As Washington celebrates a bipartisan infrastructure agreement, advocates are still wondering what, exactly, the bill will actually build — and whether the incessant chatter about pay-fors and intra-party compromise is eclipsing a more critical dialogue about how urgently American transportation policy needs to be reformed.

On Thursday afternoon, President Biden announced that he would throw his support behind the so-called Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework, which would inject $1.2 trillion into a range of mostly transport-related infrastructure priorities across eight years, paid for by a "couch cushion" scrounge mostly from existing programs. But save a list of big dollar amounts promised to vague top-line categories — e.g. $11 billion for "safety," which could mean anything from protected multimodal infrastructure to even more of the same pedestrian-blaming educational campaigns — the White House has not yet released the details of which priorities from Biden's original stimulus bid, the American Jobs Plan, survived negotiations with centrist lawmakers from both sides of the aisle.

Or to put it more simply: American taxpayers have no idea yet what their $1.2 trillion will actually buy —and whether the centrist vision will merely further enshrine car culture and all its violent impacts upon American lives.

That troublingly uncertain news comes as Washington continues an equally frustrating debate around the surface transportation reauthorization — yes, another massive infrastructure bill — that could also help radically reshape the way U.S. residents get around...or maintain the autocentric status quo.

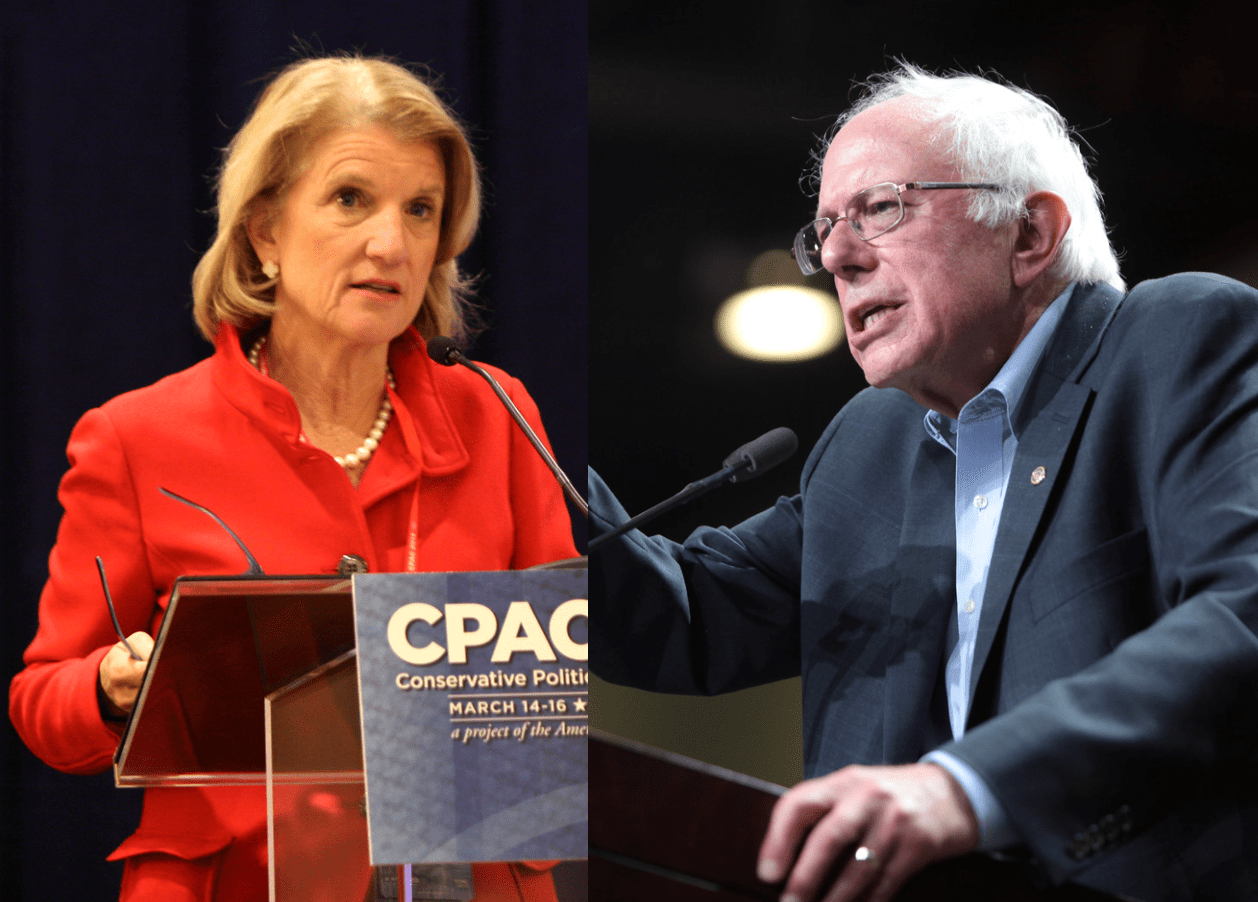

But as committees in the House and the Senate frenziedly mark up some of the most consequential transport legislation in a generation, much of the public debate on the impending laws has been less about the actual substance of our transportation future than who will pay for it all. Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W. Va.) set off a flurry of thinkpieces when she drew a "non-negotiable red line" around raising corporate taxes to pay for transportation spending; soon after, Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.) drew his own line in the sand around raising gas taxes and instituting new fees for electric vehicle drivers, which are the GOP's and centrist Democrats' funding methods of choice.

As lawmakers spar, advocates fear that Washington is missing the forest for the trees — and throwing away one of the best chances in modern history to set a bold new vision for transportation.

"I am not comforted by the notion that big corporations will pay for transportation programs that will divide Black and brown communities," said Beth Osborne, executive director of Transportation for America. "I mean, the way we talk about this stuff is a little like we're trying to invest $100,000 into updating a home to get it ready to sell. If we build a spectacular new bathroom, great — but if we do that and the electric isn’t up to code and the roof is falling in, that’s obviously not a good investment. But, hey, at least jobs were created! [Laughs.] Particularly in the Senate these days —but it’s really been Congress traditionally — their focus has been on making it rain. My focus is on making communities better places to live and getting people access to opportunity."

