A historic commitment to increase bike parking in Paris has U.S. advocates wondering why cycle storage doesn't get the same level of attention in American cities — and sharing policy strategies that could help.

The City of Light recently grabbed headlines with the release of its revised "Plan Velo," which leaders say will transform the French capital into a "100 percent cyclable city."

Much of the $290-million plan will be devoted to making streets safer for people on two wheels, but a significant portion will fund the construction of 130,000 new places for cyclists to store their bikes once their rides are over, including 30,000 new public racks, 40,000 new secure, enclosed spots at train stations, 50,000 new spots at private workplaces and homes subsidized by government grants and incentives, and 1,500 bike parking spots specifically for city officials.

Meanwhile, U.S. advocates struggled to compare those numbers to bike parking stats in their own cities — or to envision a future where their own leaders would make a similarly visionary commitment. (Visionary means different things in different places. New York City, for instance, hyped an announcement recently that six secure spots would come to Grand Central Station by the end of the year; those six spots represent roughly 0.006 percent of the 100,000 secure parking spaces advocates say the city needs.)

Much to love about Paris' bike plan, but check out the PARKING:

— David Zipper (@DavidZipper) October 26, 2021

➕ 30k bike corrals (with 1k for cargo bikes)

➕ 40k public bike parking spots at train stations & 50k from private sector

➖ 70k on-street car parking spots, which are being repurposedhttps://t.co/G9El9yVEaT

Even as more and more Americans wake up to the need for bike routes that keep cyclists safe from drivers, the need for safe bike storage remains under-discussed. The availability of cycle parking is sometimes, but not always, factored into the methodology that leading organizations use to rank the most bike-friendly communities in the country; cities themselves rarely track how many spots they have in any systematic way, much less assess those spots' quality, convenience, accessibility to people with mobility challenges, or effectiveness at preventing common crimes like theft.

Thanks to the paucity of good data, academics have struggled to quantify the scope of the problem — or rally governments around systemic solutions.

"When we asked cities how many bike parking spots they had, a lot of them really didn't know," said Ralph Buehler, chair of the urban affairs at Virigina Tech and one of the most prolific researchers on the topic of cycle storage. "They would say, 'We don't collect that data, but you can go in our archives down in the basement and look for yourself. Or maybe you can ask the transit agency.' I remember Minneapolis did give us a number, but it was 20 times higher than the one's we'd gathered for all other cities. When we asked why, they said, 'Well, every stop sign in the city could be used as bike parking, so we're counting those.'"

And that's not even considering the proliferation of poorly designed bike racks that make it impossible for riders to secure their bikes through a standard frame rather than a removable front wheel — never mind ones that can accommodate the flood of over-sized cargo bikes and adaptive e-cycles the impending federal e-bike credit is likely to unleash on U.S. streets.

Hey @OneNorthAvenue, I think your bike rack is in violation of #btv City Code. Time for an upgrade? #badbikerack pic.twitter.com/VRdh4AKmQG

— Liam Griffin (@liamgriffin) July 12, 2016

That haphazard approach may be keeping people off two wheels — especially in BIPOC communities.

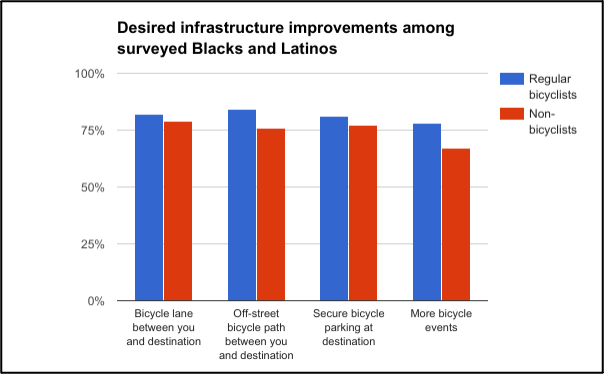

A rare 2017 survey of Black and Latinx residents of New Jersey found that bike parking was the second-most desired infrastructure improvement among both cyclists and non-cyclists, roughly on par with the desire for off-street protected cycle paths themselves. The same group identified the fear of "robbery and assault," including bike theft, as their second-largest barrier to riding.

