President Biden says he's taking action to cool deadly urban heat islands — which are located disproportionately in communities of color — but advocates say he isn't doing enough to address one of the phenomenon's biggest root causes: America's overbuilt, auto-centric road network.

Following a summer that broke heat records last set during the Dust Bowl, the White House announced on Monday the launch of an interagency effort aimed "to respond to extreme heat that threatens the lives and livelihoods of Americans."

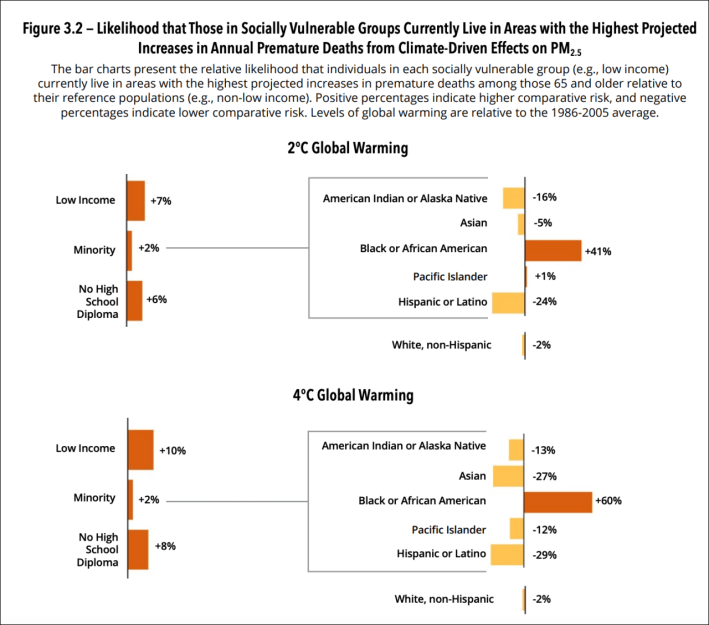

Those threats aren't distributed equally. A damning new Environmental Protection Agency report recently found that as climate change gets worse, Black and African-American residents are 43 percent more likely than Whites to live in neighborhoods projected to experience annual increases of up to 187 additional premature deaths per 100,000 residents, mostly due to heat stroke, asthma, and other heat and pollution-related health conditions.

Scientists agree that two of the largest drivers of urban heat island effects are excessive use asphalt — like parking lots and wide, car-focused roads deliberately denuded of cooling infrastructure like trees on behalf of drivers — and excessive waste heat from vehicles themselves.

"The heat emanating from cars every day contributes to a vicious cycle: as the city gets hotter, building air conditioners work harder, pumping even more heat outdoors, and the pavement of parking lots and highways retains all that warmth for hours after the sun goes down," Streetsblog MASS reported earlier this year about waste heat's effect on Boston. "Even electric cars end up converting kinetic energy into waste heat as they move about a city, and their drivers will still demand vast, sun-baked plains of asphalt to drive and park on."

But the White House failed to explicitly name autocentricity as one of the most critical drivers of the national heat island epidemic — and the strategies Biden proposed to beat the heat largely fail to decenter the automobile in any meaningful way.

Among those initiatives were new guidelines for cities seeking to plant urban forests, a new interagency working group that will facilitate new data-sharing efforts around the problem, and even a new federal competition to find new "new ways to protect people at risk of heat-related illness or death during extreme heat."

But the list conspicuously omitted powerful (and proven) mitigation strategies that inconvenience drivers, like taking steps to reduce vehicle miles traveled — and it didn't announce any new initiatives to give communities and their residents more money to implement the solutions it was recommending, either. Even the most ambitious city greening initiatives, for instance, are likely to fail without robust investment, as researchers in Pittsburgh found in a recent study. Forestry Department officials revealed that while 74 percent of residents support expanding the tree canopy, only 17 percent of department funds actually went to planting new trees — a rate that was barely sufficient to replace trees that had recently died.

on top of removing space for cars in cities, we also need to invest heavily in blue-green streets. #SpongeCityhttps://t.co/K37IlcldAQ pic.twitter.com/jj37zF3RoU

— Mike Eliason (@holz_bau) August 25, 2021

Of course, toothless guidelines and federal clearinghouses can only do so much to restructure the way U.S. communities are built — especially considering how legislation like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, which would provide a historic $110 billion in federal funds for new roads over five years, might incentivize cities to undercut all these efforts to cool America's urban cores.

Until the federal government takes radical action to finally stop pouring taxpayer dollars into the creation of new urban heat islands, local efforts to mitigate the ones they've already got may be a losing battle — and vulnerable road users will be the ones left out to fry.