Birmingham grabbed headlines this week for its visionary new transport plan that will restrict car travel and expand sustainable transportation access throughout every inch of the city, cementing their status as a world-class city and Vision Zero leader.

Alas, not that Birmingham.

For the last week, a spate of glowing articles from both sides of the pond have been celebrating the news that the City Council of the northern England metropolis is primed to pass a new transport plan that explicitly promises to reduce "reliance on cars, [which] will also serve to reduce the demand for car parking, releasing land for more productive use — for example, new homes and new employment sites."

That caused confusion among U.S. sustainable transportation advocates, who initially thought journalists were talking about the second-most-populous city in Alabama — and more than a little disappointment when they realized that no U.S. city is planning anything near this ambitious for their roads and railways.

Was hoping this was Alabama, I'd be more surprised.

— John Klein (@JohnKleinRegina) October 4, 2021

Of course, the City of a Thousand Trades isn't strictly comparable to the Magic City — even if both have deep roots in the automotive industry.

The English metropolis has a population of 1.1 million (or a whopping 3.6 million, if you include the larger metropolitan area), making it the second largest urban center in the United Kingdom and one of the crown jewels of a country whose national transportation code was revised this summer to explicitly put pedestrians at the top of the road user hierarchy.

Birmingham, Ala., by contrast, has a population of 212,000, and (or 1.1 million in the metropolitan statistical area) — less than one-fifth of the English city, despite being roughly half its geographic size — and is ranked in the top 20 most dangerous cities in the country for people on foot, in a state that's the second most dangerous in the U.S. for walkers overall. Those terrifying stats no doubt have a lot to do with state and federal leadership that privileges the movement of automobiles over the safety and dignity of other modes, despite the best efforts of cash-strapped local advocates.

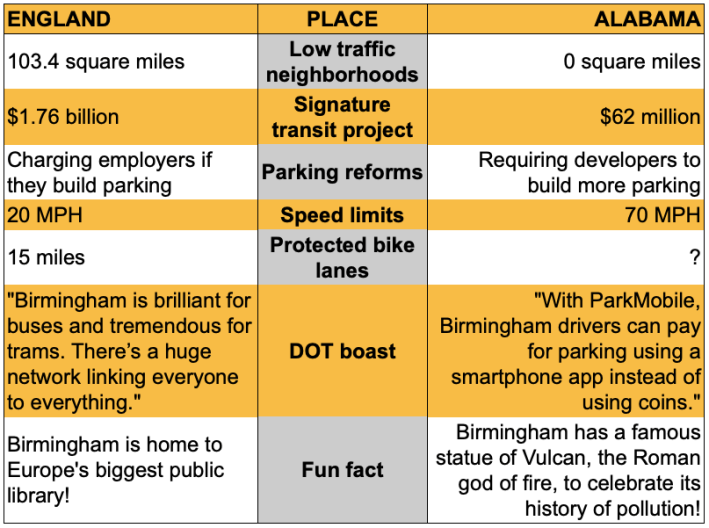

Still, it's pretty eye-opening to compare the two Birminghams' very different progress towards their transportation futures — especially considering that most U.S. cities wouldn't stack up much better against the Brits than their colleagues in Alabama. Here are a few notable points of comparison (with a handy "Tale of the Tape" like we used to do in the days of print newspapers):

Low traffic neighborhoods

Probably the buzziest aspect of the plan for Birmingham (England) is a scheme to transform the entire city into a series of massive low-traffic neighborhoods. By restricting the majority of motor vehicle traffic to the ring road encircling the whole community and only allowing motorists to enter the city core via a handful of roads running between seven core zones — with exceptions made for local residents and people with disabilities — traffic engineers will essentially give almost every street back to people on foot, bike and transit, all at once.

My @guardian article now has a graphic showing how Birmingham will soon become one big low-traffic neighbourhood. And goal is to massively reduce motoring far into the suburbs, too. https://t.co/TWw7CGKYXV pic.twitter.com/d1ezi8NKKB

— Carlton Reid (@carltonreid) October 4, 2021

Streetsblog could not find evidence that Birmingham (Alabama) has anything like a low-traffic neighborhood within its borders, though it does allow residents to apply for limited traffic-calming dollars. Proposed projects are judged based on "recognized feasibility indicators" like vehicle speeds, crash statistics, "context" and more. (Translation: safe roads will always be the exception, not the rule.)

