Even the most transit-poor U.S. cities have significant numbers of neighborhoods where almost no one drives, new research suggests — and where such neighborhoods are located often suggests a dire need for more transit to serve the under-resourced residents who need it most.

Retired geographer, librarian, and writer Chris Winters recently posted on his blog, Liberal Landscape, an analysis of census data that located the tracts with the highest concentrations of households living without cars. Nationally, only 8.7 percent of American families are automobile-free, and in large swaths of the country, virtually every household owns a private vehicle — if not two or more.

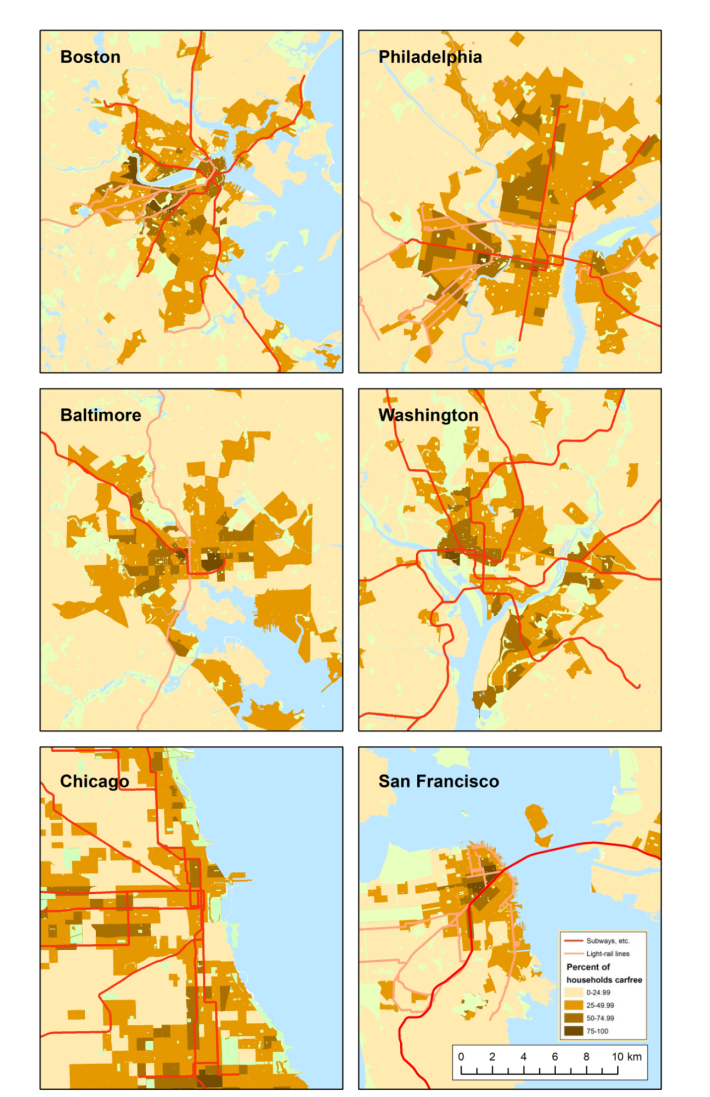

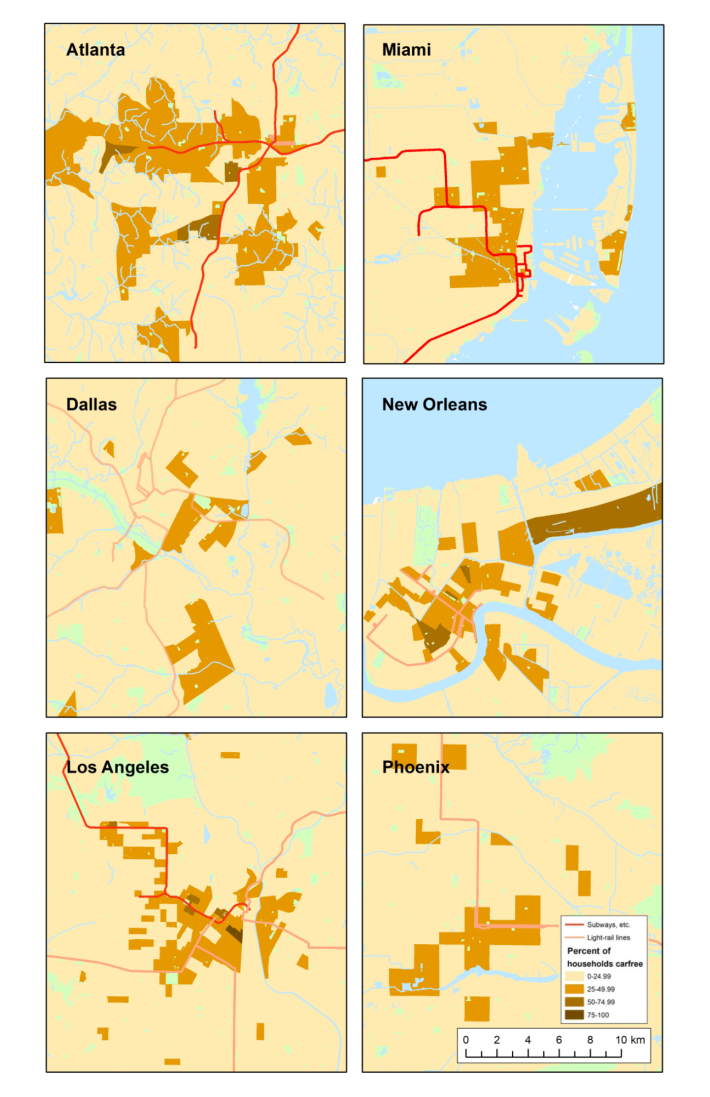

But in almost every major U.S. city, Winters did find at least some neighborhoods where private vehicles aren't the primary mode of transportation. In a whopping 1,660 census tracts, more than 5o percent of occupied households were carless — including in some of the most notoriously car-dependent metros in the U.S., like Cincinnati, Ohio, Detroit, Mich., and St. Louis, Mo.

As a geographer, Winters didn't analyze what the country's car-light neighborhoods have in common, but advocates who responded to his post were quick to point out some similarities. In general, tracts with light rail lines tended to have higher concentrations of households without automobiles, though in some cities, like Baltimore, some of the most heavily transit-dependent areas weren't being served by rail at all — consistent with recent research that shows that local transportation leaders are failing to prioritize convenient shared options for the Charm City residents who need them most.

