban street design," the report concludes. "These decisions are propped up by thousands of subtle and pervasive rules, regulations, processes, and incentives that have accumulated over time in city, state, and federal law. ... Recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic offers further opportunity to shift focus away from 'flattening the peak' to these broader goals more aligned with core values around equity, sustainability, and access."