St. Louis's controversial decision to vote down a resolution that would have banned legislators from voting over Zoom while driving — a measure which one lawmaker debated while actively operating a car — is sparking a heated conversation about distracted driving, and how little America does to stop it.

Last week, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, the city's primary legislative body, voted down a series of resolutions that would have prohibited members of the board from participating in debate, being counted as present, or voting in remote meetings if they did so on a cell phone from behind the wheel of a moving car. Like all cellphone use behind the wheel, Zooming while driving can effect drivers' reaction times as much as being drunk, even if they're doing it hands-free.

Since the Board began holding remote meetings at the start of the pandemic, Alderwoman Anne Scwheitzer of Ward 13, who introduced the resolution, says she's observed colleagues driving on Zoom "at least once a week," and that her constituents were growing alarmed — particularly in light of the region's ongoing traffic violence surge. Car crash deaths in the greater St. Louis area hit a 10-year high in 2020, and registered their second-highest total in 2021; walking deaths alone are 25 percent higher today than they were before the pandemic.

"[This resolution] seemed like a really simple way for Alders to address a small part of this enormous problem," said Schweitzer. "It turned out to be much harder to get passed than I ever anticipated."

At least one alderperson — Brandon Bosley of Ward 3 — participated in the two-and-a-half hour committee debate over the resolution from the driver's seat, and used an abelist slur to defend the practice as normal. [Content warning: a redacted version of that slur appears in the quote below, and in full in the video.]

"I just want to say this; we're not r*tarded. ... People have invented multiple things to drive while being hands free," said Bosley. "I guarantee you Ald. Schweitzer [who introduced the resolution], and every single person on this call has utilized the phone before while it's on speaker phone."

2/23/22, Rules Committee, Brandon Bosley (Alderman Ward 3, @BrandonFBosley ) debating against a resolution banning #DrivingWhileLegislating ....while #DrivingWhileLegislating.

— STL PoliticClips (@StlPoliticClips) February 23, 2022

CW: he does use the r word. pic.twitter.com/oLj0Typq9t

Bosley is right that distracted driving is normalized in much of America, and that the right to do it is enshrined in many state and local laws — though that doesn't mean it should be.

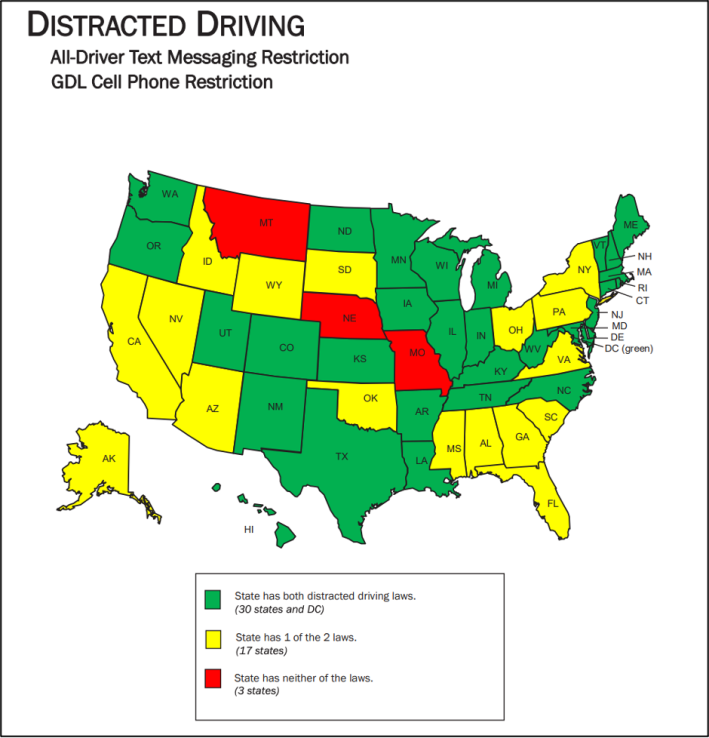

The Show-Me State, which has some of the permissive distracted driving laws in the nation, is one of just two states that allows all motorists — including teens driving under learner's permits — to use both hand-held and hands-free cellphones to place calls, and drivers over 21 are legally permitted to send texts. (The other is Montana.) But more than a dozen other states still allow child drivers to use phones behind the wheel, and many make distracted driving only a secondary offense, meaning that officers have to catch drivers committing other crimes in order to write them a ticket for doing it.

Another permissive state, Ohio, made national news last year when a member of its state legislature was caught Zooming while driving during a government meeting on the same day the legislature was set to consider its own distracted driving bill. Even after an image of the lawmaker wearing a seatbelt against an obviously fake Zoom background of his living room went internationally viral, that bill has failed to pass, and using a cellphone behind the wheel is still a secondary offense in the state.

Street safety advocates say such policies fly in the face of decades of research that show even hands-free devices can reduce a driver's ability to react to visual information on the road by as much as 30 percent — and that drivers stay distracted for an average of 27 seconds even after they issue a voice command to hang up on a call.

There's less data on the specific safety impacts of using new technology like videoconferencing while driving, but since 2013, NHTSA has advised that in-cabin technology shouldn't take a motorist's eyes off the road for more than two seconds at a time, or a total of twelve seconds over the course of a signal task.

