This article originally appeared on Strong Towns and is republished with permission.

Sometimes, a story comes to our attention that, if it were written in a work of fiction, would be rejected by the editor as too on-the-nose. So it is with this juxtaposition of two news stories from the same week in December. Both stories come to us from Pocatello, Idaho, a city of just over 50,000 in the southeastern part of the state. We were tipped off to this by our friend and one of America’s most tireless and incisive road safety advocates, Don Kostelec. (Read some of his work here and here, and listen to a podcast we did with Kostelec here.)

Warning: You may feel a powerful urge to become the Joker after reading this.

Ladies and gentlemen, without further ado:

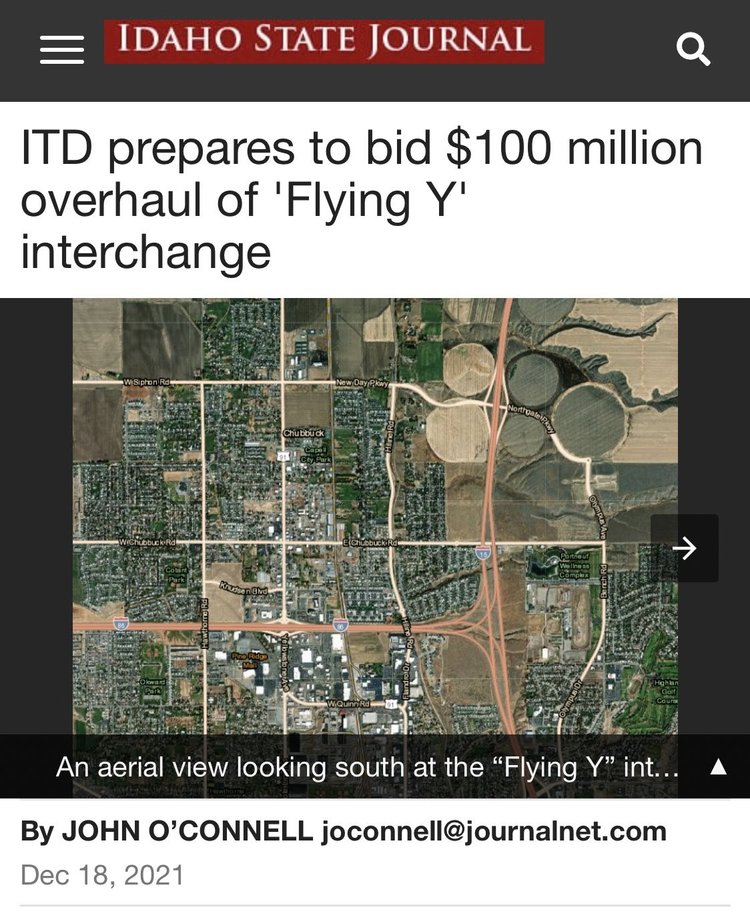

Exhibit A: $100 million is budgeted to overhaul a single freeway interchange in Pocatello.

Exhibit B: Two crosswalks near Idaho State University will get push buttons and flashing LED lights after a local Rotary club operated a concession stand at baseball games to raise the money. Oh, and a McDonald’s franchise owner chipped in some cash, too.

ITD is the Idaho Transportation Department, and like essentially every state DOT, they are steeped in 1960s assumptions that their job is to maximize the speed and flow of car traffic. Anything else appears to be secondary.

The crosswalk project was initiated by the City of Pocatello after a study identified the site (on the edge of a college campus where many students presumably walk) as a safety hazard. Because the road in question is maintained by ITD, the City applied for a grant from ITD to make the safety improvements. They did not get the grant, and turned to local philanthropy at that point.

The need to scrounge pennies to get basic safety features for people who walk is a familiar, depressing reality for anyone who has encountered the world of local transportation funding. It might not always come to the point of desperation of a beverage concession or a bake sale, but very often, these projects languish unfunded for years until some squeaky-wheel neighborhood association president or local activist manages to bring the issue up with the right public officials just enough times. (I have personally watched unpaid volunteer neighborhood advocates beg elected officials for a crosswalk as a personal favor more than once.)

Meanwhile, major road projects find their way into five-year capital improvement plans and receive federal funding out of the large and mostly-unconditional block grants given to state DOTs, whether or not there is any real local constituency demanding them, and often before locals even know anything is proposed. In the case of Pocatello’s “Flying Y” interchange, it appears ITD simply declared the project a priority and budgeted $100 million for it, although the bridges, though aging, are still in adequate condition.

It would be mistaken to assume that the issue is simply that DOT planners and officials expressly believe that drivers deserve to be lavished with attention, while walkers deserve a chance to play Real World Frogger. There’s a more insidious problem, and it’s that the system privileges certain kinds of projects—specifically, the kind with a lot of extra zeroes at the end of the price tag.

After all, a careful reader of the two Idaho State Journal articles at issue here will note that the “Flying Y” revamp actually includes the creation of a new pedestrian and cycle path. It’s not that amenities for non-drivers never get built by state DOTs. It’s that they get built when they can be tacked on to a much larger road project, padding the budget and allowing the agency to pat itself on the back for its commitment to multimodalism. (Witness this “quality of life” award given to the Utah DOT for a similar monster interchange with token multi-use path, which elicited a tremendous social media pile-on of scorn and mockery.)

The needs of non-drivers go neglected when there’s no Big Project to attach them to, just hundreds of small standalone needs. An orderly but dumb system doesn’t know what to do with hundreds of individually small needs that add up to a big need. The standard protocol—do a full project proposal, get the grant or budget request approved, assign a planner or a whole team to it, do the public engagement, solicit bids, hire a contractor, get it built—doesn’t work with small: it would paralyze the gears of the system to do that hundreds of times over.

But it’s not that the money isn’t there. It’s never been that. Southeastern Idaho could do incredible things with that $100 million for the “Flying Y,” things that would radically improve the safety, comfort, and dignity of those trying to get around outside a vehicle. But it would have to happen through a process that is far more nimble, and one that is oriented toward rapidly identifying and meeting pressing on-the-ground needs, rather than toward the idea of a checklist of big-ticket projects. That’s something that isn’t in the DNA of Idaho’s or any state’s transportation department. It’s not what they were built to do, and it’s going to take a concerted effort at every level, from local advocacy to federal pressure, to make them pivot.

In the meantime, I know we all enjoy crossing the street without fear of dying, so, uh, who’s up for a bake sale?