Editor's note: this op-ed was written in response to a recent Streetsblog article about drivers' confusion over the language surrounding automated vehicle technology. Read it here.

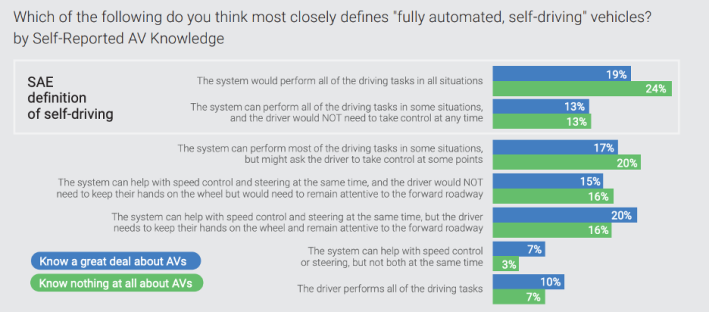

A recent J.D. Power study claimed that drivers had trouble differentiating between a “fully automated self driving vehicle” and advanced driver assistance technology. Worse, it found that drivers who thought they knew more about Automated Vehicle (AV) technology scored worse on a multiple-choice test that asked them to define the term "self-driving." The study concluded the public doesn’t really get AV terminology despite years of industry education efforts. The proposed solution: yet more education.

The real problem with this study isn’t the drivers. Rather, the team who designed the study doesn’t seem to understand the terminology they are using, as it was officially laid out by by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) in standard J3016.

In essence, the study asked a nonsense question.

Let's take a closer look at why this survey was flawed.

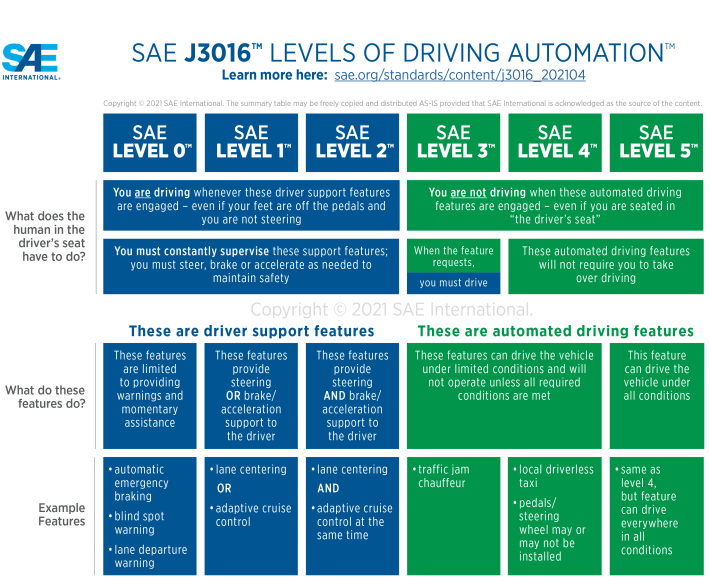

Respondents were asked to choose which of seven definitions of best matched their understanding of the term “fully automated, self-driving vehicle,” and then graded based on whether their answers corresponded to the “SAE definition of self-driving.” The answers that were deemed to be correct correspond to the definitions of SAE J3016 levels four and five (driver not responsible for vehicle driving at all). Incorrect answers roughly correspond to SAE Level 0-3 (driver participates in some or all driving tasks).

Unfortunately, the study question uses meaningless terminology that is a combination of undefined, prohibited, and explicitly incorrect, according to the very SAE J3016 standard the study references.

Let’s start with the term “self-driving.” That term is not only undefined, but is specifically prohibited by SAE J3016 section 7.1.3, because its meaning “can vary based on unstated assumptions” — and in some uses can refer to any feature level one to five.

Let's unpack that a little more. SAE levels actually refer not to vehicles themselves, but rather to vehicle features. This makes sense, because you can turn automation on and off in most vehicles. For instance, hypothetically, an car might activate a level four automated feature on highways — say, permitting its human driver to go sleep behind the wheel — but will deactivate that feature on local streets, requiring the driver to wake up and take control. Accordingly, J3016 states that there is no such thing as a self-driving “vehicle.”