Those guidelines haven't been heeded by most makers of on-board "infotainment" systems, which safety hawks say are making increasingly egregious grabs for a driver attention as they become the standard on new cars — which may be part of why people like Alderman Bosley think completing comparably complex tasks, like legislating behind the wheel, are safe and socially acceptable.

Other members of the board, like Alderman Sharon Tyus, compared voting over Zoom to more common driving interruptions like talking to a passenger or having a barking dog in the car, though safety experts disagree that those are comparable to tasks that require a driver to actively take their eyes off the road or engage with a touch screen. (Schweitzer adds that aldermen are often tasked with reading legislation and supplementary materials during committee meetings, which takes much longer than a quick glance at a screen.)

"The biggest difference that we see is that our smart phones are designed to capture and keep our attention," said Kevin Hahn-Petruso, policy manager for Trailnet, a local sustainable transportation advocacy group. "Anyone who's spent time on Zoom, we know that it's far more taxing on our attention that sitting in a car talking to a passenger."

St. Louis advocates are optimistic that the region will ultimately take action to end distracted driving, even if it won't happen amongst the Board of Aldermen first. The Missouri State Senate recently introduced legislation to tighten the state's cell phone laws in recognition of a 30 percent surge in cell phone-related crashes over the last five years — and those are just the ones that drivers admitted to, or that police were able to determine after pulling a driver's phone records via a search warrant after a serious crash.

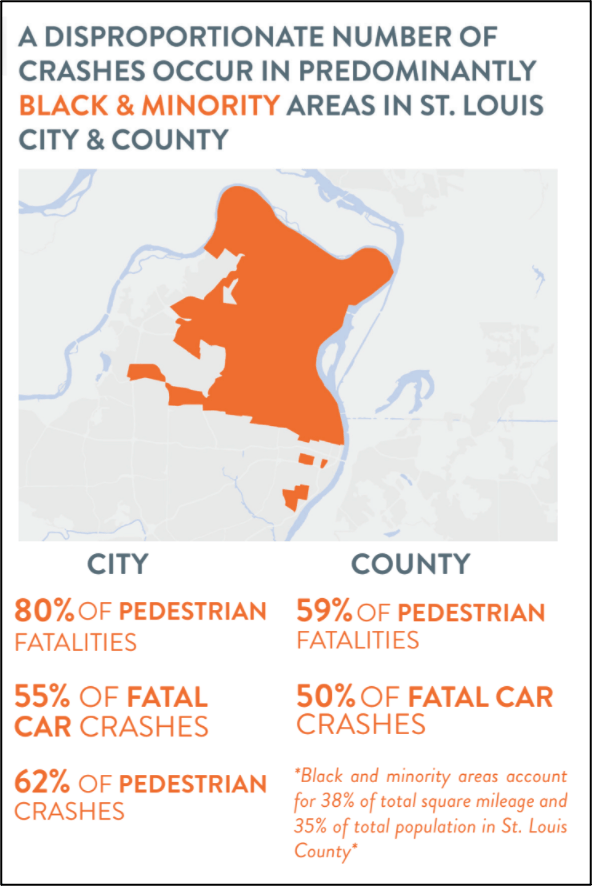

Hahn-Petruso is careful to add, though, that stronger laws alone won't eliminate road deaths — and if not implemented thoughtfully, they could inflict additional harms on the already over-policed communities of color where most St. Louis road deaths happen. That's why his organization advocates for a more holistic approach, including implementing mandatory driver education – Missouri currently has none — and sharing the stories of traffic violence victims, and the loved ones who survive them, to change public attitudes towards dangerous driving.

Most important, he says, St. Louis must redesign its dangerous street network, which runs a disproportionate number of wide, high-speed roads through Black neighborhoods — exactly the kind of designs that lull drivers into a false sense of security that studies show can entice them to pick up their phones and hit the gas.

"All these elements need to happen in concert with each other," he adds.

Fixing those racist transportation choices, though, is largely left up to St. Louis's fragmented ward capital system, which gives alderpeople broad power to approve or deny proposed road redesigns in their neighborhoods.

Aldermen like Bosley and Tyus, who both voted against the distracted driving resolution, control two of the deadliest wards in the city, both of which are majority Black — but despite the racist impact of traffic violence on their constituents, they claimed that prohibiting legislating behind the wheel would have a racist impact on Black alders, many of whom are juggling their responsibilities as lawmakers with other jobs and the demands of raising families. (Joe Vacarro of Ward 23, who is White, agreed with Bosley's assertion that the legislation was "most certainly racist in nature," though he has a track record of being flippant about street safety for other reasons, too; he recently claimed he was targeted for a speeding ticket because he was driving an expensive pick-up truck, not because he was traveling 16 miles over the limit.)

Schweitzer, who is White, says she cares about the challenges her Black colleagues face, but points out that they're not the only ones negotiating the difficulties of legislating remotely in an unprecedented time. The resolution failed, in part, because two White alderwomen, both of whom seemed supportive of the effort, had to leave the Zoom early to pick their kids up at school; both opted not to participate in the upcoming vote while driving.

She says she supports policies to give all these alders a better work-life balance, but making streets more dangerous isn't the way to do it — especially since it's not yet clear whether the city would be held liable if an alder hit someone while legislating behind the wheel.

"The pandemic has exacerbated all kinds of life concerns for everyone, but I don’t think that’s a good enough reason to put other people’s lives in danger," she said. "It is our job to attend these meetings, be fully present, and make the best decisions we can for our constituents. You can't do that in a moving car."