Osborne isn't surprised that partisan bickering over pay-fors has drowned out the conversation about how to reimagine infrastructure policy for the 21st century. Since surface transportation reauthorization only happens roughly once every five years — and infrastructure stimulus only once in a blue moon — few lawmakers employ more than a handful of staffers dedicated specifically to understanding transportation policy at a deep level. And for longstanding members of the Congress, memories of the days before the Highway Trust Fund went bankrupt in 2008 are still fresh, which does not always prepare them for a modern dialogue about right-sizing the country's road networks or adapting funding mechanisms for an era of accelerating climate change.

"We have not had a legit conversation about how to raise new money for transportation since Reagan," said Osborne, referring to the last time the federal gas tax was raised during the reauthorization process in 1982; the most recent increase was approved during a budget debate way back in 1993. "The conversation we’ve had ever since then is, 'Well, we’ve got all this money; how do we split it up?' But that's not the conversation anymore; we have a deficit. [A lot of lawmakers] don’t get how to navigate that, because they've never had to do it before."

Not every infrastructure bill under consideration is so divorced from modern transportation realities. Osborne is particularly optimistic about the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee's INVEST in America Act, which makes historic commitments to transit, biking, and walking while requiring states to fix highway infrastructure first before they build new roads, among a raft of other overdue safety, climate and equity reforms.

"The INVEST Act stops perpetuating the problems it’s otherwise trying to improve," said Osborne. "I really like that approach to policymaking. What we’ve done in the past is say, ‘Oh, the roads are so dangerous for bicyclists and pedestrians! Here’s a billion dollars a year to fix it — and meanwhile, we'll spend $40 billion a year making even more dangerous roads for bicyclists and pedestrians, while letting states set safety targets where more people die.' And everyone seems to think that that’s a great bipartisan win."

Osborne hopes that the INVEST Act can build the advocate support it needs to make its way into law. But it will take a lot of education for the American public at large to learn to cut through the noise about pay-fors and vague, top-line spending numbers, and start actually imagining everything their transportation landscape could be.

"The American people have been told, 'hey, no matter where you move, no matter what you need to do, we will give you a system whereby you can get in the car alone at the same time as everybody else in your community does to, and you won’t have to slow down at all — and it won’t cost you any more money,'" said Osborne. "That was just a lie. Anyone logical always knew it was a lie. But we’ve been telling people that for more than 65 years."