Signature transit projects

Across the Atlantic, Brummies are about to get a major expansion to their West Midlands Metro light rail network, whose planned extensions will roughly "triple in size over the coming years" thanks to a massive £1.3-billion ($1.76-billion) investment in the mode. Midlands already has an average annual ridership of eight million, or roughly eight trips per resident per year. A further 259 million trips were made on the local bus network from 2017 to 2018, or an impressive 25 trips per resident — but the report authors despaired of this number as a seven million-ride decrease over the previous year, which signals an urgent need to invest more in shared modes. (U.S. transit leaders, meanwhile, are frequently forced to slash funding when ridership ebbs.)

Birmingham-Jefferson County (Alabama) doesn't have a light rail system, but its residents do rely heavily on its bus network: the system averages about three million rides a year, or roughly 14 trips per resident, which isn't particularly surprising considering that 13.7 percent of city households don't have access to a car. (That's more than twice the U.S. average, though less than half of the rate in Birmingham (England) of zero-vehicle residents: 38.5 percent.)

But the Alabama city's signature transit project is a considerably more modest than its English counterpart's. The Birmingham Xpress bus rapid transit line — the first in state history — will connect 10 miles of Birmingham at an estimated cost of $44 million, plus $18 million in COVID-induced overages that the city recently announced will be covered out of American Rescue Plan Funds.

That's certainly nothing to sneeze at, but it's still a harsh reality check to compare the near-term transit goals in the other Birmingham — holistic, multi-billion "improvements and extensions to bus, bus rapid transit, train and tram networks including prioritization over private car travel" — to that of Birmingham (Alabama): a single bus rapid transit line that's long overdue.

Parking reforms

The Brits' plan is aggressive in its approach to curbing excess parking, which the report authors recognize is a key strategy to eliminate car dominance. Under the plan, parking will "be used as a means to manage demand for travel by car through availability, pricing and restrictions," like a new workplace tax levy "under which employers are charged an annual fee for each workplace parking space they provide," with all funds redirected to specific transit, biking and walking improvements.

Parking will also be slashed around schools, "in areas which are well served by public transport" like the city center, and all spaces that remain will be prioritized for the use of "people with disabilities, cyclists, car clubs [Ed. note: car-sharing services, in U.S.-speak] and other sustainable modes."

On top of all that, council-owned car parks will also be converted into badly-needed new housing — something it's hard to imagine a U.S. city willingly doing.

Birmingham (Alabama), meanwhile, still imposes mandatory parking minimums on virtually all new developments.

Speed limits

On the handful of roads where Brummie drivers will be allowed to travel, they'll still be forced to hit the brakes: the plan will cap the default speed limit for all residential areas at 20 mph. (A speed which, as the saying goes, is still plenty.)

Birmingham (Alabama), by contrast, is crisscrossed by a half dozen interstates with maximum speed limits of 70 miles per hour, and a massive number of arterials and state-owned highways. Even in residential areas where pedestrians are allowed, max speed limits are still 25 miles per hour — a small difference that substantially increases a pedestrian's risk of dying in a crash, especially for older walkers — while county roads can be legally signed at 45 miles per hour.

Separated bike paths

Birmingham (England) is already home to a respectable 15 miles of segregated cycle routes and a significant number of cycling-safe calm streets, thanks to the city's robust "Cycle Revolution" program — and the Transport Plan aims to add even more.

Officials are also considering re-routing the A38 tunnel to the ring road, possibly opening that thoroughfare to cyclists and pedestrians exclusively.

Birmingham, England will reallocate its central city tunnel to "green spaces as well as cycling and walking" instead of cars. Not clear if it was considered to use it for trains or buses.

— Cap'n Transit (@capntransit) October 6, 2021

The NYC DOT is currently planning to rebuild the Trans-Manhattan Expressway as is. https://t.co/1L18ZWSNds

Despite our best efforts to dig around the 216-page bicycle master plan for Birmingham (Alabama), Streetsblog couldn't find solid evidence that the city has any segregated cycle paths, give or take a few rail trails and short paths outside the core downtown that are not oriented towards transportation cyclists.

The dearth of federal subsidies for active transportation networks probably has something to do with that — though if Washington realizes just how far behind the ball U.S. cities are compared to their European counterparts, maybe that could change soon.