Finally, in J3016 Level 4 is officially called “high driving automation” and level five is officially referred to as“full driving automation.” That terminology might seem to indicate that a car equipped with level four features is “fully automated,” but small wording differences in the source text matter. What SAE J3016 section 8.7 actually says is that calling a level four feature “fully automated” “is incorrect and should be avoided.” Based on this alone, one of the two "right" answers on the J.D. Power test — "the system can perform all of the driving tasks in some situations, and the driver would not need to take control at any time — is actually wrong.

If the survey had asked which phrase characterizes “either high or full driving automation features,” then it would have been a well formed question. But drivers would probably have had no idea what the survey was talking about, not having read – much less memorized – the very precise and somewhat obscure phrasing of the SAE engineering standard. It does not help that many (arguably most) discussions about published SAE levels get the definitions at least somewhat wrong in their attempt to simplify things. That includes a subtle but critical over-simplification of level three in the very SAE-published chart used as a source by the study.

The authors of the study involved three groups: J.D. Power, MIT Advanced Vehicle Technology Consortium (AVT), and Partners for Advanced Vehicle Education (PAVE). They represent survey expertise, technology expertise, and consumer education expertise respectively. Still, this team got the primary survey question not just a little wrong, but wrong to the point that the results are essentially meaningless.

The problem is not really the capabilities of these three organizations. Rather, if they couldn’t get it right, what hope has the average consumer?

