School bus driver shortages during the pandemic are crippling the single largest segment of the U.S. public transportation fleet and forcing districts to pay parents to drive their kids to class instead — and the U.S. may not be able to fill the gaps until these essential workers are finally given the wages, benefits and protections they've long deserved, advocates say.

Countless U.S. parents were welcomed to the new school year with the decidedly unwelcome news that the yellow buses they rely on wouldn't be arriving, thanks to a surge in resignations and retirements among pandemic-beleaguered bus drivers. Experts say the industry has struggled to hire and retain drivers for years, thanks in part to stagnant wages and benefits from cash-strapped districts and the private motorcoach companies with which about 40 percent of schools have opted to contract, but the added dangers of the COVID-19 pandemic have accelerated the shortage into a full-blown crisis — and as more school commute shifts into private automobiles, families with children won't be the only ones paying the price.

Schools in Wilmington and Baltimore made headlines last week with the news that they would pay families taxpayer-funded stipends of as much as $700 for the year or $250 a month to forgo the yellow bus and transport their kids to school instead — a program that advocates fear will tempt some parents and guardians in those largely car-dependent cities to drive even more than they already do, while leaving students from car-free families stranded with nothing. (About half of U.S. school kids take the bus to school, though 60 percent of students from low-income families do, in large part because they're significantly more likely to live in households without private automobiles.)

The EPA estimates that school transportation in low-occupancy cars already accounts for as much as 30 percent of U.S. rush hour congestion, which also means more emissions, traffic violence, and increases to the other negative externalities of driving — for all of us.

Impossible choices

Districts that can't or won't pay those sorts of road-clogging incentives, meanwhile, are struggling to find good alternatives.

Educators in Pittsburgh recently announced that they would be forced to postpone the entire school year by a full two weeks to give operators more time to find drivers and complete the 17- to 22-day hiring process necessary to secure them commercial licenses and rigorous background checks. In Granite City, Ill., students were preemptively excused if they couldn't reach the classroom on the region's thin local transit system, for which the district was forced to purchase them student passes upon request. Families in transit-poor communities like Stillwater, Minn., meanwhile, were given no choice but to wait for the handful of buses that were still running, often arriving to class hours late; the district recently filed a breach of contract lawsuit against the operator responsible for the routes.

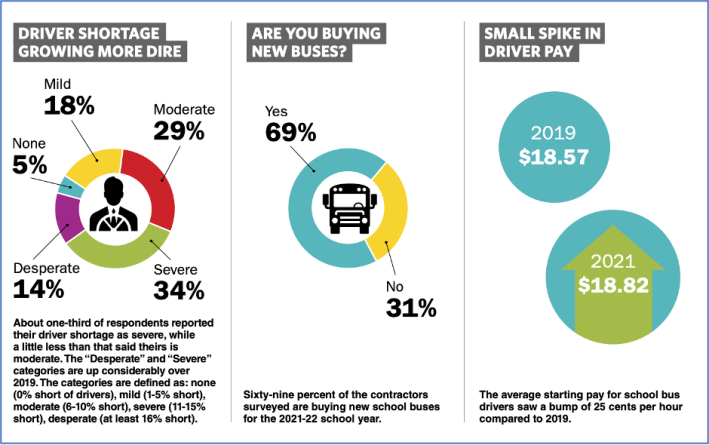

Those sorts of grim headlines aren't just anecdotal. A recent survey from the National Association for Pupil Transportation found that between 83 and 91 percent of school transportation providers had been forced to adjust service levels, depending on the age of the students they transported, with elementary schoolers — the vast majority of whom are not old enough to be vaccinated against COVID-19 — experiencing the largest share of the disruption.

A whopping 51 percent of respondents classified their region's hiring woes as either "severe" or "desperate."

'A perfect storm'

Even if the hiring crisis is particularly dire now, experts emphasize that the pandemic merely raised the stakes of the school bus industry's flawed labor model, rather than creating the problem — and that worker's demands are fundamentally the same as they've always been.

Long before the pandemic made transportation sector employees the profession with the second-highest rate of COVID-19 deaths, workers in the school transportation industry were subject to grueling split-shift schedules that started as early as 5:30 in the morning and sometimes didn't end until the last whistle blew on after-school sports practices, keeping drivers away from home for 12 or 13 hour days without earning them enough continuous hours to qualify for full-time benefits. When increasing privatization in the industry resulted in slashed wages, that notoriously difficult job became even less attractive to new recruits.

"COVID definitely made things worse, but our shortage started when Mayor Bloomberg bid out our work and traded away almost all the job protections that we'd had for over 40 years," said Michael Cordiello, leader of the Local 1181 NYC School Bus Union. "And what did that do? When these private companies come in, well, they want to make a profit. A bus costs the same no matter where you buy it; insurance, gas, it's pretty much same thing. Guess where you save money? It's on labor. Wages got cut in half from an average of $26 to $13, and people lost their benefits and their pensions practically overnight."

The hiring pool contracted even further when schools went virtual, furloughing thousands of drivers and often leaving the few who remained with inadequate personal protective equipment to keep themselves safe, much less hazard pay to compensate them for their heroic efforts to keep the wheels on the bus going round and round. Despite advocates' valiant attempt to sway Congress, the private motorcoach industry was largely cut out of federal COVID relief funding like the American Rescue Plan, and the school districts that did keep their bus fleets in-house didn't always pass those funds on to drivers.

Between 2020 and 2021, the average starting pay across the industry rose from $18.57 to just $18.82 an hour — 25 cents per hour, or slightly less than the rate of inflation.

Unsurprisingly, workers didn't exactly jump at the opportunity to risk their lives for a couple extra dollars a day. The Amalgamated Transit Union reports that prior to the pandemic, the New York City school system could reasonably expect about three times as many new drivers to fill the slots of recent retirees, which mathed out to 277 retirements and 800 new recruits in 2019 alone — not enough to cover that year's shortages, but far better than what was in store for the industry during the COVID era. In 2020, another 253 retired, but only 405 new drivers were hired; in 2021 so far, the ratio is just 244 to 220.

"It's a perfect storm," added John Costa, International President for the Amalgamated Transit Union. "The ATU has had 160 members die so far due to COVID that we know of. A lot of these [hiring] shortages have to do with people deciding not to come back and do this type of work due to the safety concerns, but that's not the only problem here."

Costa says that to solve the shortage for good, it's critical that districts and private operators start treating drivers as the professional front-line workers they are — and give them protections to match.

"These are hard, full-time jobs, and workers need decent benefits, a pension that makes sense, and a fair wage, period," adds Costa. "You can stand around offering new drivers $5,000 bonuses all day, but that's just insulting to the people who have been there a long time who are getting nothing — and eventually, those new drivers are gonna want more basic protection, too...Unless the industry changes their way of thinking and recognizes that this isn't just a part-time job for retirees anymore, and it needs to be treated as full time career with benefits, they'll never get out of this."

Until that happens, the least schools can do is organize more ways for parents to get their kids to school safely — ideally, without a car at all.