In other communities, car-light neighborhoods were more heavily associated with concentrated poverty than robust transit investment. The map of significantly-less-car-dependent neighborhoods in St. Louis, for instance, is nearly identical with the map of census tracts with high numbers of low-income residents; the only relatively car-free neighborhood located directly along the city's light rail network, meanwhile, is the site of a large residential university.

That tracks with decades of criticism from local advocates who say leaders have failed to prioritize connecting the Gateway City's heavily Black and low-income north side with its wealthier, whiter south side and its job centers, despite a deep need for shared transportation options in the poorer half of the city.

"It’s an argument for increasing public transit, obviously," said Winters. "Even if fewer people are taking it during the pandemic, there are still lots of folks who really are transit-dependent, and they come in all income classes and across all geographies.

Winters acknowledges that truly auto-light havens are still few and far between in the United States, noting that there are only 350 census tracts across America where more than 75 percent of households are living without a car — and the vast majority of them (312) are located in his transit-rich New York City. (He was surprised by how many residents of relatively car-dependent Staten Island were making do without a private automobile.)

Still, Winters says it's important to remember that there are people who don't, can't, or can't afford to drive in every U.S. neighborhood — and that even the most car-dependent communities likely have more demand for transit than their leaders are answering, and not always in the neighborhoods they might assume.

"Car addiction is pretty universal in the U.S.," said Winters. "It's something we really need to contend with."