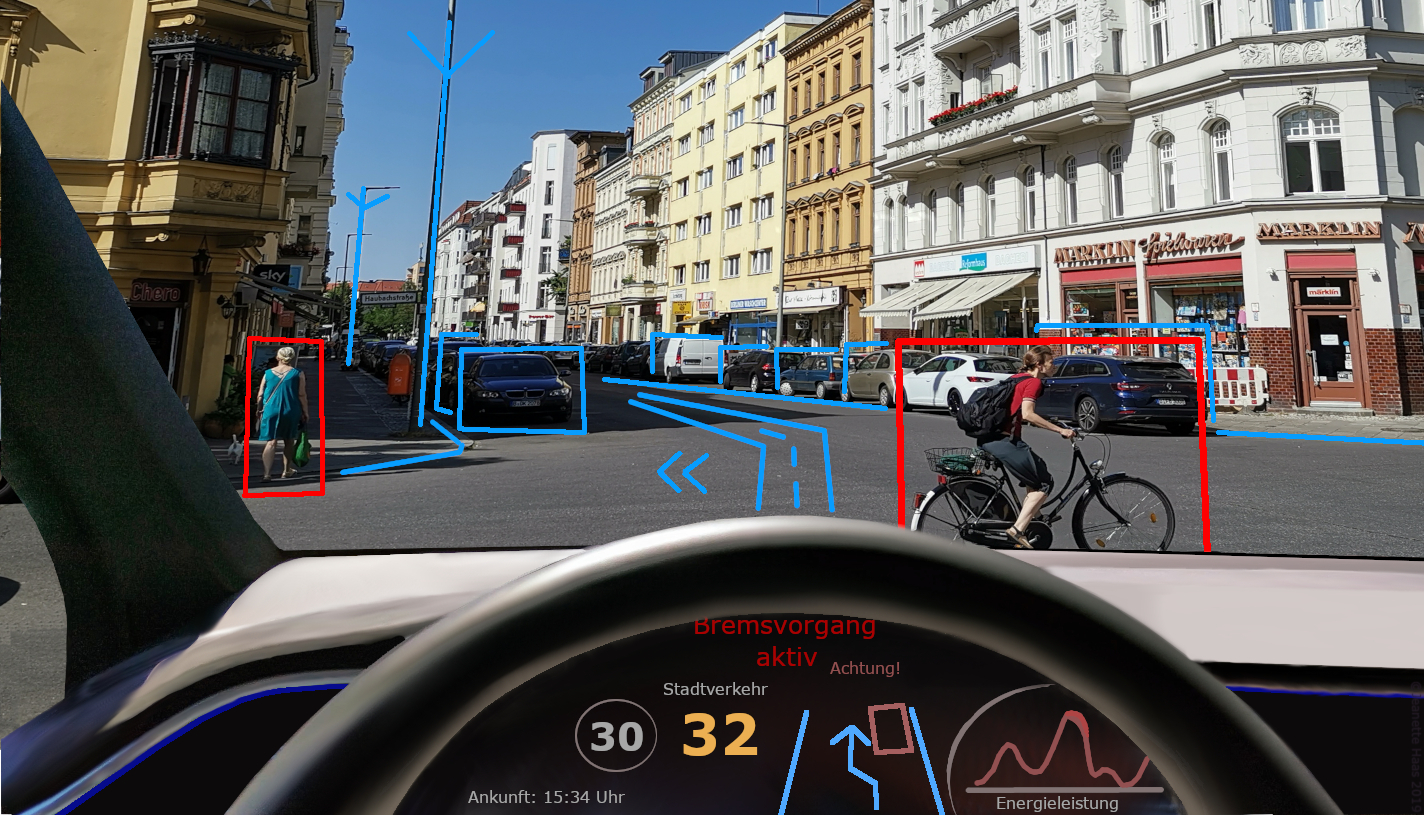

Watch this. Then picture it with rain or snow. Or just more people.

— Brent Toderian (@BrentToderian) December 14, 2021

“Full Self Driving” can’t handle cities. That’s why they want us to redesign cities to make it easier for AVs, and make us all wear sensors. https://t.co/DNS4kQysp0

Simply put, J3016 is the wrong tool for educating consumers. It’s too confusing. Worse, it has been crafted by the automotive industry to have so much ambiguity and wiggle room that it can be readily gamed. One example is the “level two loophole” by which any company testing Level 3-5 technology on public roads can try to evade regulatory oversight by simply claiming that they are only Level 2 because there is a human driver minding their test platform.

After multiple revisions and countless educational exercises, the time has come to declare the SAE J3016 Levels as hopeless for general public education. I continually interact with technologists, journalists, regulators, and others who have substantive misunderstandings about the J3016 levels. It’s time to give up – it’s not working. More education about a flawed framework won’t solve the problem. (I’ve tried to summarize the Levels myself, but couldn’t come up with anything reasonably accessible to the general public.)

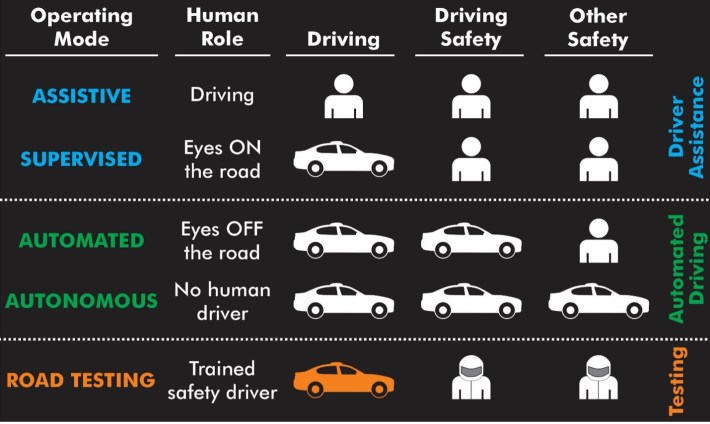

The survey report does not consider an alternative to J3016, though they do exist, including one I have proposed that is based on the user experience rather than the design of the underlying technology. My vehicle automation modes are broken down by responsibility for driving, driving safety, and other safety considerations.

A longer explanation of my methodology is available, but whether you use it as your framework or not, the bottom line is this: to successfully inform consumers about the powers and limitations of automated vehicle features, any approach we take needs to be readily apparent from a single picture. J3016 just isn’t going to get that job done.

Prof. Philip Koopman has been working on autonomous vehicle safety for over 25 years at Carnegie Mellon University.