"It’s not just that bike theft does happen, it’s that it could happen," Shabazz Stuart, CEO of Oonee, which installs secure bike parking facilities in cities around the world. "How could anyone ride to work, the grocery store, any destination, without the confidence that their bike will be there when they get back? If you can't carry your bike up the stairs to your apartment [because you have a mobility challenge, for instance], are you really going to feel confident leaving it on a rack in the street overnight? If we don't have that security, no one's gonna ride."

"There’s a fundamental blind spot that even advocates have about the need not just for any bike parking, but for secure bike parking," added Stuart. "I think that's because a lot of advocates live lifestyles where they can choose to have bike parking; they can say, 'I’m not going to move someplace where I don't have it.' But for the average person without that choice, it’s a massive barrier."

Stuart's company has garnered national attention (and more than a few StreetsblogNYC mentions for its work in and around Stuart's home) for its freestanding outdoor bike "pod" hangars and indoor "hubs," which harness on-hangar ad revenue to provide riders with free, secure storage. But Stuart says the bulk of his team's work is actually getting communities to adopt better bike storage policies city-wide, whether or not Oonee is their preferred vendor.

"What we lack, right now, is a systemic approach to bike parking," Stuart adds. "We’ve seen transit agencies adopt bike parking in the context of a park and ride, sure. But what we haven’t seen as much is cities saying, 'we have a scalable vision to put secure bike parking everywhere.'"

Stuart says some leaders in the public and private sectors are bucking that apathetic trend. Oonee recently won a citywide contract to install 29 pods across Jersey City, N.J. as part of the city's push to add 1,500 spots in five years, and his team is also partnering with private intercity rail company Brightline to install facilities at stations throughout Florida.

He says the company has also had success persuading private developers to build bike parking as part of community benefits agreements often required of new projects, which he says often saves them money compared to costlier CBA initiatives, like building new parks.

Of course, those positive policies pale in comparison to the minimum car parking standards that have dominated the U.S. for decades — though experts say minimum bike parking policies are far from impossible.

Cities like Minneapolis are already improving on their ad hoc stop-sign-bike-rack approach and requiring large developers to include dedicated cycle storage rooms, lockers, and even showers in their largest buildings, while nixing parking minimums for automobiles. And as cycling gains in popularity, even bigger storage solutions are possible.

"In the U.S., the proliferation of cars created a problem: they were littering the streets," Buehler adds. "But in places like Amsterdam, biking is so popular that the public perceives parking your bike outside as littering — which is why they built their massive bike garages."

Amsterdam isn't the only city whose bike parking facilities Buehler has studied — and it's model isn't the only one that gets people riding. He points out that cities like Copenhagen, Denmark often forgo enclosed storage in favor of self-locking bikes in designated outdoor corrals, while in Tokyo, Japan parking bikes outside is typically illegal, which has made pay-per-use indoor bike storage a common feature of city streets and businesses.

But throughout the world, Buehler says studies have shown "that the presence of (safe) bicycle parking increases the likelihood of commuting by bicycle" — no matter what form it takes.

Which model will come to dominate American cities remains to be seen. But with relatively expensive electric bikes surging in popularity, most advocates expect bike parking and bike charging to rise to the forefront of the discourse soon.

"It's pretty unbelievable to see these fancy e-bikes floating down the street in a rainstorm," laughs Stuart. "Parking is so important for cars that it dominates almost every land use conversation. But we expect biking to be a serious mode of transportation without giving bike storage the same attention. I think it represents a big question: are we going to treat cycling as a real way of getting around, or will it still be seen as a form of recreation?"